The Supreme Court is set to hear arguments Wednesday on a sedative medication that prisons have used as a lethal injection drug, potentially violating death row inmates' rights against cruel and unusual punishment. Although the drug, midazolam, may have contributed to a series of botched executions in 2014, one death row inmate has benefitted from the controversy. He remains at the center of a medical, legal and ethical debate.

On November 13, 2013, prison officials transferred Ronald Ray Phillips from death row, where he had resided for 20 years, to the "death house" in southern Ohio. He had finally run out of appeals. In less than 24 hours, they would strap him to a gurney and inject a fatal drug combination into his veins. Just days before his scheduled death, however, Phillips made an unprecedented request—one that has kept him alive until today. He asked to give his heart to his sister, who had a heart condition, and his kidney to his mother, who was on dialysis.

When people die, their organs usually die with them. That's why the majority of heart donations are from patients who are brain dead. In these cases, the body is alive on life support, but the brain is permanently unconscious. Since the donor will never wake up, doctors may retrieve the healthy organs.

In the fall of 2013, Ohio had just instituted a new lethal injection protocol as its primary method of execution, and its effects were uncertain. The fatal drug cocktail might destroy Phillips's organs. On the other hand, if Phillips went to the operating room beforehand and doctors removed his heart while he was unconscious, they could save it. But since he couldn't survive without his heart, they would simultaneously complete the execution in a novel method that had never been considered in Ohio's capital punishment laws.

Phillips was scheduled to die at 10 the next morning. Just before 4 p.m., as prison employees headed home for the evening, the death house received a call from the governor.

"I realize this is a bit of uncharted territory for Ohio, but if another life can be saved by his willingness to donate his organs and tissues, then we should allow for that to happen," Republican Governor John Kasich said in a statement to the press hours before the scheduled execution. Kasich granted Phillips a reprieve, removing him—temporarily, at least—from the death house.

In 1993, Fae Evans, an unmarried mother of three, asked her boyfriend, Ronald Ray Phillips, to babysit. When she returned, Phillips was sitting in the kitchen while her 3-year-old daughter, Sheila Marie, lay on her bed—pale, cold and motionless.

It took the coroner two hours to count all 125 bruises on Sheila's body. Because bone can't expand to make room for blood, the bleeding in her skull was crushing her brain—pushing it out of her skull and into her neck. Blows to the chest caused bleeding around her heart. Dried blood encrusted her skin like sand on a child at the beach.

