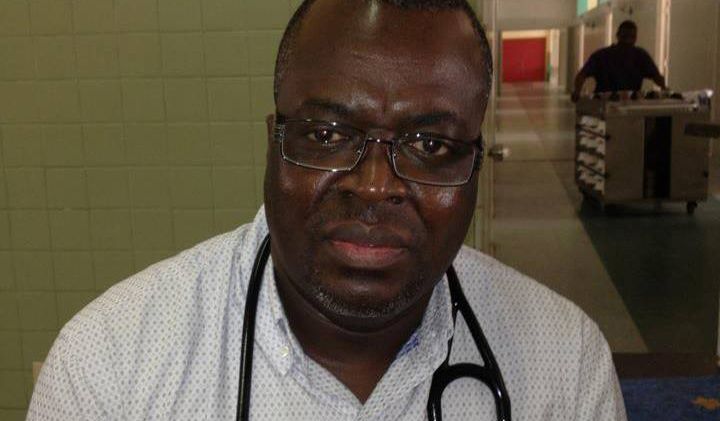

Dr. Senga Omeonga, a surgeon in Liberia, thinks he knows how he got Ebola.

On July 15, Omeonga's boss walked into his office at St. Joseph Catholic Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia full of worry. The hospital director told Omeonga he had shaken hands with a man who was later diagnosed with Ebola, and now he was feeling ill—the director had been vomiting, had a headache, and was running a high fever. But two days later, when the diagnostic test came back negative, that worry was banished, and Omeonga and his colleagues began caring for the director as they would a typhoid or malaria patient. "We wore gloves, but we were not very strict at all."

A week later, the director's symptoms got worse, and he was tested again. This time, it came back positive for Ebola—the first test was a false negative. Suddenly, everyone who had cared for him was a possible Ebola case. The hospital became a quarantine zone. The director died on August 2, the same day Omeonga began to feel sick. Of the 20 health workers who had been in contact with him during that week, 15 came down with Ebola a short while later, including Omeonga. Nine of Omeonga's colleagues died. He and five others survived.

Omeonga spoke on the phone with Newsweek from his home in Liberia where, five weeks after being declared Ebola-free, he is still working to regain his strength.

What does having Ebola feel like?

It's difficult to describe. I'm a very healthy person. It was my first experience with having a sickness like this. It's very very bad. You're extremely weak, with intense fatigue. You can't do anything. You're vomiting, and you're having fever, and a headache. It's not like malaria. Malaria, you can be walking around, and you can take your medicine. Ebola is very very different. It's like your body doesn't belong to you anymore. You feel helpless. Someone needs to care for you at all times.

What was it like being quarantined in the hospital with all of your colleagues?

We all had the same symptoms. Every day, more and more of us started complaining of the symptoms. Sometimes we were laughing together and everything was fine, that was only in the beginning. But once everyone got really sick, no one could get up from their bed.

They were only taking the people who were very, very sick to the ETU [Ebola treatment unit] first. I was one of the ones who was relatively stable, so I waited longer. It was the only ETU in the Monrovia area. Just 40 beds. I had to wait one week to get a bed. They were giving priority to health care workers but even still I had to wait one week.

You were one of three health care workers at your hospital to receive the experimental drug ZMapp. What physical state were you in when you were given the drug?

I received the ZMapp one week after I was admitted to the ETU. I was relatively stable: My diarrhea had stopped at that time. I was no longer vomiting, and I was forcing myself to eat a little bit. I had been much worse before. I was not really that sick like the other patients who were not able to get up from the bed.

All I can say is that ZMapp may have speeded my healing. Maybe I would have survived anyway.

Were you concerned about taking an experimental drug?

I was a little bit concerned. But I was also not concerned because I had no choice, this was my chance to be well and not to be killed. If it would help me to survive, I would sign consent.

How did your colleagues fare with the ZMapp?

Unfortunately one doctor who was supposed to receive the ZMapp died the same day it came. So they gave it to another [physician's assistant] who was in a coma. Thank God they did that, because the chance of survival was very slim for her. But after receiving the ZMapp, she made a recovery that made everyone amazed. The next day, she was out of the coma. In a few days she was walking. The other doctor [who received ZMapp] died. So among us three, one died and two survived.

Did you have a reaction to the ZMapp? Were there side effects?

I had a reaction on the last ZMapp dose, but I think it was due to medical error, because they did not give me the antiallergy medication they were supposed to give me. I had an anaphylactic reaction, so my body was starting to chill and I had difficulty breathing and a severe headache. It was a really bad feeling. So they had to stop and give me cortisone. After that I was just very weak. I couldn't get out of my bed. Later I started to feel better. I spent two and a half weeks in the unit.

How do you feel now?

I've been a month and a week at home. There's a lot of improvement every day. I'm getting my strength back. But the recovery is a very slow process. I still have joint pain, the weakness is still there. It's hard to say when I'll be completely better—maybe in another month. Nobody really knows about recovery after Ebola because the virus destroys everything in your body.

Do you have family with you?

My family isn't here with me, otherwise they would have all been infected. They're all in Canada.

What will you do when you feel completely healed?

I'll go back to my work. I'll care for the patients as usual. I'm immune for the same strain of Ebola I was infected with. This one is the deadliest one, so if you're immune to the deadliest one, then I maybe could also resist other ones.

I will still use the protective equipment. This is a must. I can still infect another patient, by carrying it from one patient to another.

The hospital has been closed for almost two months now. The ministry of health has sprayed the hospital, and we're in the process to reopen the hospital next month.

Why do you think so many health care workers have contracted Ebola? Is there a similar problem they're all facing?

We don't have enough Personal Protective Equipment [PPE]. That's a big challenge. That's one of the biggest problems. That's why a lot of hospitals have closed. There's not enough PPE for everyone to have it. They might give you gloves, but maybe not the gown. Or not the mask. But now, with the international help, it's getting better, and if we don't have PPE available, we don't treat the patient. But then [the patients] go back home, and infect their communities. It's a big problem.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zoë is a senior writer at Newsweek. She covers science, the environment, and human health. She has written for a ... Read more