Not many leaders faced calls for impeachment before they had even taken office, but that was the case for Donald Trump. As far back as March 2016, conservative talk show host Rush Limbaugh predicted, "They'll be talking impeachment on Day Two, after the first Trump executive order."

In a September 2016 paper in the Oregon Law Review, law professor Christopher Peterson argued that the fraud and racketeering charges faced by then-candidate Trump were grounds enough for his removal from the White House should he win the election. That was two months before the election.

Now, more than two years into Donald Trump's presidency, calls for impeachment revved up with every tidbit from the Mueller investigation. Bookmakers claimed there was a 59 percent probability that President Donald Trump would be impeached in his first term. And the American public didn't seem all that averse to the idea, either: In January 2019, an ABC News/Washington Post phone survey found 40 percent of participants supported impeachment.

Democrats have held a majority in the House since the 2018 midterms, upping the odds that articles to impeach Trump could pass. But even so, how easy is it really to get rid of a sitting president? Newsweek looked at the mechanisms in place to remove a president from office.

What Is Impeachment?

According to the Constitution, the president "shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors." Despite popular misconception, impeachment does not mean immediate removal from office—it's just the first step in the process of deciding whether a serious crime has been committed.

The American concept of impeachment is borrowed from England, where the first political figure to be successfully impeached was Michael de la Pole, the Earl of Suffolk, in 1386. But the U.K. began phasing out impeachment around the same time the concept was drafted into the American Constitution. (It's worth noting the British version also addressed ''high crimes and misdemeanors," the vague phrase we still use today.)

Impeachment is really just one of many mechanisms that keeps the balance of power in check among the three branches of government. The president, Congress and the Supreme Court all have ways of stepping in if another branch overreaches. The president can veto legislation created by Congress, for example, and the justices of the Supreme Court can overturn unconstitutional laws. Impeachment is Congress's way of exerting control over the president if exceptional circumstances demand it.

How Does Impeachment Happen?

The impeachment process starts in the House of Representatives. Often, it's individual representatives who bring forth articles of impeachment themselves as traditional bills. Alternately, the House can pass a resolution authorizing an inquiry.

Traditionally, the House Judiciary Committee decides whether or not to conduct an investigation into allegations against the president. If an investigation is approved and finds incriminating information, the committee will draw up articles of impeachment. These documents lay out the charges against the president; once they're introduced, a simple majority is needed to move the proceedings out of committee.

At that point, it's up to the Speaker of the House, currently Democrat Nancy Pelosi, to decide whether—and when—put it to a vote by the full chamber. If the Speaker does put it to a vote, a simple majority is needed in the full chamber to approve the articles.

If that majority is achieved, the president has officially been impeached.

