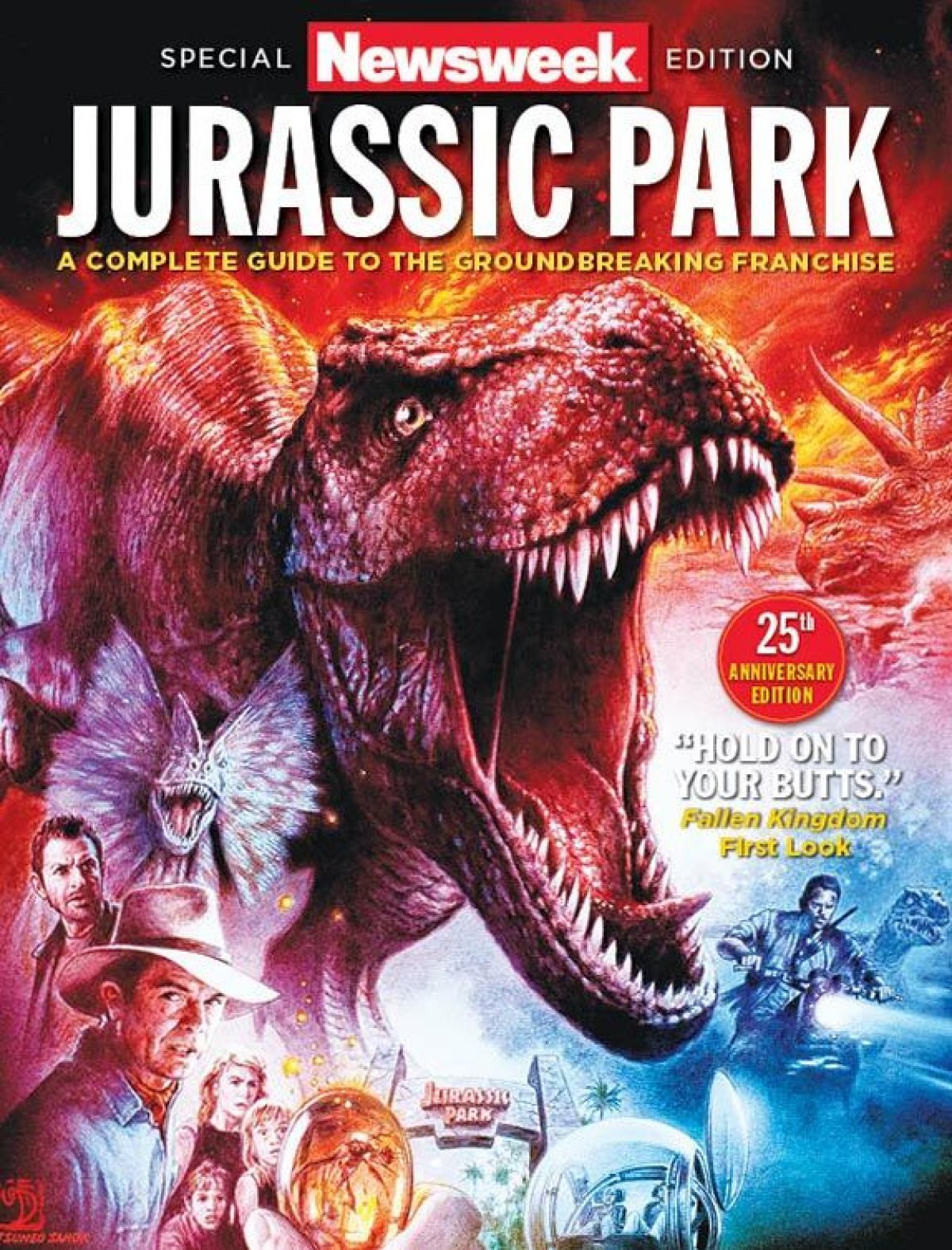

This article, along with others celebrating the 25th anniversary of the groundbreaking franchise, is featured in Newsweek's Special Edition: Jurassic Park.

Her graceful neck rises higher than the trees, like a giraffe in slow motion, her liquid eyes staring curiously, then dismissively, at the gaping humans; she returns to her grazing as if these late-model mammals were no more worthy of note than their scruffy shrewlike ancestors, with whom she shared the Earth 130 million years ago. The lack of interest is not mutual. The beast on that rolling meadow looks for all the world like a living dinosaur—a real, respiring, mothering, thundering, leafchomping Brachiosaurus. The awe-struck humans on screen are convinced that this monster of the Mesozoic has been brought back to life. We can tell they're convinced by the actors' bugging eyes and dropped jaws.

OK, so not even the makers of Jurassic Park, this summer's blockbuster-to-be, expect to achieve that crucial suspension of disbelief in the audience on the strength of the acting. And although director Steven Spielberg spent two years in pre-production working with the computer maestros and model-makers who created such wondrously realistic beasts as a Triceratops with a bad stomachache and a Tyrannosaurus rex with an appetite for cars carrying cherubic children, special effects alone can't persuade audiences to pretend that dinosaurs have burst the coffin of extinction. There is only one hidden persuader in science fiction: a solid kernel of scientific plausibility.

