Hugh Tovar, who was at the center of two of the CIA's most controversial covert action operations during the Cold War, died of natural causes just after midnight June 27. He was 92.

Tovar was the CIA station chief in Malaysia and Indonesia in the 1960s and then Laos and Thailand in the 1970s, while the U.S. and Soviet Union were locked in proxy wars around the world, most directly in Southeast Asia. For a time he was also chief of the CIA's covert action and counterintelligence sections at its headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

Tovar's assignments put him on the cutting edge of CIA operations at the time, much like the today's counterterrorism specialists, said Colin Thompson, a former CIA officer who served under Tovar in Thailand and later in the CIA's counterintelligence branch.

"Hugh was one of a small group of senior East Asia officers...who were to the CIA in the '60s and '70s what the [agency's] leaders in Middle East operations are today," said Thompson, who also worked in Laos, where Tovar was station chief from 1970 to 1973, at the height of the CIA's so-called "secret war" there.

The assignment to Vientiane, the capital of Laos, was a homecoming of sorts for Tovar, who had previously been sent there by the CIA's World War II predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, after his ROTC class at Harvard was called to duty by the U.S. Army in 1943. Born in Colombia as Bernardo Hugh Tovar—he rarely used his first name—he was raised in Chicago but attended Portsmouth Priory (now Portsmouth Abbey), a private school in Rhode Island run by Benedictine monks.

The CIA's later covert campaign in Laos was the biggest and longest paramilitary operation in the agency's history. It lasted from 1961 to 1975 and employed hundreds of CIA operatives and pilots and thousands of local Hmong tribesmen in a failed effort to block Communist North Vietnam from using Laos as a supply route and staging ground for attacks in South Vietnam.