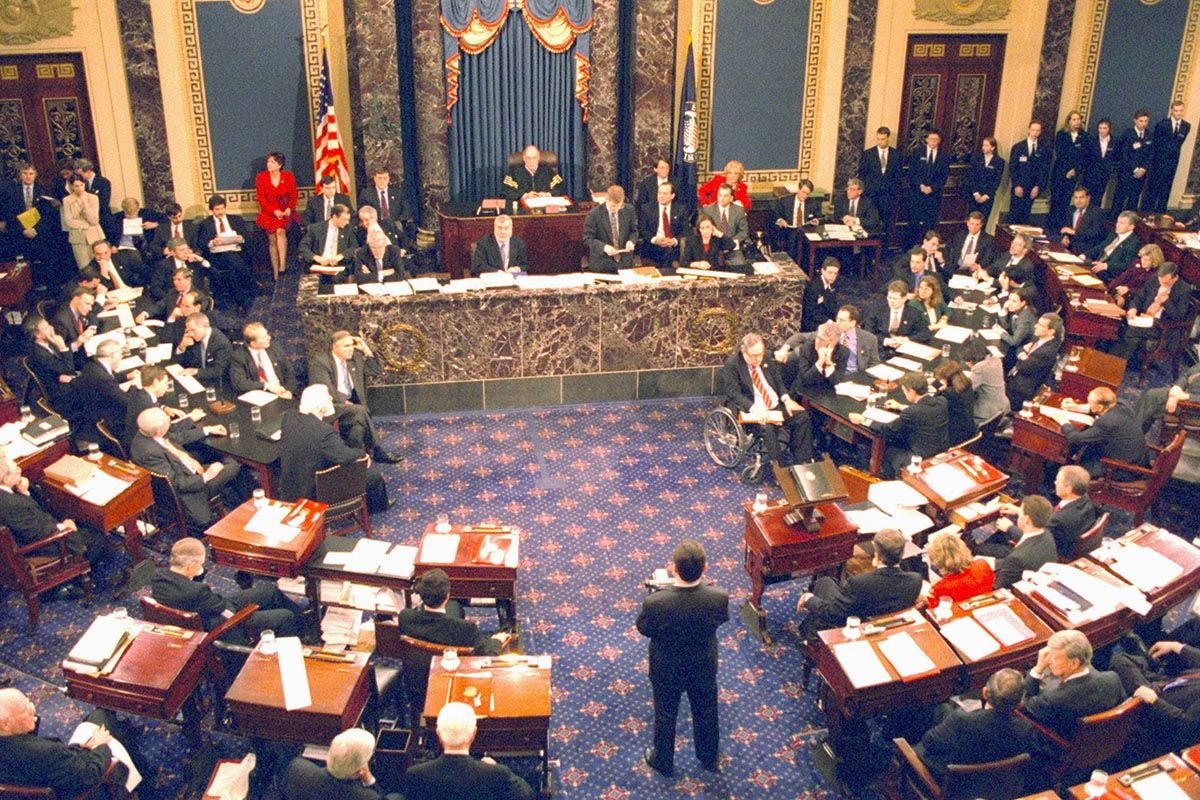

But that doesn't automatically mean he or she must leave office—or is facing criminal charges. After the president is formally impeached, the process moves to the Senate, where the case is judged in trial-like proceedings overseen by the Chief Justice of Supreme Court. A selection of House members make the case for the president's removal, which is voted on by the full chamber.

Unlike the House, the Senate needs a firm two-thirds majority to secure a conviction, so 67 senators need to vote to convict the president. That high threshold makes it harder for partisan issues to drive an impeachment, theoretically preventing one party from just ousting the opposition leader. But if this majority is reached, the president is essentially fired, and the Senate can then decide to disqualify them from ever holding a public office again.

There is no appeals process—the Senate's decision is final.

What Happens if a President Is Removed From Office?

If a president is impeached, the vice president becomes the next president. This makes attempting impeachment for partisan reasons look less attractive—after all, the vice president was handpicked by the president to be his successor.

Vice President Spiro Agnew also faced criminal accusations when President Richard Nixon's impeachment process began, leaving officials with the worrying prospect of disposing one crook only to replace him with another. In the case that the VP is impeached the same time as the president, the Speaker of the House would become president.

Has a President Ever Been Impeached?

Only two presidents in American history have ever been impeached. And both were found not guilty by the Senate vote, allowing them to retain the presidency.

