It was a memorable, violent day in lower Manhattan. No, not that day—but another.

In early May 1970, America was bitterly divided about everything from hot pants to Ho Chi Minh, but especially the Nixon administration's bombing of Cambodia, which escalated and expanded the Vietnam War. On May 4, four students protesting the invasion were killed by National Guardsmen during a demonstration at Kent State University in Ohio.

New York's mayor, John Lindsay, sharing the sadness and outrage of many Americans, ordered flags at City Hall to be flown at half-staff. In lower Manhattan, antiwar demonstrators marched peacefully.

Construction union leaders, who were zealous backers of Nixon's Vietnam policies, organized a counterprotest. Workers—or "hard hats," as they were known—left their girders and skyscrapers with their clenched fists held high and hit the streets with "America: Love It or Leave It" placards, and shouts of "Kill the Commie."

Breaking through a police barricade, the construction workers pummeled, kicked and bashed the protesters, seeking out, one witness reported, the men with the longest hair. Not satisfied with knocking around longhairs, the workers stormed City Hall to try to get the flag raised to full staff. Frightened City Hall staff raised the flag while hard hats screamed at the "red mayor."

Today the "Hard Hat Riot" is little remembered, but at the time it marked an important chapter in the long, painful estrangement between working-class white men and the Democratic Party. This relationship plays a central role in where the country is now and where it's heading in this fall's midterm elections.

Democrats Are Nervous

Working-class white men used to go with the Democratic Party like hot dogs and mustard. And now? Well, not so much. The complex political allegiances of noncollege voters—and particularly noncollege white men—get less attention than the rise of the Hispanic voter. The white working-class percentage of the electorate may be on the decline, but white working-class men remain a voting bloc neither party can afford to ignore.

Democrats have assembled a "Coalition of the Ascendant"—Hispanics, African-Americans, affluent white voters (especially women) and millennials—that has twice given Barack Obama the presidency. And his policies, from gay marriage and government regulation of the coal industry to opening doors to immigrants, have helped cement that coalition.

Indeed, the two biggest Supreme Court cases of the past two years involved the Obama administration fighting laws on behalf of that coalition—laws that President Bill Clinton enthusiastically signed: the Defense of Marriage Act and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which were at the heart of the gay marriage and Hobby Lobby cases. White noncollege voters aren't all cultural conservatives, but they often lean that way—and Obama's progressive politics have pushed them further away from the Democrats.

The estrangement has had touchstone after touchstone. There was the Silent Majority Richard Nixon courted in the 1960s (as opposed to what he thought of as loud-mouthed liberals).

One cultural marker was All in the Family in the 1970s, the No. 1–rated TV show about an outer-borough New York bigot wrestling with rapid changes in society. Archie Bunker's sentiments echoed the white working-class preoccupations of the time, as did the blue-collar anti-busing protests in Boston.

In the 1980s, the issues of income taxes, high crime rates and devotion to the military led to the rise of the Ronald Reagan Democrats—white working-class families, often ethnic and Catholic, who were prepared to abandon the party of their parents and grandparents.

In the 1990s, despite Clinton's success at reaching some of these lost Democratic voters, their drift rightward continued, with angry white men fueling the 1994 Newt Gingrich small government–low taxes revolution, a year after Newsweek ran a cover story on "White Male Paranoia."

Since 2000, white working-class men have become so estranged from the party of the New Deal that in some states Obama won only 10 percent of their vote. (Overall, about a third of white working-class men gave Obama their support.)

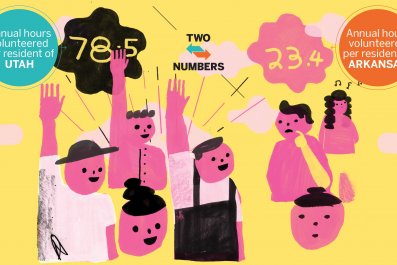

And it's not all racial. Democratic presidential candidates Al Gore, John Kerry and Obama each saw competitive or even Democratic states with lots of working-class whites—such as Arkansas and West Virginia—go into the Republican column. In 1994 and 2010, Republicans took back the House of Representatives in landslides in large part because white male working-class voters deserted the Democrats.

