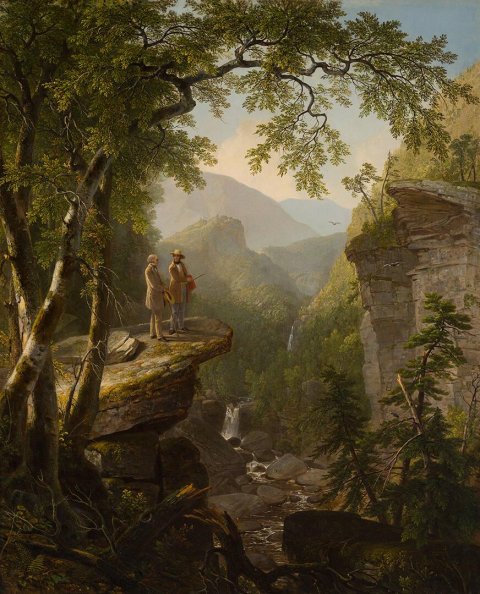

Almost ten years ago—Nov. 11, 2011 to be exact—Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened its doors. The spotlight was immediately bright. It was the first major league museum built in the U.S in decades and the founder, Walmart heir Alice Walton and the family's foundation, poured hundreds of millions into the building, designed by super architect Moshe Safdie, as well as the collection. One of the more striking examples: The $35 million-plus Walton paid, or some say overpaid, the New York Public Library for the Hudson River landscape, Kindred Spirits, by Asher Durand, a record at the time for an American painting. You, and everyone else, could also see Kindred Spirits for free thanks to Walmart.

The new museum also got a lot of notice because of its location. Northwest Arkansas may be the home of the biggest company in the world, but it's never been an American cultural center. As far as most of the art world was concerned, Bentonville was literally in the middle of nowhere and Alice Walton was a super-rich art enthusiast trying to buy into the big leagues.

Now, the museum is not only an internationally respected institution it's also, by the numbers, a success. Despite the location, patrons have knocked down the doors. And starting July 11, the museum celebrates its 10th anniversary with the "Crystal Bridges at 10" exhibition. "We knew there was support for a cultural institution in the heartland, but I was surprised and encouraged by the number of people who embraced the museum immediately," Alice Walton tells Newsweek via email. "By the end of our first year, our attendance was 650,000—more than double our projection." Since the opening, she adds, "5.3 million people have visited from every state in the country and across the world."

Not only that, Crystal Bridges has developed, by design, a diverse collection— heavy on works by contemporary women and minority artists like Amy Sherald, Rashid Johnson and Nari Ward, not just long-gone white guys. (Almost half the works in the contemporary art galleries are by artists of color.)

As art critic Philip Kennicott wrote in The Washington Post in 2018: Crystal Bridges "has established itself with more gravitas than other museums that have been fashioned, ex nihilo, from the gleaming lucre of a single wealthy person."

I'm not an art expert or even much of an educated fan. Still, I like the museum a lot, as I do its sister arts and performance space, The Momentary, from their beautiful designs and settings to the spacious galleries to the thought-provoking exhibitions. I've been back twice and will return a third time once it completes a major expansion by 2024 or so. It is a bucket list-level attraction.

It is also loudly and proudly, as The Washington Post once said, "woke."

On a visit to the museum's web site, I found, along with the hours of operation and Crystal Bridges earrings, a slew of social justice declarations ranging from support for Black Lives Matter to the launch of a provocative current events series called "In Real Time" to having the back of the trans community when Arkansas state lawmakers passed anti-LGBTQ legislation. Some examples:

On the Jan. 6 insurrection in Washington, D.C.: "The symbols of racism brandished by the rioters and the artwork honoring problematic historical figures inside the Capitol building were chilling reminders that there is still much work ahead of us...the first step is to honor our commitment to being an antiracist institution and call out discrimination, injustice, and white supremacy when we see it."

On Black Lives Matters: "We can't naively think that the same prejudices and privileges currently shining a spotlight on Minneapolis, Atlanta and other areas don't exist here in Northwest Arkansas."