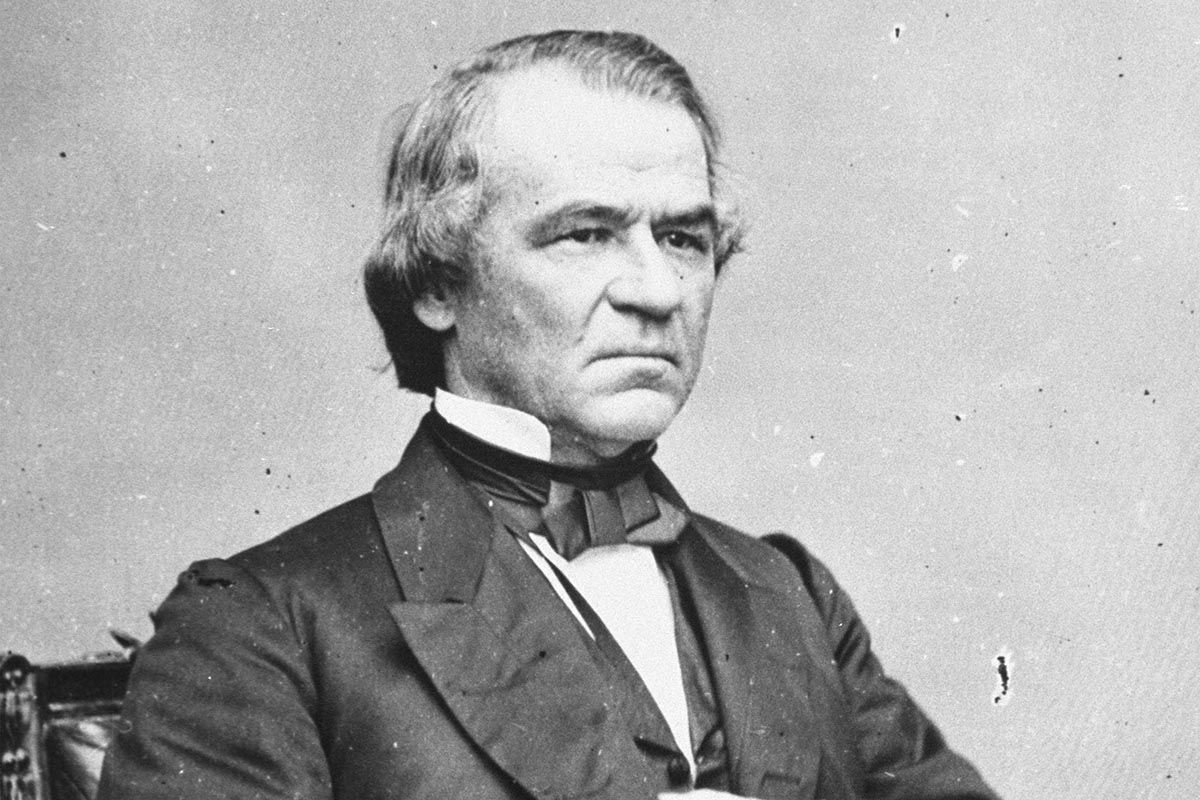

Democratic President Andrew Johnson was impeached in 1869, during Reconstruction, when America was rebuilding after the Civil War. Republicans had seized control of both houses of Congress and set about passing laws to protect and elevate freed slaves. They advocated for allowing blacks to vote (presumably Republican) and wanted top Confederates to be punished. (At this time, Republicans were largely from the pro-abolitionist North, and advocated big government, while the Democrats were largely from the Confederate South, and urged curbing federal power. The parties "switched" stances around the turn of the 20th century.) Johnson, on the other hand, simply wanted to welcome back to the Union the states that had seceded.

After a number of clashes, the House, in March 1868—controlled by the Radical Republicans, a faction of politicians committed to the complete emancipation of and establishing rights for slaves—approved 11 articles of impeachment. The Senate trial began a few days later, and Johnson was acquitted by a single vote.

A number of Republicans defied the party line to vote against the impeachment for fear that it would lead to Congress wielding too much power. The crimes levied against Johnson were vague, and included giving inflammatory speech.

"I cannot agree to destroy the harmonious working of the Constitution for the sake of getting rid of an unacceptable president," said Iowa Republican James Grimes, who voted against impeachment. Johnson served out the remainder of his term as president, which amounted to another year.

The second president to be impeached, more than 100 years after Johnson, was Democrat Bill Clinton. This case is probably more familiar to most Americans, as Clinton allegations dominated headlines in the 1990s. Independent counsel Ken Starr alleged that President Clinton had lied under oath and obstructed justice in an attempt to cover up an affair with intern Monica Lewinsky and allegations of sexual harassment by Paula Jones.

In December 1998, the House voted to impeach Clinton for obstructing justice and committing perjury before a grand jury. The Senate trial began the following month and continued through February 1999. Neither of the two counts received enough votes to pass, and Clinton was acquitted.

Have Any Presidents Come Close to Impeachment?