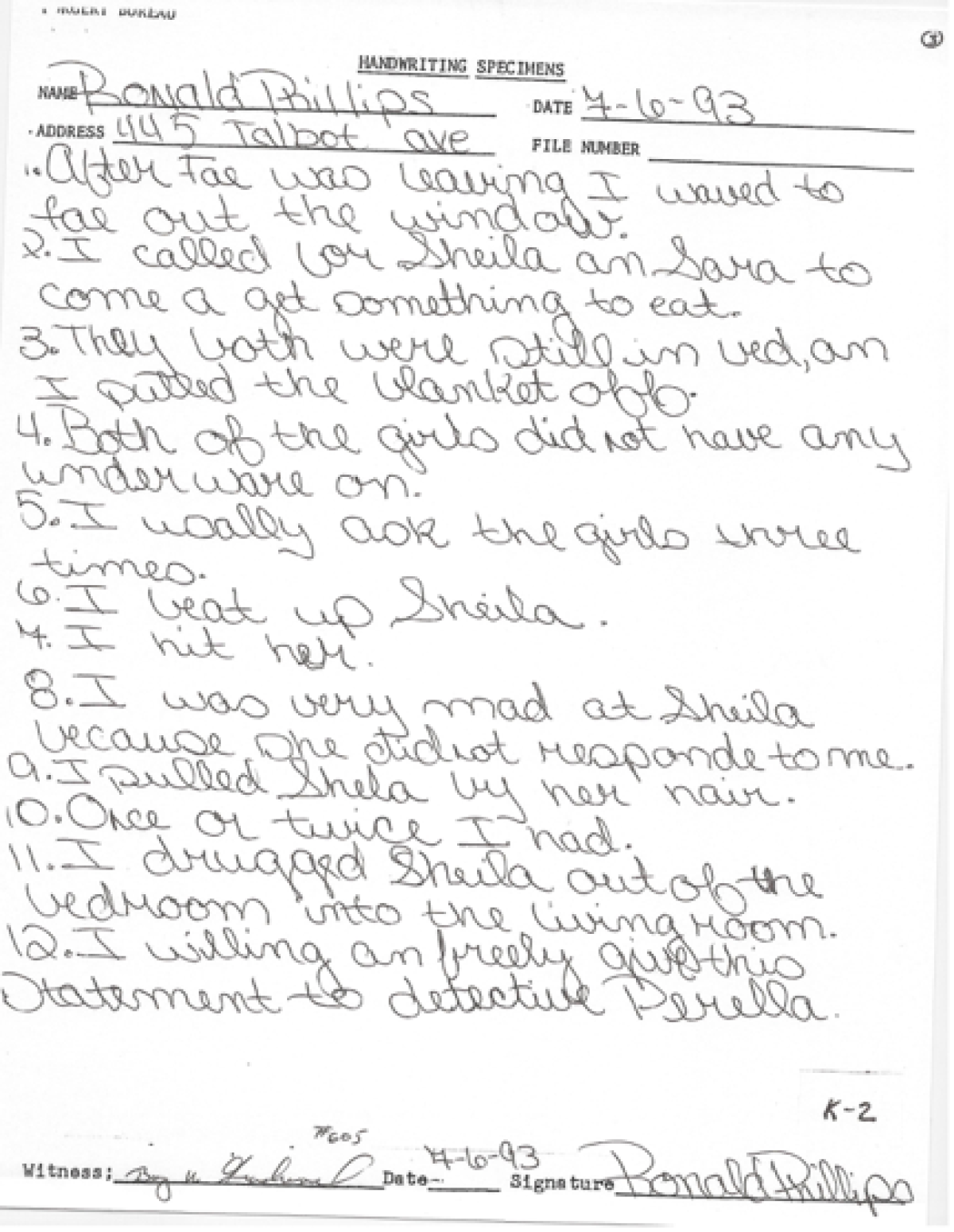

"I flipped out and beat up Sheila…hit hard…. I hit all over her body and also threw her around," Phillips confessed. "I got excited and used vasoline [sic] on her butt."

The emergency room physician who treated Sheila, Dr. Eugene Izsak, remembers her distended belly sounding like a hollow drum. Part of her intestine had died, and the air, feces and digestive juices inside had leaked out over her organs. Sheila was sodomized as the life ebbed out of her—while her belly filled with blood and her own digestive enzymes ate her alive.

The coroner scrupulously investigated the impending and prevailing causes of death and determined that the fatal blow might have predated the others. It occurred 48 hours prior to her death.

Phillips and the child's mother accused each other. "At a minimum, [Evans] saw a lot of the physical abuse," says Summit County Prosecutor Sherri Bevan Walsh. "Here you have the mom, who clearly sees her child suffering…and doesn't take her for any type of treatment."

Sheila's case resonated with the people of Summit County. Many attended Evans's trial holding teddy bears, until a court order stopped them. "We have [a] mother who's grieving the loss of her child," says Patricia Millhoff, Evans's former defense attorney. "She was the victim to me." Evans was sentenced to 13 to 30 years in prison for involuntary manslaughter and child endangering, but she ended up dying of leukemia before her release.

Phillips, meanwhile, was sentenced to death for Sheila's murder.

"Can you ever be redeemed?" Izsak asks. "Hundreds of years ago, people thought that your soul dwelt in your heart. If we transplant a heart, are we transplanting that evil?"

Doctors refused to assist in Phillips's proposed heart transplant to his sister, citing their oath to "do no harm," the same reason they don't participate in lethal injections. They couldn't end one life to save another.

Dr. Jon Groner, a vigorous opponent of physician involvement in capital punishment, wrote in a paper on lethal injection, "It turns [doctors] who dedicated their lives to healing—into killers…. A similar perversion of medical values—in which doctors and nurses became active participants in state-sanctioned killings—became the cornerstone of Nazi medicine."