In 2010, for instance, success in rust belts in Ohio and Pennsylvania and in the rural South, among other regions, drove the Republicans who took the House from then Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats. In the 2012 election, Obama attracted fewer white voters than any Democratic candidate since the 1960s. And in the subset of working-class white men, he lost by a 31-point margin. But because noncollege whites have become an ever smaller part of the pie, Obama was able to win the election. Noncollege whites of both sexes constituted half of Clinton's electoral strength in 1992, but made up only a quarter of Obama's support in 2012.

This year the impact of white working-class voters looks likely to be amplified. In presidential voting years, minority voters come out in bigger numbers, diluting the impact of white working-class voters who may constitute a third of the electorate in an off year but only a quarter in a presidential election year.

That's why so many Democrats are nervous about this fall.

A Sense of Aggrievement

If the prospect of higher white-working-class turnout wasn't bad enough for Democrats this fall, the Senate battleground states—Louisiana, Montana, Kentucky, Arkansas, West Virginia, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Iowa, and Michigan—are thick with working-class whites. In West Virginia, a state so Democratic it went for President Jimmy Carter in the Reagan landslide of 1980, the Senate seat held by Jay Rockefeller is certain to go Republican, while a veteran Democratic House member, Nick Rahall, will be lucky to hang on to his seat, despite spending the past 20 years in Congress. Rahall is attacking the Koch brothers and "New York City money" to stay competitive—and that may not be enough.

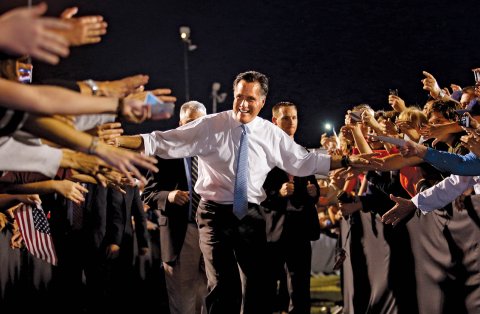

For Republicans, the stakes are also high this fall. As minorities become an increasingly powerful part of the electorate, especially Democratic-leaning Hispanics, who gave 71 percent of their vote to Obama in 2012, working-class white men are losing clout. (Mitt Romney attracted a larger percentage of the white vote than Reagan did in 1980, but because the percentage of whites in the overall electorate has gone down, Obama became the first president since Dwight Eisenhower to win two elections with more than 51 percent of the popular vote.)

Even as Republicans solidify their hold on noncollege white men, they can't rely on them in perpetuity. And in some states, especially in the upper Midwest and Northeast, Democrats have reduced their losses to the point where they can win states like Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania because they lose noncollege white voters by a smaller margin.

Political consultants of both parties are watching what issues will form the tableau of the election and how they might affect differing groups, including noncollege white men. One of them is immigration, which the president may take up through executive action. Democrats are betting that it's a plus for them, wooing Hispanics, even if it might play poorly with working-class white men.

The strife in Ferguson, Missouri, could be an electoral wild card this fall for both parties. After an August that saw the shooting of an unarmed black teenager at the hands of a white police officer, the St. Louis suburb became a focus for national anger—a combustible mix of race, poverty, police militarization, voting rights and a slew of other issues. By month's end, the violence seemed more tempered following a funeral service for the dead young man, Michael Brown.

But autumn presents the possibility of more controversy, if not violence. The St. Louis County district attorney says he could be presenting evidence in the case to a grand jury through mid-October, putting the possibility of an indictment in the shooting of Brown—or lack of one—right in the middle of the midterms. How an indictment or continued civil unrest might affect different electoral groups is anyone's guess, but it's worth noting that in an August poll by the Pew Research Center, noncollege white men—more than any other racial group—said too big a deal was being made of race in the case.

The story of what makes white working-class men vote and in which direction is a complex one. They're not monolithic by region or religion. And it's not easy to measure them by occupation either, so pollsters use the index that's easiest to measure and less prone to error, even though it's less than perfect: whether they went to college.

While this might conjure up the image of a construction or factory worker, these days most noncollege white males are more likely to be found in low-end office jobs or in retail sales as cashiers—two of the fastest growing job categories in America. But what a disproportionate number of noncollege white men seem to have in common, according to polls, is a profound sense of aggrievement—at the rich for rigging the system and the poor for getting benefits they don't deserve.

