Today, websites including Netflix, reddit and Etsy are participating in a day of protest to draw attention to Net neutrality—the idea that Internet service providers (ISPs) should treat all Internet traffic equally. If the campaign is successful, the U.S. would be joining a handful of countries that have passed Net neutrality legislation.

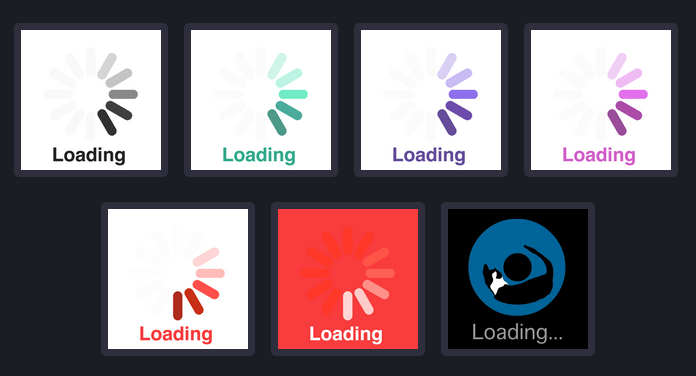

As part of "Internet Slowdown Day," sites will display a "loading" icon to symbolize how a lack of ISP regulation would result in slower website services for some. Without Net neutrality, ISPs could provide a "fast lane" to favored content (websites that pay), allowing it to load more quickly. In turn, ISPs could also downgrade the speed of other content (websites that can't pay).

Opponents of Net neutrality believe by banning big websites from paying providers to pioneer ways of making their service faster, network innovation would freeze. This in turn would make networks less profitable for these companies and remove a reason for investing in network infrastructure.

They have also voiced concern that the crafting of effective Net neutrality rules would be difficult for an ever-changing Internet. But Net neutrality advocates worry that without it, new companies would have a harder time breaking into the market. Some think ISPs would strategically slow websites that would compete with favored content.

Internet Slowdown Day organizers hope visitors to participating sites will click the loading icon, learn more about Net neutrality, and share their thoughts with the FCC before the period allotted for collecting public comments ends on September 15. A ruling is expected as early as the end of the year.

If the U.S. does adopt Net neutrality, it would be joining three other countries—Chile, Netherlands and Brazil—that offer some hints at how Net neutrality could turn out.

Chile was the first on the scene when it made Net neutrality provisions to its General Telecommunications Law in 2010. But Net neutrality opponents, as well as some advocates, are critical of Chile's blanket application of the principle. On June 1, 2014, Chile put an end to giving big companies "zero-rating" access to their services—a widespread practice in developing countries. Zero-rating refers to large companies, like Facebook, being able to make deals with mobile operators to offer the most basic version of their service without charging customers for data use. The details of these deals are unclear, but big companies may pay mobile operators for the privilege.

While zero-rating may be giving big companies an advantage by exposing more people to their services, Net neutrality advocates claim the practice goes against open Internet principles—giving an equal opportunity to access. Mobile Internet penetration is very low in Chile (only 24.8 percent have mobile broadband subscriptions). By blocking data-free access, Chile prevents its citizens from fully experiencing the usefulness of mobile Internet, and restricts them from previewing it before purchasing data.

The Netherlands became the second country to adopt Net neutrality, in 2011. It bans mobile telephone operators from blocking or charging consumers extra for using communications services that are Internet-based. As a result, mobile operators there raised charges overall to compensate for revenue lost due to the restrictions, but advocates still hail the law as a consumer victory.

The European Union is in the process of following the Netherlands' lead. On April 3, 2014, the EU adopted a Net neutrality amendment as part of its larger movement to consolidate the telecommunications policies of member countries. Though the amendment has yet to take its final form (member states must all review and accept the wording) the amendment states, "traffic should be treated equally, without discrimination, restriction or interference, independent of the sender, receiver, type, content, device, service or application."

The most compelling arguments against the law, made primarily by ISPs in the EU, are unique to the EU. Since the main players Net neutrality aims to keep in check—Facebook, Netflix, YouTube, etc.—are based in the U.S., ISPs in the EU argue that in order to make money and support the industry at home, they need to make deals with these companies. The ISPs in the EU are currently lobbying member states to alter the amendment in their favor before signing on. And analysts predict they will be at least partly successful. The review process is expected to be complete by the end of the year.

The most recent addition to the small club is Brazil, which adopted the legislation on April 22, 2014. It bars telecom companies from charging higher rates for access to content requiring more bandwidth, such as movie streaming. It not only limits the gathering of metadata but also holds the large companies accountable for the security of Brazilians' data, even if it is stored abroad. This means websites like Facebook and Google will be subject to Brazil's laws and courts. The legislation also establishes that service providers are accountable for content published by users and must comply with court orders to remove libelous or offensive material.

The law, dubbed Brazil's "Internet Constitution," has impressed experts. Tim Berners-Lee, the man credited with inventing the web, praised the legislation for ensuring the openness and decentralization of the Internet while balancing the rights and duties of governments, corporations and users.

The FCC previously put forward two proposals to protect Net neutrality, but both were struck down by U.S. courts. Since the release of its latest plan in May, however, the FCC has received an overwhelming number of comments in favor of Net neutrality. Will Internet Slowdown Day be the final push needed to make sure all traffic is treated equally under the law?

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Lauren is a reporter covering technology, national security and foreign affairs. She has previously worked on award winning teams at ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.