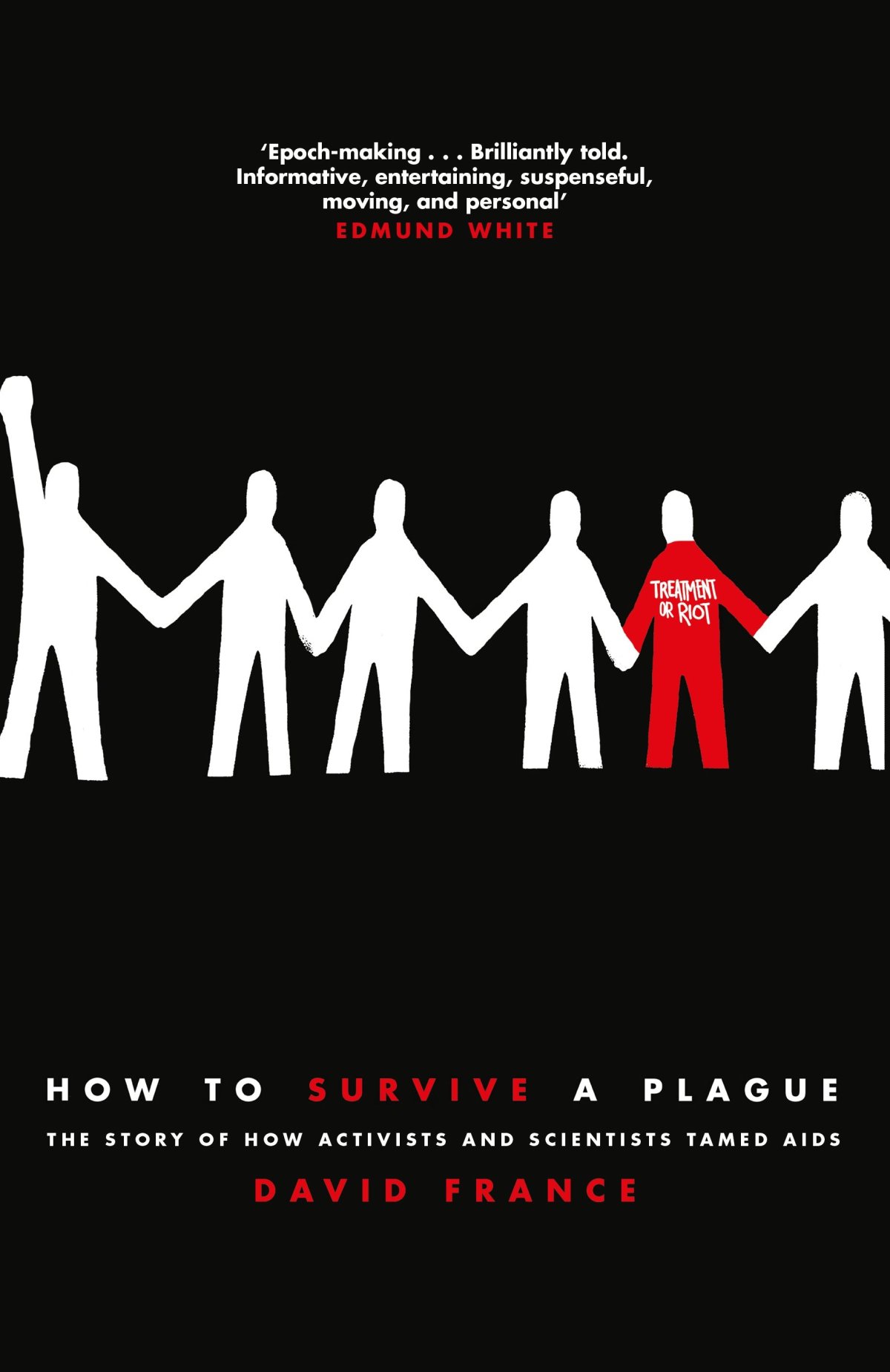

The edited extract below is taken from How to Survive a Plague by David France, shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize 2017.

How to Survive a Plague is the riveting and powerful story of the AIDS epidemic and the grassroots movement of activists who grabbed the reins of scientific research to help develop the drugs that turned HIV from a mostly fatal infection into a manageable disease. France, a chronicler of AIDS from the earliest days, uses his unparalleled access to the community to illuminate the lives of dozens of extraordinary characters.