In one survey, working-class men were given this choice for describing the poor:

A. they have a hard life;

B. an easy life.

Nationally, about 44 percent said the poor had it easy, and 47 percent said they had it hard. But among noncollege white men it was 56 percent easy and 30 percent hard.

When asked whether government should do more to solve national problems or leave more to individuals to decide, Americans overall split, 45 percent in favor of more government intervention to 51 percent against. By contrast, a full 62 percent of white working-class men said government should do less.

"You look across the board and they're outliers. That is really powerful, and once their income started declining, they became very receptive to Republican arguments that [the government was] taking your money and giving it to others," says Ronald Brownstein of Atlantic Media, an expert in white working-class voting who mined the data and used the results of a Pew poll in June.

That sense of aggrievement also has a cultural element. Today it's socially acceptable to poke fun at "white men" or "white guys." For working-class white men who have seen their wages and wealth drop as the economy has come to value "brain" workers more than manual laborers, there's no feeling of white privilege, even if their lot is far better than being a minority in poverty. Indeed, with women now more likely to enter and finish college than men, and enjoying better health and longer life expectancy, the frustration of poorly educated white men is understandable.

"If you're a white male and you don't have a college degree, you're struggling and frustrated; and often you're not going to blame yourself," says Ed Sarpolus, a nonpartisan pollster in Michigan who has studied working-class voters.

"No group has declined more in standing," notes John Lapin of the Center for American Progress, who has studied the working-class vote. Indeed, the white poverty rate is accelerating much faster than the minority poverty rate, and the white working class is among the most pessimistic groups in the country—more even than poor blacks or poor Hispanics.

Declining Union Membership

The steady working-class journey to the right has been well chronicled—racially tinged complaints about crime, affirmative action and the role of government, along with wariness of social liberalism on issues like gay rights, gun control and a general weakening of traditional authority. In 1985, Jonathan Rieder wrote Canarsie: The Italians and Jews of Brooklyn Against Liberalism, that showed how urban ethnics—more than a decade after the Hard Hat Riot—turned their back on a liberalism they thought coddled criminals and had nothing to offer hardworking people like them.

And 10 years ago, Thomas Frank's What's the Matter With Kansas? suggested that working-class folk were voting against their pocketbook issues—duped, the liberal author declared, by Republican pitches on guns, God and gays.

But working-class whites are not the same as they were even 10 years ago. With family breakup accelerating, they're more likely to live in single-parent households and have out-of-wedlock births at rates higher than in 1965, when Daniel Patrick Moynihan, later a U.S. senator, issued The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, his controversial report about the breakup of black families.

And there are important regional differences. Working-class whites in the South are much more estranged from the Democratic Party. In Alabama, Obama got only 11 percent of the noncollege white vote and 10 percent in Mississippi. In Ohio, less fundamentalist and more unionized, Obama was able to pull about 42 percent of the vote of noncollege whites and 43 percent in Pennsylvania, which isn't ideal for Democrats but is enough—combined with their other loyal groups—to win elections. An even closer parsing of data shows how the collapse of Democratic support among white working-class voters extends beyond the South to the mountain West and Plains States. The president garnered a majority in Maine and Vermont. (If only white men could vote nationwide, Obama would have won just Maine, Vermont, Massachusetts, Oregon and Washington.)

The question of how to reach these voters in an age of declining union membership is a tough one for Democrats. The AFL-CIO's Working America initiative has had considerable success going door to door and engaging voters the old-fashioned way. "Face-to-face visits are painstaking. We ring the doorbell, and a third aren't interested. But two-thirds are, and we become a source of information for them that they're not getting," says Karen Nussbaum, who heads the group.

One thing that has helped Democrats and Republicans is having leaders who can speak directly to these voters. George W. Bush and Bill Clinton had that valuable skill; Obama has had missteps. There was, for instance, his caught-on-tape moment in San Francisco about how the working class clings to "their God and guns."

And there was his query in Iowa that made him seem out of touch with ordinary working Americans: "Anybody gone into Whole Foods lately and see what they charge for arugula?" he asked. "I mean, they're charging a lot of money for this stuff."

Conservatives and the media pounced, while Obama defenders argued that Iowans grow arugula and you can buy it anywhere in the U.S. Still, it was reminiscent of Michael Dukakis encouraging hard-strapped Iowa farmers to grow Belgian endive.