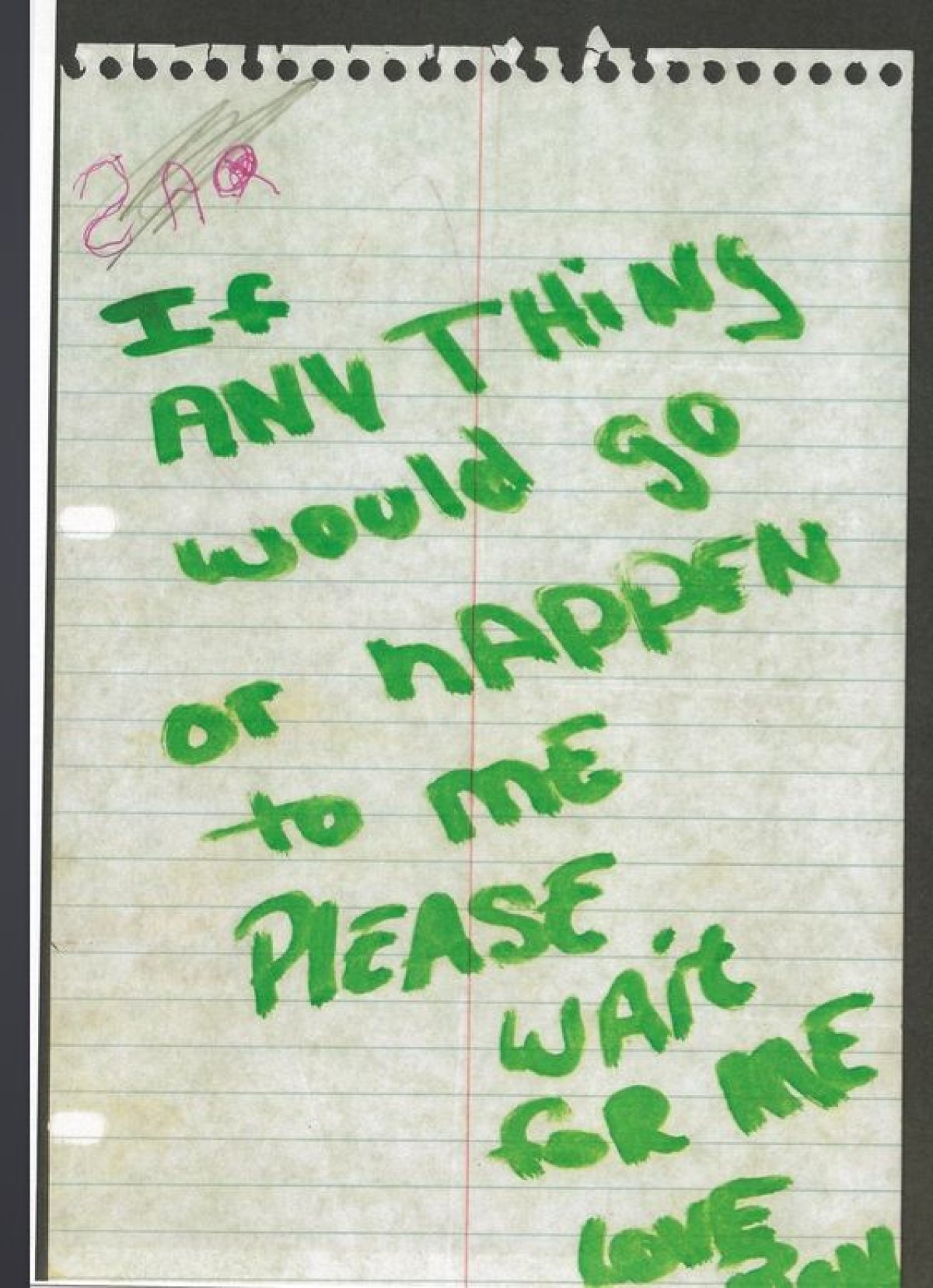

But Phillips, speaking through his attorney, pleaded for assistance from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. "Although he is preparing to die for his crime at the State's hands...[Phillips] would like his death to help as many people as possible," his attorney wrote in a letter. "Let us know…what the State will do to ensure that as many people as possible will benefit from the gift of life Ron is so generously willing to bestow as his own life approaches its end."

Local newspapers reported that Phillips might donate one lung, one kidney, one lobe of his liver and a part of his bone marrow to dying strangers. Extensive surgery would be painful, but he could still live without these organs and tissues.

But the agencies that govern transplantation refused his organs, calling the idea "morally reprehensible." Parceling out the organs to strangers could be a human rights violation. Because Phillips was a prisoner, he couldn't voluntarily consent to these procedures. The idea of saving "innocent" lives could also incentivize prosecutors and judges to favor the death penalty. Ohio denied Phillips's request to donate non-vital organs to strangers.

Yet Millhoff counters, "Why doesn't an inmate have a right to donate his or her kidney? Why is that seen as one of the rights that they've given up because they're incarcerated?"