On a new Arkansas law restricting gender affirming treatments for trans kids: "In light of the recent legislation...we share our support for all LGBTQ+ people as a valued and respected part of our community."

Rod Bigelow, the museum's long-time executive director and chief diversity & inclusion officer says the announcement was a tad "late," but, still, a great example of the staff and the museum's leadership jumping into the fray on a controversial equality issue in their own backyard.

How did a museum in an ultra-red state—and a congressional district that hasn't elected a Democrat since A Hard Day's Night hit screens—get into the business of social justice? Arkansas doesn't just lean right, it is a state represented in Congress by Senator Tom Cotton who recently filed a tax bill to punish colleges such as Harvard and Stanford for teaching "un-American ideas" like critical race theory.

Nonetheless, Alice Walton says, "The museum was founded with a mission to welcome all and that's guided us since day one."

I've been to Northwest Arkansas a few times over the years and have always enjoyed my visits there. Back in the 1980s, as a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, I covered the young Walmart before people started blaming it and founder, Sam Walton, for destroying small town America's picturesque downtowns, some of which had never existed anywhere but in our imaginations. Bentonville, obviously, has changed a lot since then. On my first trips here, I, on occasion, stayed in motels with Gideon Bibles inside creaky bedside tables along with instructions about what to do in case of a tornado. When I visited this May I stayed at the Aloft, a contemporary hotel with fashion-first rooms. Bentonville now has its own, designer-downtown with all the trendy restaurants and shops that go along with it. (Kind of ironic if you think about it.)

But some things haven't changed.

If you are any shade of blue, you might want to proceed with some caution here. As in many places in the South, and I've lived in a few, think twice before talking about anything more serious than SEC football. Arkansas did, after all, deliver almost 30 percentage points more votes to Trump than Joe Biden. Recently, according to the U.K. newspaper The Guardian, a yearbook at a Bentonville middle school had photo captions referring to Black Lives Matters protesters as "rioters" and insisting "President Trump, WAS NOT impeached." And if that's not enough, former Trump flack Sarah Huckabee Sanders is a candidate for governor. The state flag also celebrates Arkansas' membership in the confederacy.

So how did liberalism or wokeness or whatever you want to call it evolve at Crystal Bridges? Folks I talked to at the museum say it was part of Alice's original thinking to be a safe place for all patrons: Blacks, Whites, Gays, Straights, Asians, Hispanics...everyone. So that kind of explains it.

But four years after the doors opened, something else happened that served as a wake-up call for Crystal Bridges in particular and the museum and arts business world in general. In 2015, the Andrew Mellon Foundation and the Association of Art Museum Directors released a study that showed that museums were really, really, white places in terms of staffing— more than 70 percent non-Hispanic white. It is not entirely clear if Crystal Bridges management at that point had an epiphany that they weren't as "open to all" as they thought they were. No one at Crystal Bridges I talked to would quite put it that way. But the Mellon report clearly struck a chord with the board. In 2016, after the Mellon report came out, only 11 percent of the staff at Crystal Bridges identified as "diverse," according to the museum. (The current number: 28 percent.)

"Seeing the data created a moment of clarity about our path forward," Walton says, "We took a closer look at who we were as a museum just four years old and realized we needed to do better if we were truly focused on fulfilling our mission."

The board decided to take a look at itself, at its staff and even the collection. 'Chief diversity & inclusion officer" was added to exec director Bigelow's title. "We knew we could do more," he recalls. "It was then that the board made a commitment to diversify and adopted a strategic priority to be an anti-racist institution."

The numbers show the changes. In the contemporary art galleries, 48 percent of the works are by artists of color and 53 percent by women. In terms of acquisitions, 18 percent of the pieces were categorized by Crystal Bridges as "racially/ethnically" diverse in 2015 compared to 71 percent in 2020.

In any event, the proof of wokeness is not only in the numbers but also in the eye test.

