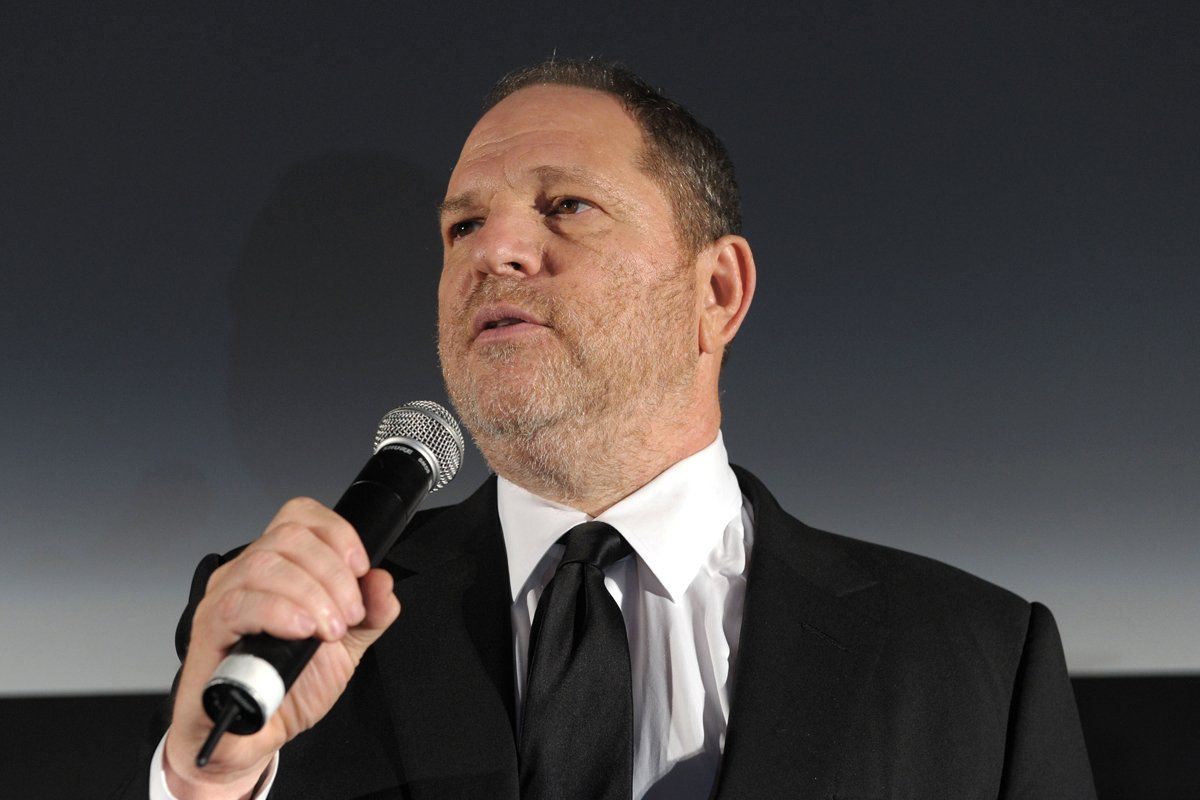

In the wake of the several dozen sexual harassment and assault allegations against Harvey Weinstein, women are being compelled to tell their stories and report such hostile work environments to their company's human resources department.

The problem is, HR doesn't exist to protect the employees — it exists to protect the company.

Statistics show that a majority of women has experienced "unwanted and inappropriate advances" from male colleagues — and a quarter of victims said the male colleagues who harassed them had power over their careers. Yet the vast majority of women — 75 percent, according to an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission study — never bother to report workplace sexual harassment out of fear of retaliation or not being believed.

And 95 percent of women say they've seen no consequences for accused men.

"There's a misconception [about] HR," Bryan Arce, the managing partner at New York City firm Phillips & Associates, tells Newsweek. "The HR department has an inherent interest in helping the company, because the company's name is on their paycheck."

In cases when women do report sexual harassment to their company's HR department, many find nothing comes of it; instead, they're sent back to their desks to work alongside their harassers as though nothing happened. Arce says one of the phrases he uses most often in his investigations into these oversights is "swept under the rug"; he says most HR departments simply hope an employee's harassment complaint will "go away."

Employers can disappear an employee's complaint that easily — sometimes by disappearing the employee herself.

Kim Langen, a 34-year-old in New Brunswick, Canada, tells Newsweek she was fired just five months into her job as a college recruiter for standing up to a manager who was relentlessly harassing her. Langen says he'd ask her if she would ever cheat on her husband, tell her about cheating on his girlfriend and brag about the size of his penis.

When Langen rebuffed his advances, the manager got hostile, bullying her and putting her down.

Langen thought HR might offer her some help. She was wrong.

"HR told me, 'We don't want to get involved in this,'" Langen says. "I was dumbfounded to say the least."

Langen says she was in such a state of shock, she'd said nothing in response. She simply left the office and thought to herself, "Where do I go from here?"

