Fifty is the gateway to the most liberating passage in a woman's life. Children are making test flights out of the nest. Parents are expected to be roaming in their RVs or sending postcards of themselves riding camels. Free at last! Women can graduate from the precarious balancing act between parenting and pursuit of a career. Time to pursue your passion. Climb mountains. Run rapids. Rediscover romance. You have a whole Second Adulthood ahead of you!

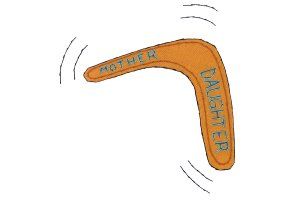

That has been the message of my books since I wrote New Passages 15 years ago. What I didn't see coming was the Boomerang.

With parents living routinely into their 90s, a second round of caregiving has become a predictable crisis for women in midlife. Nearly 50 million Americans are taking care of an adult who used to be independent. Yes, men represent about one third of family caregivers, but their participation is often at a distance and administrative. Women do most of the hands-on care. The average family caregiver today is a 48-year-old woman who still has at least one child at home and holds down a paying job.

It starts with The Call. It's a call about a fall. Your mom has had a stroke. Or it's a call about your dad—he's run a red light and hit someone, again, but how are you ever going to persuade him to stop driving? Or your husband's doctor calls with news that your partner is reluctant to tell you: it's cancer.

When that call came to me, I froze. The shock plunges you into a whirlpool of fear, denial, and feverish act-ion. You search out doctors. They don't agree on the diagnosis. You scavenge the Internet. The side effects freak you out. You call your brother or sister, hoping for help. Old rivalries flare up. You haunt the corridors of the hospital, always on duty to prevent mistakes.

It begins to dawn on you that your life is also radically changing. This is a caregiving role that nobody applies for. You don't expect it. You aren't trained for it. And, of course, you won't be paid for it. You probably won't even identify yourself as a caregiver. So many women tell me, "It's just what we do."

We'd like to think that siblings would be natural allies when parents falter. In countless of my interviews with family caregivers, I hear the same stories: Brothers bury their heads in the sand. The farther away a sister lives, the more certain she will call the primary caregiver and tell her she doesn't know what she's doing. A major 1996 study by Cornell and Louisiana State universities concluded that siblings are not just inherent rivals, but the greatest source of stress between human beings.

There are many rewards in giving back to a loved one. And the short-term stress of mobilizing against the initial crisis jump-starts the body's positive responses. But this role is not a sprint. It usually turns into a marathon, averaging almost five years. Demands intensify. Half of family caregivers work full time. Attention deficit is constant. But most solitary caregivers who call hotlines like Family Caregiver Alliance wait until the third or fourth year before sending out the desperate cry: "I can't do this anymore!"

The hypervigilant caregiver becomes exhausted, but can't sleep. Chronic stress turns on a steady flow of cortisol. Too much cortisol shuts down the immune-cell response, leaving one less able to ward off infection. Many recent clinical studies show that long-term caregivers are at high risk for sleep deprivation, immune-system deficiency, depression, chronic anxiety, loss of concentration, and premature death.

Ailing elders seldom say thank you. On the contrary, they often put up fierce resistance to the caregiver's efforts. "A major component of psychological stress that promotes later physical illness is not being appreciated for one's devoted work," explains Dr. Esther Sternberg, a stress researcher and author of The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. She places caregivers at the same risk for burnout as nurses, teachers, and air-traffic controllers.

Once the solitary caregiver gets so stressed out emotionally that her own health declines, she can no longer provide the care. The only option left is to place the family member in a nursing home—the last choice of everybody, the most expensive for taxpayers, and guaranteed to leave the caregiver burdened with guilt.

It doesn't have to be this way. From hundreds of interviews with caregivers and my own experience of 17 years in the role, I can suggest some survival strategies:

Ideally, have the conversation with your siblings before the crisis with Mom and Dad. Make it clear that you cannot do this alone. If the crisis is already upon you, hold a family meeting—in -person—but don't set yourself up as the boss. Ask a neutral professional—your parent's primary doctor or a social-worker—to act as mediator. Everyone will be informed of the diagnosis and care plan at the same time. Ask your siblings to come prepared with "What I can do best…" One may contribute money, another has more free time. Everyone has to feel valued.

Download a free Internet-based care calendar that is totally private and can function as the family's secretary, coordinating dates and tasks to be shared.

Join a support group. Learn from veteran caregivers, who are eager to offer practical short-cuts and know instinctively what you need emotionally. Regular exercise is vital to break the cycle of hy-pervigilance and prepare the body for more refreshing sleep. Ask for appointments for your physical checkups or tests at the same time and place where you take your family member.

You must take at least one hour a day—but every day—to do something that gives you pleasure and refreshment. Have a manicure. Take a swim. Call a friend for coffee. Window-shop. Try a yoga class. All this allows your nervous system to reset.

You will also need longer breaks every few months. Call your local Area Agency on Aging and ask where you can take your family member for a respite stay. Rehab facilities often have some beds for the purpose. Under Medicaid, the caregiver is entitled to three or four days away every 90 days.

Above all, do not fall into the trap of Playing God. When the devoted caregiver comes to believe that she is responsible for saving a loved one's life—often reinforced by the care-recipient—any downturn will feel like a personal failure. It's not. No mere human can control disease or aging.

When it becomes clear that your loved one does not have long to live, the caregiver who survives must begin the effort of coming back to life. There is peril in remaining so attached to your declining loved one that you lose your "self." Palliative care or hospice is invaluable to support and advise you on how to pace yourself at this stage. Medicare or Medicaid will pay for a home health aide to stay with your loved one.

This is the time to replenish your emotional attachments. Reach out for old friends, grandchildren, your church or temple. Take a class at the local Y or community college. Join a book club or a baseball league. I know, I know, you're too tired. But meeting new people is a natural antidote to late-stage caregiving. New attachments are a bridge to your new life.

You will be answering one of the most profound questions that trouble the dying: what will become of you when I leave you? To see the caregiver joyful again can be a gift of relief.

Sheehy is author of 16 books. Her most recent, Passages in Caregiving: Turning Chaos Into Confidence, was published in May.

Healthy Living: The Complete Package

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.