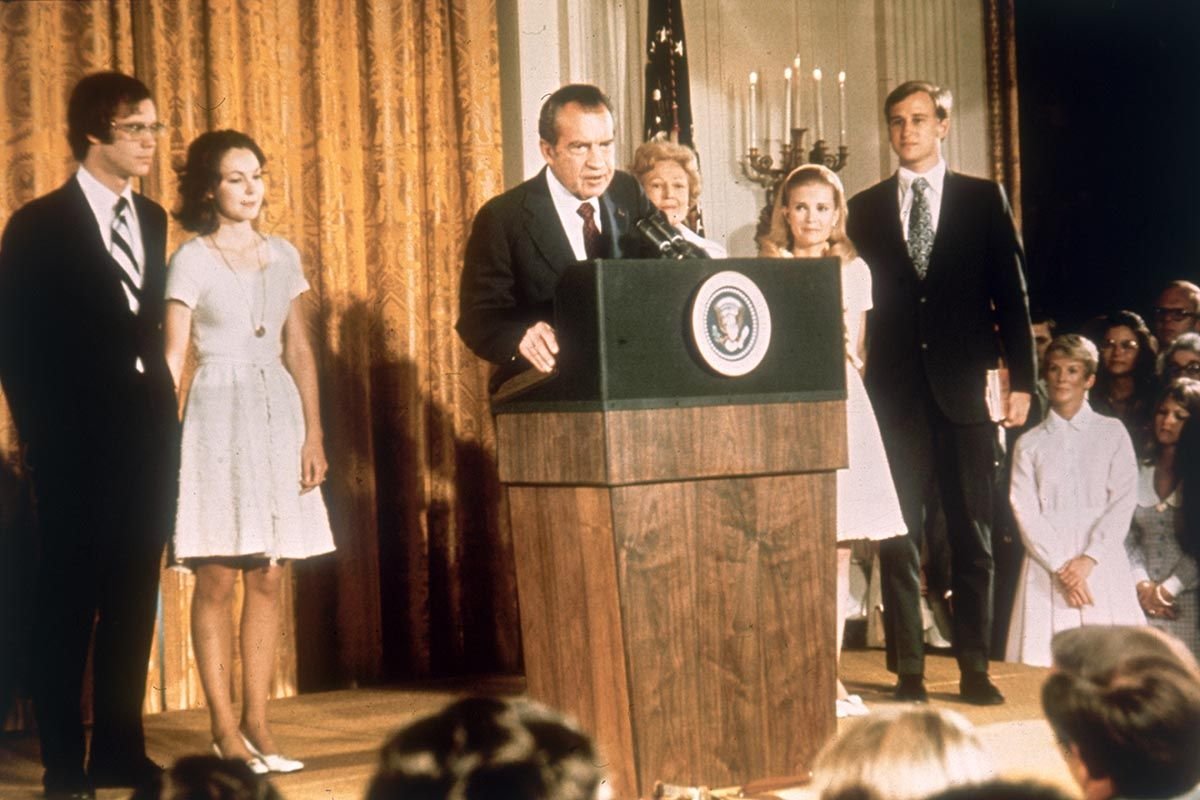

It's erroneously believed by many that Richard Nixon was impeached over his part in the Watergate scandal. Yes, the House Judiciary Committee opened formal impeachment hearings against Nixon in May 1974, during which Representative Barbara Jordan famously declared, "I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution."

Three of the five articles were approved by the Judiciary Committee in July 1974, accusing Nixon of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress. The articles of impeachment were due to be voted on by the full House and Nixon was preparing to fight the charges. But then the White House released the most incriminating tape recording yet, effectively ending the last vestiges of support for President Nixon.

On August 9, 1974, Nixon became only president in U.S. history to resign from office. The following month his successor, former Vice President Gerald Ford, pardoned Nixon for all his crimes.

At the dawn of this century, calls to impeach President George W. Bush saturated the news cycle. In 2008, 35 articles of impeachment were introduced to the House of Representatives, largely regarding his invasion of Iraq after 9/11. But Bush's second term came to an end before the articles were voted on, rendering the issue moot. His successor, Democrat Barack Obama, also faced calls for impeachment—for everything from failure to enforce immigration laws to claims he was born outside the U.S. But no articles of impeachment were ever submitted to the Judiciary Committee against Obama.

Can a President Be Removed Any Other Way?

The U.S Constitution does provide other routes to removing a sitting president: The 25th Amendment empowers the vice president to take over as acting president if faced with the "inability [of the President] to discharge the powers and duties." The clause isn't very specific—it's not clear who decides whether the president is able to discharge his powers. But it's largely used in situations where the president is temporarily incapacitated, like during surgery. The president's cabinet notifies Congress that the president cannot carry out his duties, and a two-thirds majority vote needed in both chambers to confirm the vice president as the acting president. A president can object to this process, giving Congress three weeks to decide if their ruling stands. In a situation like a temporary illness, it's likely that Congress would agree to reinstate the president once he had recovered.

In the 1980s, White House aides reportedly considered invoking the 25th amendment to remove President Ronald Reagan from office, worried he was in mental decline. Ultimately Reagan was deemed sound enough to finish his second term, although he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease five years after leaving the White House.

Like the process of impeachment, the grounds for invoking the 25th amendment are extremely subjective: Some may label President Donald Trump's behavior erratic or incompetent, but a case would have to be made for the marked deterioration of his abilities.

After all, these characteristics were on display before he was democratically elected president.

University of Arizona law professor Andrew Coan, author of Prosecuting the President says it's Trump's norm-smashing behavior that makes him far more resistant to nuanced constitutional law.

"The extreme polarization of American politics...means that every question is seen through a partisan lens," Coan told Newsweek. "It is very hard for the American people to impartially ask themselves, Has this president, in fact, committed criminal wrongdoing? When a president doesn't feel constrained by norms, it is much harder for special prosecutors to focus attention on these issues and for the public to judge the president impartially."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.