Updated| In the run up to Ghana's elections on December 7, the public was repeatedly reminded that its country had come to be seen as a beacon of democracy in a volatile region. In a series of competitive elections, power had changed hands back and forth between two major parties without the violence that has marred polls elsewhere in Africa.

The burden of the message was clear: people would be letting their country down, as well as themselves, if they allowed the elections to go badly.

It seems to have worked. Polling day passed off almost entirely peacefully and the public stayed calm during a protracted period of counting and tallying, during which it became clear that the governing National Democratic Congress (NDC) was falling behind, and the opposition New Patriotic Party (NPP) was on course for the presidency and parliament.

The falling popularity of the government—which has lost a score of parliamentary seats, even in some of its home areas—appears to reflect the country's ongoing economic problems, high levels of youth unemployment and falling trust in the president. In other words, a poorly performing government, in a difficult economic environment, has been punished at the polls.

In some places, NDC supporters simply stayed away from the polls: in the Ho Central constituency in the Volta region, considered the 'world bank' of the governing party on account of the massive votes that it garners in the region, the president won 53,100 votes on Wednesday compared with 62,400 in 2012.

This decline in turnout was replicated in other areas: in polling stations near Ho, turnout dropped by anything from 5 percent to 18 percent as compared to the 2012 elections. For its part, the NPP thanked an electorate that had responded to its call for change, ushering in the country's third democratic transfer of power since Ghana transitioned from military rule to multi-party democracy in 1992.

Three cheers, then, for Ghana and democracy? Yes: much credit is due to local electoral officials and to the public. In a continent where the opposition often has little or no chance of winning elections—with ruling politicians clinging to power at any price, and violence seemingly the only way to oust government–Ghana is indeed a success story.

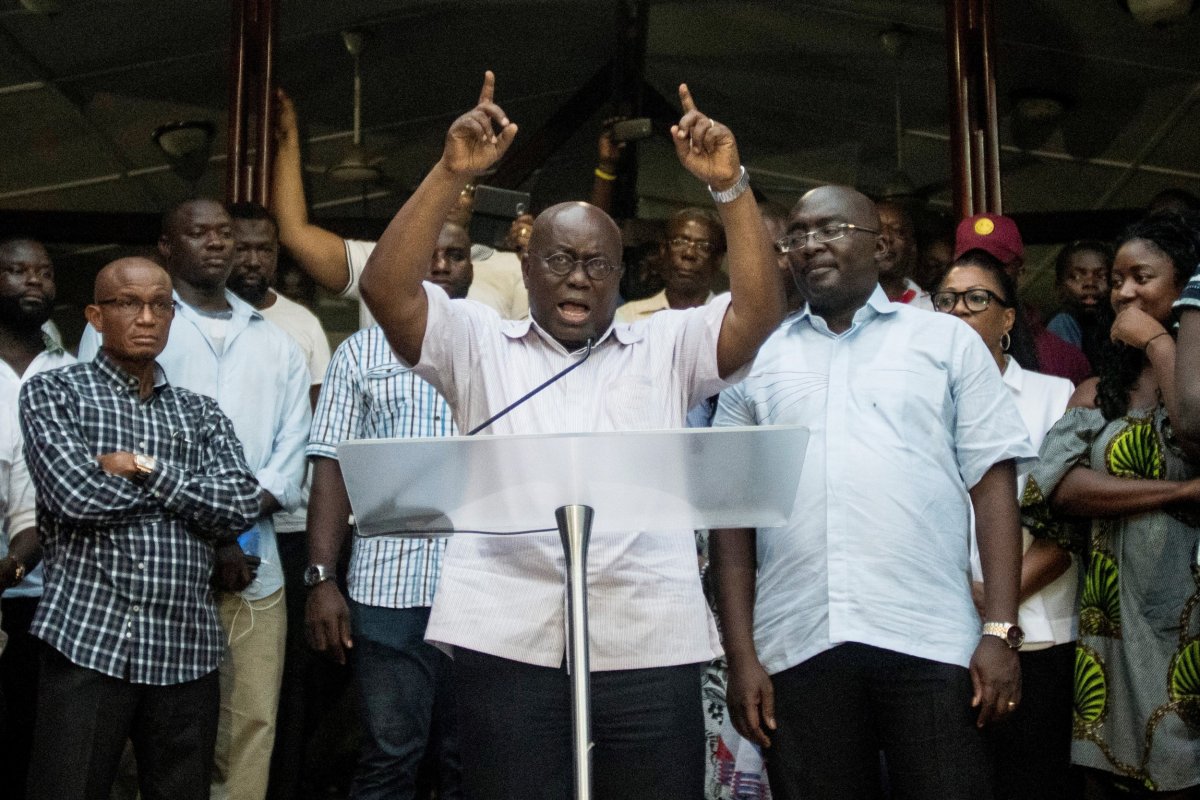

As the results trickled in, supporters of the NPP began to celebrate—even in opposition strongholds—and were largely left alone to do so peacefully by their NDC counterparts. This despite the fact that the results had not yet been officially confirmed, and that this would be the first time that an incumbent has lost an election since the reintroduction of multiparty politics in the early 1990s (other transfers of power all happened when the sitting president was standing down due to presidential term limits).

