Planet formation is a messy business, marked by swirling clouds of dust, a hail of comets and asteroids, and giant collisions. But scientists had thought that the sinking of heavy iron to the Earth's core—and the accompanying rise of lighter rocks to the surface—was a fairly tame affair. As it turns out, new evidence suggests the process was much more exciting. And the findings raise intriguing questions about the Earth's formation.

To better understand how the young Earth formed, researchers at the Smithsonian Institution and the Carnegie Institution, both in Washington, D.C., turned to a device called a diamond anvil cell, which can mimic the super high temperatures and pressures found in early Earth, albeit on tiny samples.

Diamond anvil cell in hand, the geologists looked at how radioactive iodine decays under different conditions. They found that the only way to match what we see on Earth today is if some clumps remained in the mixture, with early Earth never getting completely stirred together. In other words, the early years of our planet were a time of chaotic upheaval, not peaceful settlement.

"Our findings suggest that as the core was extracted from the mantle, the mantle never fully mixed," co-author Colin Jackson, a geologist at the Carnegie Institute of Washington, said in a press release. A new paper describing the study is published in the journal Nature.

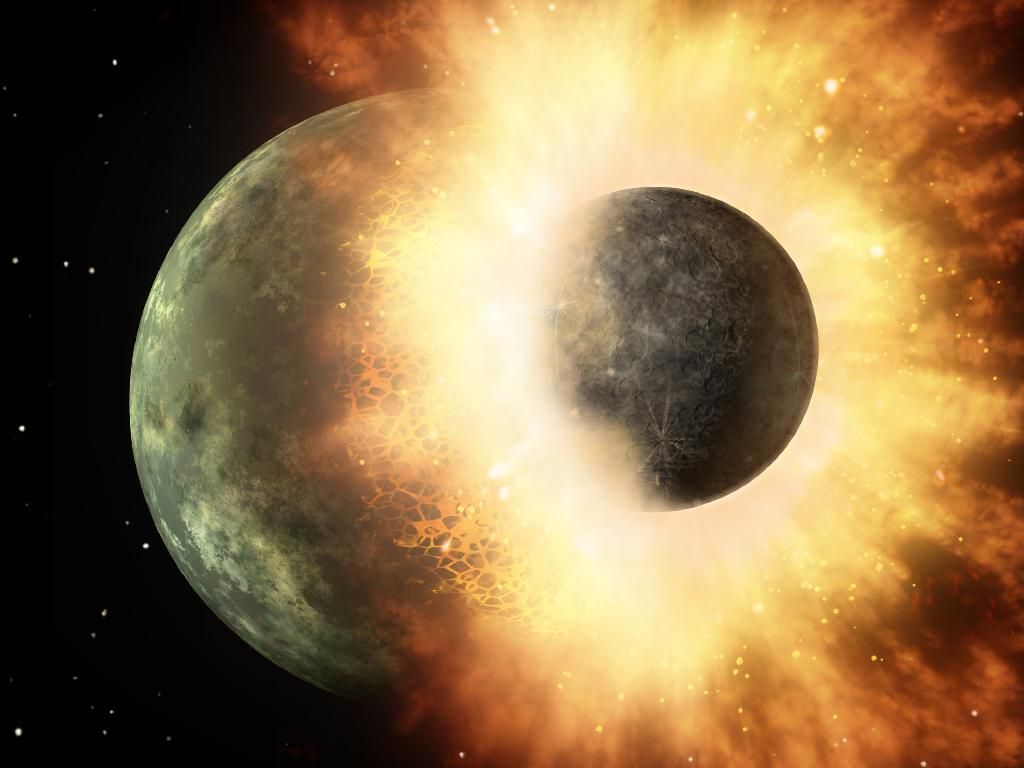

The results surprised the team. When these layers were starting to settle out, the young Earth was still recovering from a gigantic hunk of rock plowing into it, which had always seemed like the sort of thing that would mix things up pretty thoroughly. "It was widely thought that these very energetic impacts would have completely stirred the mantle, mixing all of its components into a uniform state," Jackson added.

Read more: How Does Life Start? Meteorites Have Brought Ingredients of DNA to Earth

That incomplete mixing left dense chunks in the mantle, where the chemical fingerprint is a little different from both the mantle and the core. "Like chocolate chips in cookie batter, these dense pockets of the mantle would be very difficult stir back in," Jackson said in the statement. That's the only way to match the same chemical signatures they found in modern samples.

And we see those signatures today. Plumes stretching from deep below the ground up to the hot spots that lie beneath volcanoes—like the one that has formed the Hawaiian island chain over millions of years—are reminders of our planet's early, (even) more chaotic years.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.