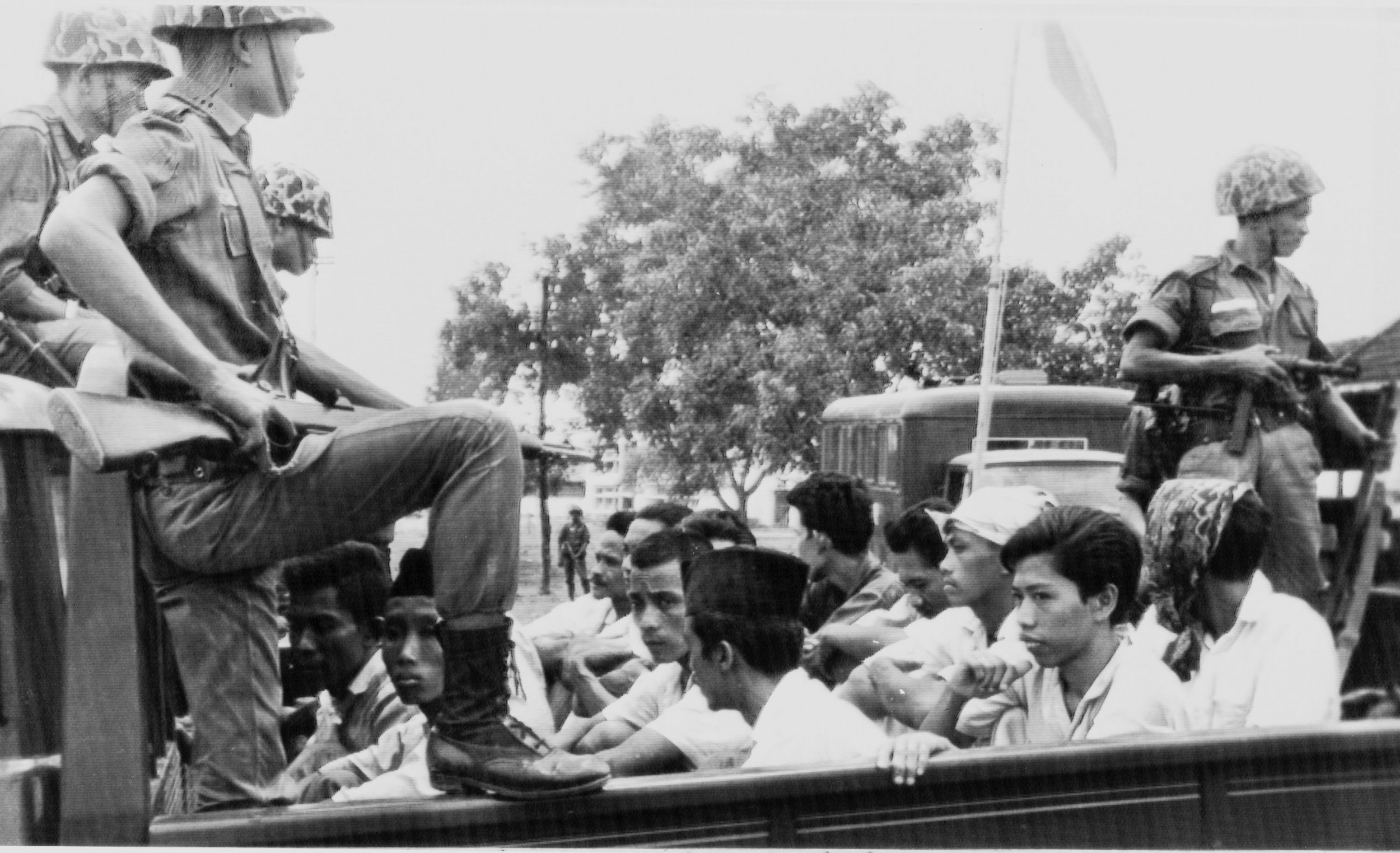

But it was Tovar's tenure in Indonesia in 1965 that has drawn the most scrutiny. At the time, the country's president, Sukarno, was leading a global "anti-imperialist" movement with the support of the Soviet Union and Communist China. Tovar, who had earlier worked against Communist guerrillas in the Philippines, was the CIA's Jakarta station chief. In September 1965, a coup attempt by the Indonesian Communist Party, or PKI, failed, and the military unleashed a genocidal campaign against the PKI's mostly ethnic Chinese followers. With the rebellion crushed and the military-backed Suharto regime now fully in power, the U.S. and other Western powers hailed the outcome as "the West's best news for years in Asia," as Time magazine put it.

"Hugh made his mark in Indonesia in the mid-'60s where he was COS [chief of station] during the very bloody anti-Chinese riots that led to the overthrow of Sukarno and the rise of Suharto," Thompson told Newsweek. "I understand he and the station performed very well."

Too well, according to a sensational 1990 account by States News Service journalist Kathy Kadane. She reported that the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta provided the Indonesian military with the names of suspected Communists, who were then hunted down and murdered.

"Over the next months, tens of thousands died—estimates range from the Suharto government report of 78,002 to an Amnesty International estimate of more than 1 million deaths," intelligence historian John Prados wrote in his 2003 biography of William Colby, a colleague of Tovar's who later became CIA director. An internal CIA report on the events in Indonesia, Prados wrote, called it "one of the worst episodes of mass murder of the 20th century."

Responding to Kadane's charges in The New York Times, Tovar denied he was involved in providing "any classified information" to an embassy political officer who in turn gave it to the Indonesians. In a 2001 interview with the Indonesian magazine Tempo, he also denied CIA complicity in the resulting carnage. "The U.S. did not in any way help the Army suppress the Communists," he said.

Tovar retired in 1978 but followed his second wife, Pamela Kay Balow, "on her assignments with the CIA to Rome, Singapore and Australia," according to the announcement of his death by the Galone-Caruso Funeral Home in Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania. He died "peacefully" at St. Anne Home, an assisted-living center in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, the announcement said.

In his retirement, Tovar became a measured critic of U.S. efforts to overthrow foreign governments. In a 1982 book of essays on covert action, he was quoted as saying the CIA's ill-fated 1961 invasion of Cuba was based on the mistaken notion that Fidel Castro's support was "so shallowly rooted...that he could be shaken by psychological pressures, as [President Jacobo] Arbenz had been in Guatemala [in 1954], and then ousted by a comparative handful of troops."

"Was it an intelligence failure?" Tovar said. "Undoubtedly, and in the grandest sense of the term."

Likewise, in Vietnam in 1963, a U.S.-backed coup backfired by weakening the Saigon government, Tovar wrote in another essay. "The overthrow of President [Ngo Dinh] Diem constituted the opening of the floodgates of American involvement in Indochina," he wrote. "By intruding as it did—crassly and blind to the consequences—the burden of responsibility for winning or losing was removed once and for all from South Vietnamese shoulders, and placed upon America's own."

Tovar also cautioned CIA leaders about discussing covert action options with their underlings, "whose instincts and training guarantee an immediate can-do response."

"Momentum develops rapidly," he said in the collection of essays, titled Intelligence Requirements for the 1980's: Covert Action. "Conceptualizing is superseded by planning. Policy emerges in high secrecy and, before anyone realizes it, the project is a living, pulsating, snorting entity with a dynamic all its own."

Newsweek national security correspondent Jeff Stein served as a military intelligence case officer in South Vietnam during 1968-69.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.