But Republicans can get it terribly wrong, too. Romney's remarks, caught on video, denouncing 47 percent of the country as loafers and cadgers seemed to be proof he didn't understand a key demographic that's struggling.

Romney's gains among white working-class voters were with white working-class men. John McCain's edge among them in 2008 was 59 percent to 39 percent, which Romney upped that to 64 percent to 33 percent.

But Romney's advantage among white working-class women was 20 points, up only three points from McCain's 17-point margin in 2008. Romney's failure to garner white working-class women was part of why he lost.

The greatest opportunities for Democrats to regain the initiative with white working-class men will probably come with a more full-throated economic message—one less about fairness, which working-class white men are more likely to see as a giveaway to the poor, and more about helping them recover their dignity, whether it's through defending old-school entitlements like Social Security and Medicare or taking a tougher stance on the wolves of Wall Street.

The big question is how Hillary Clinton might fare with these voters, should she run for president in 2016. There are some indicators in her favor. She's part of a Clinton brand that won two presidential elections in part by minimizing the loss of noncollege white men. And in 2008 she trounced Obama among working-class whites in Democratic primaries—allowing her to rack up victories in West Virginia, Oklahoma and elsewhere. Whether the narrow pool of Democratic primary voters will prove representative of voters as a whole is a question that will occupy Democratic strategists between now and 2016.

Still, staffers in Hillaryland had a saying that, among women, you could tell a (white) Hillary voter by her shoes, specifically whether they're worn out from standing much of the day, as would be those belonging to a waitress, a teacher or a nurse. But a new Quinnipiac University poll, Brownstein notes, shows her with only 27 percent of the white noncollege male vote—behind even Obama's 31 percent.

Of course, Hillary wouldn't need to win these voters; she would only have to stop the hemorrhaging of them to the Republicans. "She's not going to carry [white] noncollege voters. It's not like they have to get these voters to love them," says Ruy Teixeira, author of several books on how the white working-class votes. "You still need to do better than a catastrophic loss. There's a group in the middle that's willing to listen."

Conservatives are finding their way, too. So-called Reformicons are pushing more middle-class tax cuts and are emphasizing social issues in the context of helping working-class voters.

Reihan Salam of National Review and Ross Douthat of The New York Times have written, in their book Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream, that far from cultural issues being bait and switch, as Democrats charge, they are essential to working-class survival: "Public disorder, family disintegration, cultural fragmentation and civic and religious disaffection...breed downward mobility and financial strain—which in turn breeds further social dislocation, in a vicious cycle that threatens to transform a working class into an underclass."

Hard Hats Are Long Gone

Whichever approach is taken by the political parties to lure the white working class, it's going to have to go up against powerful forces that have reduced working-class wages around the globe. An economy that values more education and higher skills needs to make a special effort to assist those left behind.

The pollster Stanley Greenberg was a key architect of Bill Clinton's 1992 election. He studied white-majority Macomb County in Michigan, which had drifted from the Democratic fold. He found what's now a familiar pattern of alienation among working- and middle-class whites from the Democratic Party over everything from taxes to the death penalty.

He's more sanguine than many about the Democrats' prospects with white working-class voters and sees them, at least outside the South, Border States and parts of the Mountain West, as persuadable. "It's where race and religion meet," he says of those uncompetitive areas. But he thinks that when Democrats stop thinking of working-class whites as factory-floor hard hats—"They're long gone," he half jokes—and more likely cashiers and customer-service representatives, they'll be able to compete more effectively for their votes.

Andrew Levison, author of The White Working Class Today: Who They Are, How They Think, and How Progressives Can Regain Their Support, shares Greenberg's view about how many persuadable working-class voters remain. But he thinks a populist appeal isn't enough. He also notes that Democrats, let alone unions, are few and far between in many towns and a Fox News cocoon fills the void, while the Republican Party is a living presence. "It goes back to the loss of Democratic machines and institutions," he says.

It may be that, in time, demographics will settle the matter, as women and minorities vote in ever larger numbers, making the working-class white male less relevant to elections and to the economy. But no voice in American life should be ignored, even if it lacks the punch it once had.

Franklin Roosevelt lauded "the forgotten man." (Conservatives have used the phrase, too, and did so even before Roosevelt, who popularized it.) In an ideal world, each party would engage in a contest of ideas to help working-class voters. Election Day is close, but that day is a long way off.