Yet Ghana is also good reminder that there are many kinds of democracy, and that elections work in different ways in different places. A nationally representative survey that we ran in Ghana in December 2015 revealed that while violence is widely considered unacceptable, there is considerable popular experience of—and expectation of—forms of behavior that might be considered malpractise; and that public attitudes in Ghana are similar to those in countries where elections have been much more problematic.

It is not just that in the run-up to the election many people did not trust the Electoral Commission—despite a generally good record. Many claimed that in previous elections they had seen ballot box stuffing and the giving of gifts to voters, and a considerable minority saw nothing wrong with this. The combination of popular suspicion of malpractice, and some popular demand for it, have pushed up the cost of elections. Many voters expect not just party a T-shirt, but to find 50 Ghanaian cedis ($12) wrapped up within it. The Electoral Commission has transparent ballot boxes to deter stuffing, biometric voter identification to deter impersonation and double voting, multiple copies of results sheets to avoid tampering. All this comes at a cost; in 2016, it is estimated that the Ghanaian polls cost some $18 per voter—far more than in Europe and North America, where elections typically cost between $1 and $3 per elector.

Candidates campaigning for office, meanwhile, have to prove that they are generous and sympathetic, and can be relied on to meet the multiple expectations of constituents once they are elected. They pay school fees for poor children; donate to church-building and funeral collections. Any group seeking support—whether it be a football team or a local hairdressers' association—knows that the election campaign is, as Ghanaians say, 'cocoa season:' time for a rich harvest. On election day, when party activists try to turn out the vote, they may be met with simple demands for cash: politicians are assumed to reap rewards from office, and the public expects to share these.

Ghana, of course, is not the only country where it is expensive to run for office. By no means every voter demands, or receives, gifts; the ruling party had more resources for campaigning and still lost, which shows that you cannot simply buy an election there. But the electoral campaign feeds into a political culture in which politicians sometimes seem more like intermediaries sent to secure rewards from government than representatives of the people. Once elected, they will be expected to continue in this role; when they visit their constituencies they are met by a queue of hopefuls seeking help in getting a government job, or a place in a good school for their child, or a donation to the cost of medical care.

Demands are collective, as well as individual. Our survey found that that a majority of Ghanaians expect elected politicians to steer development projects towards their constituencies to secure re-election (incidentally, the last few weeks have seen the rushed 'commissioning' of multiple projects, some more complete than others). The NDC lost partly because voters in the Volta Region—long a party stronghold—felt that they had not benefited as much as other parts of the country in recent years, and stayed away from the polls.

Political parties are strong in Ghana, and this has contributed to political stability. Yet they work as consortia rather than in pursuit of policy. Comically, each major party delayed releasing its campaign manifesto this year, for fear that the other parties would steal its ideas. Parties are networks for business, employment and mutual support; securing control of government is important not because of policy differences, but because it makes them much more able to reward members. The new NPP government would, like its predecessor, appoint thousands of its supporters into positions that it controls, from municipal chief executives to ambassadorships. In turn, those appointees will give contracts, and jobs, to others.

Nothing about this is uniquely African—it is a feature of patron-client politics in places such as Latin America and also, to an extent, the United States. But there is a cost to this, in terms of efficiency and accountability.

Ghana is a success story. Coming a few days after the dramatic change of government in Gambia, this is heartening evidence of the power of the electoral process. But the newly elected politicians—from the president down to local MPs—will struggle to reward their supporters, and meet the expectations of a hopeful public.

Nic Cheeseman, associate professor in African politics at the University of Oxford ( @fromagehomme), Gabrielle Lynch, associate professor of comparative politics at the University of Warwick (@gabriellelynch6), and Justin Willis, professor of modern African history at the University of Durham, are part of an Economic and Social Research Council-funded research project (ES/L002345/1) on the impact of elections in Uganda, Kenya and Ghana.

This article originally incorrectly referred to the NDC as the National Democratic Convention. It is the National Democratic Congress.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.