The doors swung open at precisely 2.30 p.m. The mood inside was mostly somber and reflective, despite the efforts of a pair of drag queens done up as Joan Crawford and Cox's totem, Bette Davis, greeting the mourners. A video played scenes from the old films that always ran through Cox's mind and frequently spilled from his lips. The camp sensibility was lost on almost nobody except perhaps for Cox's mother, Beverly, who had traveled up from Atlanta. She steadied herself on the arm of Nick Cox, Spencer's only sibling, who was also gay. They took seats in the first row, alongside friends of the family. A mother's grief was a thick wall around them.

When Larry Kramer arrived, one of the organizers took him by the arm. "Follow me, I have a seat for you," he said, leading him through the crowd to the second row. Among the activists, Kramer alone was accorded this special treatment. No individual was more responsible for galvanizing the AIDS movement than Kramer. His plays, books, and essays over the years pushed the gay community to demand that the world take notice. Now seventy-seven, he stayed as busy as ever, though AIDS had slowed him noticeably and he too felt a touch of the survivor's syndrome. That morning he seriously considered not coming. What finally motivated him to take a cab uptown was a need to stand with his fellow survivors, for whom his emotions were boundless. "Love was always love, anytime and anyplace," Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote, "but it was more solid the closer it came to death."

Chip Duckett, a professional party planner who had organized the affair, walked to center stage to begin the service. "If there was ever any question that Spencer Cox would stop at absolutely nothing to be at the center of attention"—he broke for over-eager laughter—"this is it."

He passed the microphone to a succession of speakers, eventually introducing Mike Isbell, Cox's partner for more than eight years. After their breakup they had remained friends for many years, but as he had with so many people, Cox pushed Isbell away as his troubles grew. They hadn't spoken in some time. "Spencer often didn't make it easy for people who loved him," Isbell began. "The AIDS epidemic traumatized Spencer, and I imagine this trauma stayed with him until the end. I recall being at dinner parties—some of you were probably there—or out to meals with friends, where someone would talk about 'living with AIDS' and Spencer would immediately reply, 'I'm not living with AIDS, I'm dying of AIDS!' He'd say this in a tone of defiance, but I knew he was scared to death."

Isbell spoke of how ironic it was that Spencer lost his way after the treatments arrived and the lifesaving mission came to an end. "He desperately wanted another life outside of AIDS," he said, looking around the overflowing room. "It seemed that in the 'treatment era,' he was always in search of something but not finding it."

Peter Staley was the last to speak. He had been unable to sleep the previous few nights, struggling to find the words to make sense of Cox's death and life. Staley was among a small group of people who had raced to Cox's side when they'd learned about the final hospitalization. By the time he arrived, Cox was already in steep decline. He'd gone into cardiac arrest three times, and his kidneys had failed. Staley stood outside the hospital door as medical personnel rushed in and out. He could hear the defibrillator lifting Cox's chest off the table again and again. When Cox was stabilized, Staley and Tim Horn, another activist, were allowed inside briefly. Minutes later came another heart attack and another brutal resuscitation.

From his telephone, Staley posted a note to a private Facebook message group where he'd been coordinating support for Cox. It landed in my phone with a vibration and a jingle as I stood in the cold morning sun on Sixth Avenue, a mile and a half away: Spencer passed. I slumped, lightheaded and bereft, against a plate glass window.

The four weeks between then and the memorial service had done little to dim Staley's pain. He placed the pages of his planned eulogy on the small lectern, squinting into the harsh stage lighting to study the faces before him.

He said, "I first met Spencer when he started showing up at ACT UP meetings in the fall of '88. We were all so young. I was younger than most. But he was seven years my junior."

He caught his breath, remembering.

"It was a wonder watching him wow the FDA, and in meetings with the biggest names in AIDS research, like Anthony Fauci. He earned the respect and the love of his fellow science geeks and those of us lower down the learning curve… Eight million on standardized regimens. Eight million lives saved. It's a stunning legacy, and so bittersweet. How could that young gay man, confronted with his own demise, respond with a level of genius that impacted millions of lives but failed to save his own?"

Staley spoke of Cox's last failed burst of activism, and called on the weathered activists to snatch meaning from his death. "He spoke out forcefully about the depression and PTSD that the surviving generation of gay men from the plague years often suffered from, regardless of HIV status. While many of us, through luck or circumstance, have landed on our feet, all of us, in some way, have unprocessed grief, or guilt, or an overwhelming sense of abandonment from a community that turned its back on us and increasingly stigmatized us, all in an attempt to pretend that AIDS wasn't a problem anymore."

He scanned the vacuum-quiet room. "That is Spencer's call to action," he said, "and we should take it on."

How to Survive a Plague is published by Picador (£25 hardback; £19.99 ebook).

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.