Langen went home and spoke to her husband, and they decided she should stand up to her boss and risk getting fired. She did, telling the manager she demanded to be treated with respect and integrity. A month later, she found herself in the HR office again, this time for her firing.

"I told them, 'The minute I was in a situation where I had to stand up for myself I knew I would be here,'" Langen recalls.

A spokeswoman from the Society for Human Resource Management, the world's largest society of HR professionals, argues that HR does what it can to safeguard against workplace harassment. After the sexual harassment charges aired by Anita Hill against future Justice Clarence Thomas, plus the Supreme Court rulings in the Ellerth and Faragher cases of the 1990s, which expanded employers' liability in sexual harassment cases, companies devised new policies, including training courses and much-mocked "scenario" videos. Companies also increasingly bought insurance to protect themselves from lawsuits after one worker harassed another.

California, home to the West Coast wing of The Weinstein Company, has some of the country's strictest anti-harassment guidelines, being the only state that requires supervisors in companies with more than 50 employees to undertake at least two hours of harassment training every two years. (It's unclear if Weinstein underwent the training. Newsweek asked the state's Department of Fair Employment and Housing, which would not provide that detail, and the Weinstein Company did not return calls. The agency did say it had not received not a single harassment complaint against The Weinstein Company in the last five years, which again speaks to the culture of silence or lack of trust in enforcement agencies.)

Such practices have been the norm in workplaces for years, yet sexual harassment continues. The reason is clear: Anti-harassment policies and procedures are just "symbolic compliance," UC Berkeley professor of law and sociology Lauren Edelman tells Newsweek.

"They're meant to protect the company," says Edelman. "The reason they're created is because they've become widely accepted as indicative that the company cares about stopping harassment even when they don't."

Even companies that go to lengths to provide trainings to prevent workplace harassment might find they have the opposite effect. Edelman cites a University of Nebraska at Omaha study which found men who completed a 30-minute harassment prevention training were less capable of identifying instances of sexual harassment and more likely to blame women who allege harassment. Edelman blames the "cartoonish" nature of many harassment training courses, which often include scenarios that stereotype women as "passive, emotional and duplicitous."

Despite the shortcomings of HR training, Edelman says there's been little research into alternatives for companies that genuinely wish to tackle the problem of workplace harassment.

"There hasn't been sufficient study at this point about what works and what doesn't," she says.

HR professionals themselves have attested to the limits of what they can do to prevent workplace harassment and how their very job description is often antithetical to helping victims.

"Our job in HR is to retain the best and brightest talent and also to handle employee complaints," Laurie Ruettimann, a former human resources leader turned HR consultant, wrote in Vox. "When these conflict and the best and brightest talent is the harasser, HR is incentivized to protect the harasser."

Often that means firing the alleged victim — not the alleged harasser. When an employee makes a complaint of harassment, HR has an obligation to report it to the company's higher-ups, who then make a judgment — often not about what's to be done with the alleged harasser, but about what's to be done with the alleged victim.

"The company begins looking for ways to extinguish the victim as a threat," Davida Perry, a sexual harassment lawyer at Schwartz Perry & Heller, tells Newsweek. "The tables get turned and suddenly a client is being accused of horrible performance; they're getting written up or put on a performance plan. Part of 'handling' a victim's complaint usually involves the company looking for something they can use against the employee who lodged it."

Weinstein launched a media crusade against his accusers, reportedly planting stories in tabloids meant to trash the reputations of the women who had tried to ruin his. According to the New York Times, the Hollywood studio executive recruited "a team of top-shelf defense lawyers and publicists" to strategically dismantle the credibility of Ambra Gutierrez, the model who reported Weinstein to New York City cops for groping her. Weinstein's alleged smear campaign is extreme, to be sure.

That kind of coordinated character assassination is horrendous coming from a Hollywood big shot — but it's especially outrageous from a woman's own company.

Yet HR offices often work with employers to shush up harassment claims by moving the complainant to a different department. Such was the fate of Perry's current client, whose supervisor retaliated against her for rejecting his advances on a business trip. Afterward, he'd stopped talking to her at work and had stopped giving her assignments. Perry says her client had tangible proof of this retaliation and delivered it to HR, whose representatives responded only by "forcing her out of the job she loved."

"My client is out of a job; the guy who harassed her still works there," Perry says. "This can't be how the story ends."

Perry's job is to make sure it isn't. But there are many more women who can't afford to pay a lawyer, who can't risk complaining to HR, who feel powerless to do anything other than stay quiet and hope the harassment stops. It almost never does. If they can, some of these women might decide to quit their jobs — in the case of many of Weinstein's alleged victims, they left the entertainment industry altogether. Others stayed and endured the harassment. Most were silent for decades

Those who have spoken up have faced the consequences.

Langen has a new job, where she says she's treated with respect and dignity. But she no longer works in college recruiting.

"Once I stood up to my supervisor," she says, "I knew my fate was sealed."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Marie Solis is a politics writer at Newsweek focusing on women's issues. She's previously written for Mic, Teen Vogue, Bustle, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.