Depending on when you visit, you may see the "greatest hits," as chief curator Austen Barron Bailly calls them, like Norman Rockwell's 1943 Rosie the Riveter and the aforementioned Kindred Spirits. Edward Hopper, Thomas Hart Benton and John Singer Sargent are there, too. But a walk through the museum will also show you something very different. The opener to the early American art galleries is a massive work by Nari Ward called We the People. Its accompanying commentary points out that "the guiding ideals and aspirations outlined within" the preamble to the United States Constitution "excluded many—essentially guaranteeing equality and rights only to white men." An exhibit on black churches has an historic map of key events including the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, which just marked its 100th anniversary, and the 2015 church murders in Charleston.

"We are very intentional with our words and our interpretive approaches and are not afraid to burst a bubble," explains Barron Bailly. A 2020 exhibition "Ansel Adams: In Our Time" featured this comment from an "interpretive panel" to its display of the photographer's iconic landscapes: "While Ansel Adams and his images helped create a general sense of pride in our national parks, not all Americans feel welcome in these outdoor spaces."

Even the museum gift shop continues the message that this is a place that welcomes everyone. For example: children's books for sale include the legendary Tar Beach by Faith Ringgold, The Youngest Marcher by Audrey Faye Hendricks and From Cotton to Silk: The Magic of Black Hair by Crystal C. Mercer.

In addition, the staff is given a lot of latitude to weigh in not only on the collection, but also on the museum's public declarations as well. Statements on Black Lives Matters, for instance, were initiated "with support of the board," says spokesperson Beth Bobbitt, by the staff and top brass such as Bigelow. Another example of the museum empowering its staff: At the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Allison Glenn, Crystal Bridges' associate curator of contemporary art, was recently guest curator for "Promise, Witness, Remembrance," an exhibit on the life of Breonna Taylor, killed by police during a raid on her home. Glenn says there was never any doubt she was going to work on the exhibition even though it wasn't part of her Crystal Bridges portfolio. "It's something I just had to do," says Glenn who will soon take a position at the Contemporary Art Museum of Houston, but finish up projects at Crystal Bridges. (Glenn, a rising star, says Bobbitt, "can't be contained in one museum.")

Has there been any backlash from conservatives?

Some for sure, but not a tsunami of criticism. The worst perhaps came from the conservative National Review's art critic Brian T. Allen, who is actually a fan of the museum. A sample: "Crystal Bridges, a great museum, should ditch the preachy wall panels, let the art speak for itself—and let the visitors think for themselves."

And sometimes the art itself, and the mission, speak too loudly for some local audiences.

Consider "Men of Steel, Women of Wonder," Crystal Bridges curator Alejo Benedetti's celebration of comic book art that "delves into many issues in contemporary life: race, immigration, sexism, gender and human frailty..." The exhibition featured Between the Capes, a painting by Rich Simmons showing Batman and Superman sharing a decidedly non-Platonic kiss and a video by Sarah Hill about a transgender Wonder Woman. Beth Bobbitt says "there were field trips cancelled after a (local) school district learned" about the superhero embrace. "The school tour didn't include this artwork as one of the tour stops, but it was upsetting to some parents nonetheless."

While a quick scan of Crystal Bridges' Facebook page features mostly positive comments, some of the more unprogressive patrons are certainly taking notice of the social justice advocacy. And they are not at all that, well, nice. When the museum announced plans to celebrate Gay Pride Month by featuring works of LGBTQ+ artists like Robert Indiana and Martine Gutierrez, one Facebooker responded: "You are no longer on my bucket list...if you support LGBTQ." Another comment triggered by the museum's support of BLM: "Left wing groups like Black Lives Matter and (the) media have us believing there is systemic racism."

But all that aside, Crystal Bridges and Alice Walton have managed to do what they said they were going to do when launched in 2011: build a world-class museum with a diverse collection, open its doors to everyone who stops by and take a stand on some of the big social justice issues of our time. And the customers keep on coming. In pre-COVID 2019, for example, 702,000 people passed through its doors compared with 506,000 in 2013.

No one, now, questions that Walton and her museum are playing, and quite well at that, in the major leagues.

-

Hank Gilman is a senior-editor-at-large at Newsweek. He has also worked at The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe and Fortune as that magazine's deputy editor. Gilman is also the author of You Can't Fire Everyone, a management memoir. He's not sure that's true these days, however.