China has long been involved with independent Africa for at least 60 years, since first establishing diplomatic relations with Egypt in 1956. Its help for liberation movements, including Robert Mugabe's in Zimbabwe, and its building of roads and railways are features of a curious international cooperation. This can have clumsy moments, such as the behavior of private Chinese mine operators in Zambia, whose lack of concern for their workers' health and safety is causing political tensions to rise ahead of that country's August elections.

Nevertheless, the generosity of Chinese aid and the size of foreign direct investment has led African governments to excuse, work around, or simply accept Chinese excesses. But in 2015, with the Chinese economy slowing down, the volume of trade between the two continents has sharply dropped. China's Customs Office reported that African exports to China fell by 40 percent in 2015. The slowing Chinese industrial machine did not need as much petroleum and other raw material inputs as anticipated.

For Africa, for whom China has become the largest trading partner, this is bad news. For those countries, like Zambia, where China is both a key trading partner and the economy is based on a single product—copper—the decrease in Chinese demand for copper has been a disaster. In Zambia's Copperbelt region, at least 6,000 jobs have been lost as Chinese and other companies close down their mines.

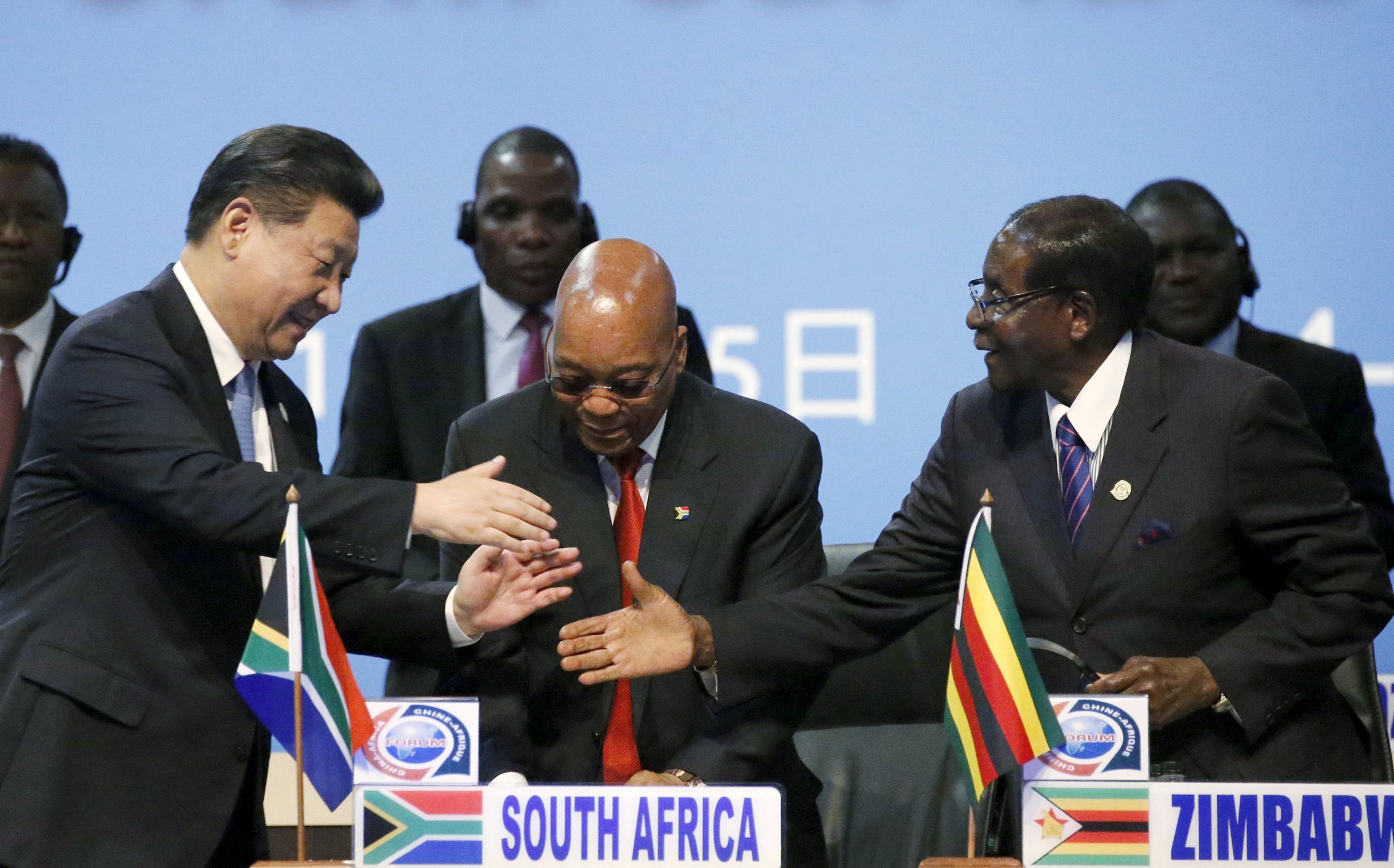

There are three things that should be said here before alarmist conclusions are drawn. The first is that, although China is Africa's largest single trading partner, its Western partners are together larger than China. The second is that the growth in trade with China has been swift and the huge volumes are recent. There is not a deep-rooted dependency on China—although there has certainly been poor planning in terms of diversified trade portfolios on the part of several African governments. The third is that Chinese plans for huge infrastructural projects and other forms of aid—Xi Jinping announced a total of $60 billion in financing for African development at a December 2015 summit in Johannesburg—are still on course. These projects will be financed from the huge Chinese foreign and domestic reserves and are not dependent on trade figures.

Insofar as the Chinese signature project—transport infrastructure—has now been updated to include in one transport corridor not only road and rail, but telecommunications and electronic communications; and health and educational facilities up and down the corridor. China is yet to lay firm plans for these developments—these could come at the G20 summit, which takes place in Hangzhou in December—but rumored ideas include both horizontal and vertical transport links passing through the whole of Africa. The vertical link would be a recapitulation of Cecil Rhodes' Cape to Cairo transport link, which was never finished, and, when combined with telecommunications development, would facilitate regional cooperation and trade on an exponential basis. Such developments would, with one stroke, bring the whole continent into the 21st century.