In Spielberg's $60 million Jurassic Park, this hard center is a theory barely 10 years old. It holds that snippets of the genetic material DNA, extracted from mosquitoes that sucked dinosaur blood and then became fossilized in amber, can bring dinosaurs back to life. "This movie depends on credibility, not just the special effects," Spielberg told Newsweek. "The credibility of the premise—that dinosaurs could come back to life through cloning—is what allowed the movie to be made."

All great science fiction must be science first and fiction second. Even more, it must tap into the reigning scientific paradigm of its era. For Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, that paradigm was electricity, the sizzling lightning bolts and arcing volts that were powering the nascent Industrial Revolution. For Godzilla, it was radioactivity and the bomb. For Jurassic Park, it is biotechnology. The manipulation of cells and genes has produced three cloned mice, pigs containing human DNA, tomatoes with flounder genes—and lots of people who fret about where it's all leading. According to the 1990 Michael Crichton novel that Jurassic Park is based on, biotech is headed toward using mosquitoes and bloodsucking flies to undo the dinosaurs' extinction.

Both book and film unfold in the world's greatest theme park: a gentle Brachiosaurus herd strides in meadows, rapacious Velociraptors eat oxen alive. The mastermind behind the park bankrolled paleontologists, geneticists and computer scientists to create the dinosaurs out of nothing more imposing than bugs in amber. The premise is that after insects fed on dinosaurs, they flew to a sapoozing tree. In their postprandial languor, they got stuck. For good. Resin fossilized into the dusky gemstone amber, preserving intact the insect and, perhaps, its last supper. The rest of the dinosaur reanimation is, as they say, just biochemistry.

Two weeks into the filming of Jurassic Park, biologists Raul Cano of California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo and George Poinar Jr. of the University of California, Berkeley, announced that they had cloned DNA from a 40 million-year-old bee preserved in amber. Almost simultaneously, scientists at the American Museum of Natural History in New York reported that they had cloned the DNA from a 25 million-year-old termite trapped in the golden mineral. "Jurassic Park has at least one big toe in real biological research," says Poinar. "Ancient DNA is indeed being extracted and cloned from extinct organisms preserved in amber."

The science rumor mill is buzzing with word that it's about to be done. "Someone will do it," says Cano. "And soon." (But not to clone a dinosaur: Horner and Cano are interested in comparing dinosaur DNA to that of living reptiles and birds to determine their evolutionary relationships.)

Of course, even if someone retrieved dinosaur DNA, Disneyland wouldn't have to worry about competition from a real-life Jurassic Park. None of the ancient DNA harvested from amber or fossils, notes the Natural History Museum's Ward Wheeler, is longer than 250 of the units (called base pairs) used to measure DNA. The human genome contains 3 billion base pairs. Dinosaurs might have had between 1 billion and 10 billion, estimates the museum's Rob Desalle, who with Wheeler helped isolate the 25 million-year-old termite DNA. Even if scientists discover every single one of the base-pair chains, joining 40 million of them in the right order would be like taping together a book that has been chopped into individual letters. "And even if we could splice them all together," says Desalle, "there are all sorts of development things that happen in the egg that we don't know about."

Here's where the prospects for re-creating Triceratops dim. You need a lot more than DNA to build a dinosaur, says David Botstein, chairman of the genetics department at Stanford University, who gets a brief mention in Crichton's book. You need a cell. Only in the cell, with its biological signals that tell genes to turn off and on, can DNA direct the creation of an embryo.

The bigger challenge to cloning a dinosaur, even assuming one had a cell full of DNA, is that cells from anything but an embryo seem to have forgotten how to make the complete animal. It is adult DNA, of course, that is the raw material for Jurassic Park and the likely discovery of scientists looking for dinosaur genes in fossils. Scientists do not know when the DNA in dinosaur cells forgot how to make the complete creature.

Cloned dinos aren't prohibited by any law of nature. And in science, the saying goes, what is not strictly prohibited is, in principle, possible. Jurassic Park's vision of hubristic scientists determined to shape the future, damn the consequences, recalls the physicists of the Manhattan Project. When they set off the Trinity test in Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1945, they were not sure that the atomic bomb would not ignite the planet's entire atmosphere, consuming Earth in a world-ending holocaust. They did it anyway. Crichton sees in Jurassic Park a reflection of science's delusion of control. "Biotechnology and genetic engineering are very powerful," he says. "The film suggests that [science's] control of nature is elusive. And just as war is too important to leave to the generals, science is too important to leave to scientists. Everyone needs to be attentive."

This article, from the Newsweek archive, 6/13/1993, by Newsweek staff, was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition: Jurassic Park. For more celebrating the 25th anniversary of one of the greatest monster movies of its time and a Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom first look, pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.