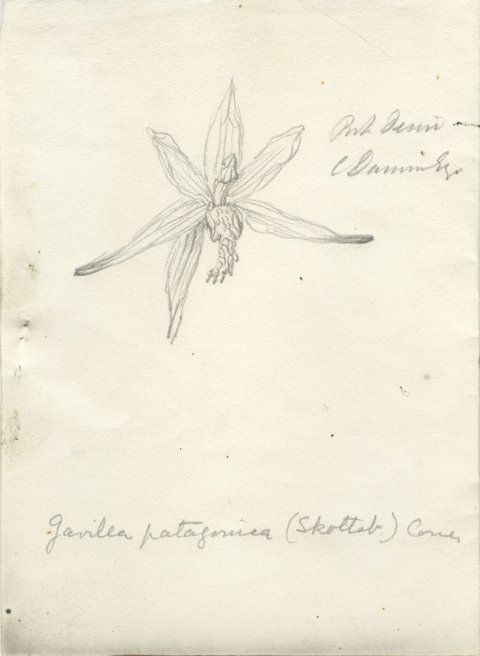

In 1833, a little more than a quarter-century before publishing On the Origin of Species, with the Beagle at anchor off the treeless shores of Port Desire, southern Argentina, Charles Darwin sat down and drew a flower. Just one flower, a not very good specimen of Gavilea patagonica, the foot-high orchid of temperate grassland that's a favorite fodder of the guanaco, the local cousin of the llama.

First, he blocked out the labellum, at the flower's procreational business end, with a heavy, thoughtful pencil line; next, with a lighter touch, he sketched the six streaky floral segments that surrounded it. It couldn't have taken him more than a few minutes. Then he attached the pressed flower to his sketch, signed his name and stored it ready to send back to England.

More than 180 years later, his sketch is about to be published for the first time, in Plant, a weighty new book that collects botanical art of all kinds, from a Minoan fresco of swallows billing among ocher red Lilium chalecondicum, painted circa 1600 B.C., to a hand-colored image from a scanning electron microscope of the seed of an alpine pincushion flower, its plum-colored skirts floating like a ballerina mid-jeté. These are things of beauty, but they have a purpose beyond decoration.

When Darwin took out his pencil, he didn't want just to draw the orchid. He wanted to know it. "Drawing is a very important way for a botanist to feel their way into a plant," says the British orchidologist Phil Cribb, who found the Darwin sketch 25 years ago, laid flat and shielded by sheets of protective paper, among the 7.5 million pressed and dried plant specimens stored by the Royal Botanic Gardens in its herbarium in Kew, London. Cribb describes the fireproof metal cabinets that line the herbarium as a "giant card index for identifying plants." The sketch's scientific utility is one reason he wouldn't let Kew's librarian remove it, "the kind of drawing I would do in a rush, in the field." Another might be a sense of brotherhood: "Botanists tend to be very fond of Darwin: Orchids were a passion for him."

Kew's curator of art eventually brought the sketch to the attention of Plant 's editors, but they don't confine themselves to the strictly scientific. A 17th-century copperplate engraving of an eyed garden poppy shows its several stages of development from tight-budded promise to fully open, feathery glory. It is printed opposite an Irving Penn photograph from 1968 of a dying stem of Oriental poppy, its drooped, tissue-paper head bowing to the inevitable.

Cribb, who says the specimen papers in the herbarium are filled with drawings from generations of botanists, annotating and counter-annotating in an argument expressed entirely in pencil lead, approves. "A really good artist," he says, "often sees things a botanist misses. We look at a plant thinking we know what to expect; they look at it with their eyes open."

Plant: Exploring the Botanical World is published by Phaidon, £40 ($51)