But the downturn in trade will worry the Chinese as well as the Africans. A key part of Deng Xiaoping's 1978 Four Modernisations'—development goals set by the then-Chinese leader—was to implicate China in the international economy. To compete with the Western economies required a base that the Chinese did not then have. Deng wanted to purchase foreign plant and machinery—or copy them—but that plant had to have raw materials. That was where Africa came in. The products of the new Chinese industry would be exported to the world, including Africa, but particularly to the economies of the West, and China would develop on the basis of its export receipts.

To an extent, the Western economic downturn in 2008 was more important to China than anything in Africa. And that is why China moved to buy an extraordinary amount of U.S. toxic debt—to try to stabilize and bolster the U.S. economy and keep its imports from China at a high level. As of May 2015, China was the world's biggest holder of U.S. debt, owning a vast $1.261 trillion of American government securities.

But at that time the Chinese economy was buoyant. It is less so now. It is still growing—at levels that are far greater than those in the West—but the downturn now appears like a corrective to something in danger of overheating after so much breakneck speed. While the Chinese could contemplate bailing out key elements of the Western economy in 2008, it will not do the same for Africa in 2016.

Besides, Africa is a huge continent of 55 countries. Geographically, it could swallow up five Chinas. Where to start?

For Africa, the lesson is stark— beware of dependency on any one partner. The Chinese economic slowdown is not going to result in another global financial crisis—China's growth rate of 6.9 percent in the third quarter of 2015 is still enviable to countries like the U.S., which recorded a mere 2.0 percent. For countries like Zambia, however, which are hugely dependent on one resource (copper) and one market (China), the lesson is—diversification. Countries like Nigeria and South Africa, which had a wider variety of trading partners, are better positioned to cope with a Chinese downturn. Other countries like Zimbabwe are so tied historically to China that they will not be allowed to fail, as seen in Xi agreeing to provide $100 billion to expand Zimbabwe's largest thermal power plant. But in order to get through a blip in Beijing, African countries like Zambia must be willing to look for alternative markets elsewhere, albeit in a world in which China is more important than ever.

Stephen Chan is a professor of World Politics at SOAS University of London. He was a member of the Trilateral Dialogue between Africa, China and the U.S.. A former international civil servant, he has published 29 scholarly books and received the OBE for "services to Africa and higher education."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.