Humans are awash in microbes; they cover our skin, live in our nose and mouths, and, in any given person's body, outnumber human cells 10 to 1. But little is known about these microorganisms, how they are passed between people and their environment, and from where they hail.

To answer these questions, scientists followed around seven families from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, a group with 18 people, three dogs and a cat. They trained the families how to take swabs to capture snapshots of microbial populations from different places—their skin, floors, countertops, doorknobs—at various times, over the course of six weeks. Researchers then used advanced sequencing techniques to find out what bacteria lived where.

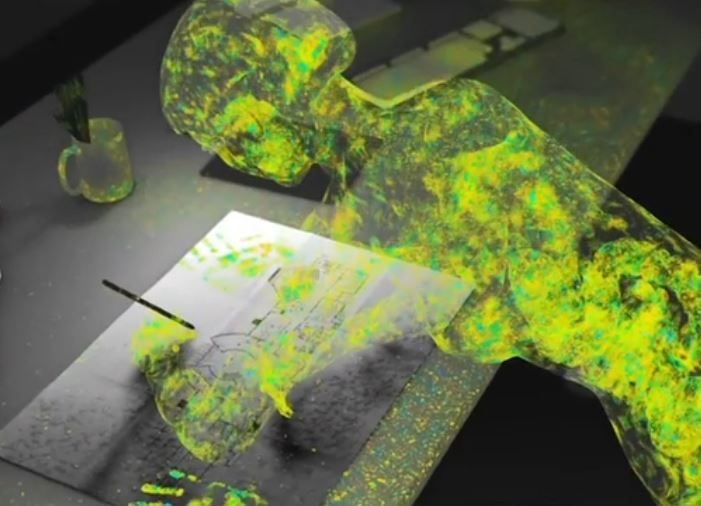

They discovered that each person and each family have unique "microbial fingerprints" or "signatures" that they bring with them everywhere they go—but they don't keep these signatures to themselves. Within about a day of moving into a new places, families "overwrite" the microbial signature of their new abode, says lead author Jack Gilbert in a video describing the study (below), who is a microbiologist at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Ill.

At the same time, this imprint is quite fleeting; if individuals leave their home for more than about a day or so, their microbial trace "decays or is replaced rapidly" in places "such as the bathroom, front doorknob, and kitchen counter," the authors wrote in the study, published today (August 28) in the journal Science.

In a house with one couple and an unrelated occupant, the couple, unsurprisingly, shared many more microbes. Married couples and their children also share most of the same bacteria, according to the study.

Bacteria appeared to mostly transfer in skin-to-skin contact, although the researchers also saw transmission via surfaces, especially the bathroom doorknob. The study found several potentially pathogenic bacteria on this surface and on the hands of two of the people studied, although it doesn't appear the people got sick.

Compared with elsewhere on the body, your hands are a virtual microbial Ellis Island, continually colonized by different types of bacteria picked up from other people and surfaces, only to be extinguished by new incomers or hand washing, according to the scientists. The microbes in your nose, however, are more steadfast and vary more from person to person, they found.

Understanding what microbes live on us and what they do is important because they affect our health and weight and even change how the brain develops, Gilbert said.

"The lion may live on the savanna," he said, "but we live in these built environments [like houses], which are now an essential ground from which to understand our health in the 21st century."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Douglas Main is a journalist who lives in New York City and whose writing has appeared in the New York ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.