Ohio acquiesced to Phillips's request to donate a non-vital organ to someone who wasn't a stranger—his mother. He could give her one of his kidneys if the transplant was completed 100 days before his scheduled death, affording him time to recover and comply with Ohio's mandate that death row inmates be in good health prior to execution.

Phillips's relationship with his mother was complicated. One month before his first scheduled execution, he accused his father of raping him at the age of 4 and physically assaulting him up until his arrest at age 19. He alleged that his mother also physically and verbally abused him. At Phillips's failed final appeal, his sister described prostitutes trolling the streets at night and condoms littering the sidewalks of their old neighborhood.

Both organ donors and organ recipients must undergo psychological testing to determine their suitability for a transplant. Dr. Shruti Mutalik, a psychiatrist who has not treated Phillips or his mother, posits, "Maybe this is a way of punishing her. He wants her to feel even more guilty about what she did by saying, 'Look—I am the son who is ready to die for you despite all that you did." Mutalik says, "It could also be a way of saying, 'I forgive you. The world is not ready to forgive me for what I did. They want to kill me—crucify me—for it, but here I am, ready to die for you and forgive you in my death.'"

The local children's services board had 17 separate contacts with the Phillips family over the years but could not substantiate most of the abuse claims. Prosecutor Walsh notes that Phillips's allegations of childhood abuse surfaced only during the appeals process. She questions why, if these allegations were true, Phillips and his attorneys didn't bring them to light during the mitigation phase of his original trial. At that time, if Phillips had managed to convince one juror that his prior suffering was enough to earn him a reprieve, he might have escaped the death sentence.

After repeated inquiries, prison officials determined Phillips's mother wasn't on the national waiting list for a kidney, raising serious doubts about whether she was even a transplant candidate. The month before that deadline, Phillips's attorney updated the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. Given the age of Phillips's mother, it might take six months before she would be medically prepared for surgery. "It is our belief that Mrs. Phillips is doing all she can do…to be able to accept the gift of her son's kidney."

The 100-day mark passed, and Phillips's organ donation request was denied. Perhaps his mother could have expedited her medical testing. But she might have procrastinated to protect her son. If their kidneys didn't match, he wouldn't be able to give her his organ. His reprieve would end, and he would be executed.

When death penalty opponents realized only one manufacturer could sell pentobarbital, the cornerstone in lethal injections, in the U.S., they publicized this information throughout the European Union, where the death penalty is outlawed. The pharmaceutical company, Lundbeck, issued a press release in 2011 stating, "Lundbeck adamantly opposes the distressing misuse of our product in capital punishment." The company blocked the sale of its product to U.S. prisons, spurring Ohio to develop a new cocktail. Phillips would have been its test case.

Because of Phillips's reprieve, convicted killer Dennis McGuire took his place. Reporter Alan Johnson witnessed McGuire's execution. Approximately six minutes into it, McGuire "suddenly starts gasping—deep gasps. His chest would compress, his stomach started going out," Johnson says. "I would say at least 20 times over a matter of several minutes…. They were powerful kind of choking sounds that were wracking up his body. He was definitely straining upward against the restraints. Perhaps involuntarily…his body was trying to, in its last gasp, trying to literally suck in the air and get the air into his body."

Johnson continues: "I must admit wondering, When is this going to end? Could they stop it? After a second, I thought, No, of course they can't stop it. Once you've started these chemicals flowing, it's not like you can pull the plug.'"

The McGuire fiasco prompted a federal judge to temporarily halt all Ohio executions. Nevertheless, Arizona used Ohio's protocol that summer to execute Joseph Wood. The execution lasted over two hours, with Wood gasping 640 times. It provoked another moratorium on the death cocktail.

In January 2015, before Phillips's fourth execution date, Ohio rescinded its controversial mixture, announcing a return to the pentobarbital drug class. Because Ohio has been unable to obtain this drug from Lundbeck, executions will resume in 2016 at the earliest. Phillips's fifth execution date remains unscheduled.

Phillips's unprecedented request set off a chain of events that have kept him alive till today. For over a year, he's been next up on Ohio's list of scheduled executions. But he's ridden the wave of botched executions and may transition from a temporary reprieve to a permanent one. Phillips and his attorneys declined multiple requests to be interviewed for this story.

Along the Ohio lakeshore, three teddy bears overlook Sheila Marie Evans's final resting place. For the people of Ohio, this case is very much alive. "I can't sell you my kidney. That's against the law," Izsak broods. "Should you be able to sell your organs for your life—to get off death row?"

Dr. Devi Nampiaparampil can be followed on Twitter @devichechi.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.