For some time now, various forces have been pushing us away from using paper money to pay for things. That goal may have a hidden bonus: Cash, it turns out, is crawling with bacteria.

Although researchers have known for some time that microbes can, and do, live on money, a new study from Hong Kong shows that these bacterial communities are more substantial than previously suspected. Cash, it turns out, could be an excellent way to monitor the microbes circulating through a city.

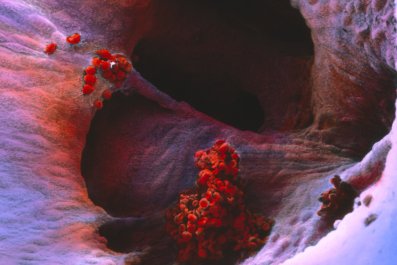

To examine the extent to which bacteria live on money, researchers from the University of Hong Kong collected 15 paper bills from cashiers at 12 hospitals and three metro stations (the underground transportation system) across that city. Their first step was to check whether microbes could survive on the bills. To do this, they scraped bacteria from the cash and placed them in various cell cultures—petri dishes containing different types of agar, a substance derived from algae that serves as a growth medium. The results, published in Frontiers in Microbiology, showed that the bacteria grew readily, indicating that they were living on the money.

Related: Is IBS all in your mind? New research on the gut-brain connection

The most common bacterial strain on the Hong Kong bills was Propionibacterium acnes, which is linked to skin acne. One type of P. acnes found on currency was first isolated from a patient with sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease, in 2013. Among the 15 sample bills, about 36 percent of the bacteria were pathogenic, meaning capable of infecting humans. The infections caused by those bacteria are not necessarily dangerous. But the finding emphasizes the fact that money is most definitely a vehicle for potentially contagious microbes.

Also common among the samples was a bacterium called Acinebacter. This category includes a range of species mainly found in soil and water, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All known Acinebacter species can cause human infections, but most such infections are caused by one called Acinebacter baumannii. Healthy people are usually not affected by A. baumannii, but the bacteria can cause pneumonia or wound infections in people with weak immune systems, chronic lung disease or diabetes.

Related: Antibiotic-resistant infections spiking in children

The study found no difference in the bacterial communities present on bills that came from hospitals compared with those that came from metro stations. That finding was important because it indicates that microbes circulate widely through a geographic region. The study authors theorize that money "serves as a kind of fingerprint of the city's microbiome."

The researchers found more bacterial species among the Hong Kong bills than other studies have found in samples taken from people's palms, the air inside metro stations, drinking water and seawater from the area. The researchers also found more antibiotic-resistant genes among the money bacteria, compared with the other populations.

This new study joins a growing field of research seeking to keep track of bacterial communities in cities. Scientists are trying to find the most reliable places to look for potentially dangerous pathogens emerging across the world. Wastewater, doorknobs and other surfaces and substances we have frequent contact with may all serve as such "alert systems," says Andreas Voss, a microbiologist who teaches infection control at the Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands. Voss, who was not involved with this study, thinks wastewater is probably the most accurate source for microbe monitoring, especially if it can be traced to its origin point, be that a farm, a home or a public toilet.

Voss notes that the ability of bacteria to grow on money depends on several factors, including what the money is made of (U.S. dollars and euros are not made of the same material, for example), the geography of the region (coastal environments and humid climates may be more conducive than drier, inland places) and sanitation. That assertion is supported by the study: The Hong Kong researchers found more marine bacteria on their samples than another study found on bills in central India, far from the ocean.

Can we catch infections by handling money? Voss considers the chances of acquiring a disease from contact with paper bills to be negligible, "most certainly when people adhere to basic hygiene principles." But, the study authors write, the new findings "unveiled the capabilities of this common medium of exchange to accommodate various bacteria, and transmit pathogens and antibiotic resistance." In other words, paper bills may not pose a widespread health threat, but they could.

Bacteria resistant to antibiotics are a global threat. And high-density cities are susceptible to outbreaks because of the close proximity of their residents. Several infectious diseases have plowed through Hong Kong in the past few years, including avian flu, SARS and swine flu. So creating effective methods for monitoring bacterial communities is critical. If the findings of this study are any indication, we may not want to rush to give up our paper money as long as we wash our hands after use.