My first library job was in the Kankakee, Illinois public library. Back then, I thought I was going to go to law school—I just needed a job.

Then, I saw how the library engaged the community with youth and adult classes. I saw a bunch of World War II veterans come together to share their story with the community. I became very interested in digitization—making information widely available, and in helping people find information.

I ended up going to library school instead of law school, and became a full-fledged librarian in 2010. Since then, I've been a branch manager, and I've been an administrator in the Chicago Public Library system, but I found out I don't like the politics. That's not me. I know who I am now.

Now, I'm an archivist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I do some research and writing, and work on digitization to make information accessible and help people find information. Opening access to information is my passion.

I was the manager of a small branch library in Indianapolis, and at the time, "street lit" books were really popular at that library. The language was as rough as the books' mean-streets settings. Since so many patrons were interested in reading books of that genre, my team and I moved street lit it to the front of the adult section.

One day, a patron complained. I liked her—she'd come in with her kids a lot. But she was a person who thought literature that's given shelf space in the library had to be more formal, and use certain grammatical structures. And yes, the library is for classic, formally written novels. But the library is for street lit, too.

Our executive director told us we had to move the street literature from the front to the back of the adult section. At first, I protested, and told my superiors that what they were doing was a form of censorship. Besides, just because one person doesn't like a book, it doesn't mean you should inconvenience all the other patrons that come in to our branch to get this material. But in the end, we had to move it.

This National Librarian Day, our country is dealing with misinformation and disinformation that threaten democracy and make crystal clear the need for the free flow of accurate information.

But instead of standing up for the robust exchange of ideas, lawmakers in state after state are pushing bills that would criminalize librarians for putting certain books on the shelves. Nuisance lawsuits and fights over book bans are draining librarians' time, energy, and resources.

Nobody becomes a librarian to become a pawn in the culture wars. But from book bans to bomb threats, we librarians are on the front lines of critical battles over who gets to control information.

The pursuit of happiness goes hand in hand with the pursuit of knowledge and information, which, in turn, is central to what libraries are all about. This goes to the heart of our jobs as librarians. We will keep up the fight, because it is access to information, not censorship, that fuels a healthy democracy.

I am proud to be a librarian—and rare. Less than 7 percent of librarians in the U.S. are Black. For Black librarians like me, libraries also symbolize the literacy that was denied to so many of our ancestors.

For our enslaved forebears, something as fundamental as learning to read was illegal and dangerous, but they did it anyway. After the Civil War, separate but "equal" schools that weren't equal and "colored" libraries whose books were filled with cast-offs from white libraries were key features of the Jim Crow era.

A whites-only public library in Alexandria, Virginia, saw one of the country's first Civil Rights sit-ins. In 1939, five Black men were arrested for asking to sign up for a library card and, upon being refused, sitting quietly and reading books until the police arrived.

Twenty years later, in Greenville, South Carolina, college students, including Jesse Jackson, held a sit-in at a white library that had a book they needed for an assignment but wasn't available at the library they were allowed to use. A year after that, Black students staged a library sit-in in Jackson, Mississippi. Three years later, Black students tried to enter a library in Greensburg, Louisiana, only to be locked out, day after day.

The methods are different, but today we are seeing the same impulse to distort access to information into a tool to suppress and control, and to make some people "other." Librarians are being fired for refusing to remove books about racism and the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community.

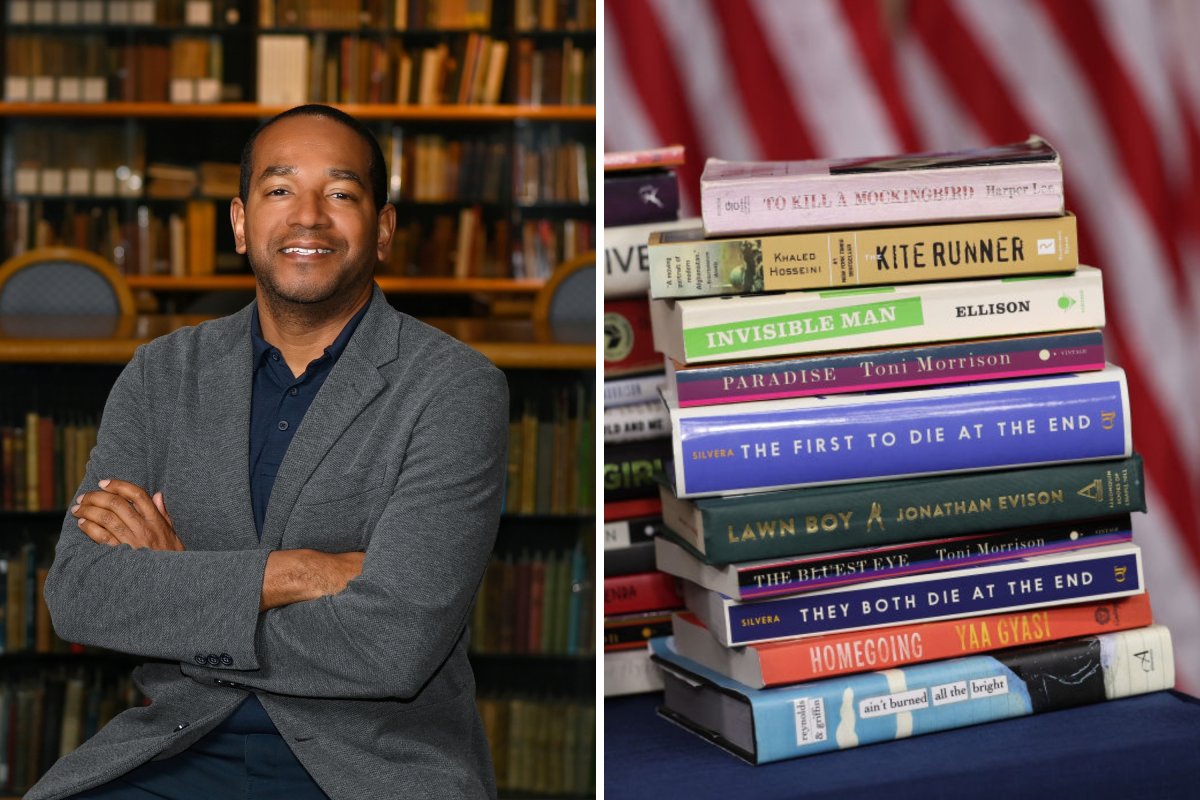

The American Library Association reports a record 4,240 book titles targeted for censorship in libraries and schools last year, from The Kite Runner by Afghan-American author Khaled Hosseini and the Pulitzer-prize-winning novel Beloved by Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison, to the Wizard of Oz retelling Wicked and Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, which was the inspiration for Hulu's critically acclaimed television series.

Black librarians pushed back against that evil during segregation and throughout the Civil Rights era, and continue to do so today. It's a history not even people in the profession know about, which is why I'm working on a documentary called Are You a Librarian? The Untold Story of Black Librarians.

I hope our documentary will inspire young Black people to consider becoming librarians, and I hope it will inspire all librarians struggling with today's hostile climate by showing them that librarians have a long record of defending the rights of every person to seek the information they want.

We librarians take pride in unearthing and sharing information. We work to engage young people in reading, offer internet access to those who need it, and guide people when a Google search is not enough to get to the heart of a matter.

My hope for this Librarian Day is that someday soon, we can stop worrying about politically motivated attacks on libraries – and instead, focus on the fundamental principle of free access to information, which should be at the heart of any healthy democracy.

Rodney Freeman Jr. is an archivist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte who has been a librarian since 2010. He is the producer of "Are You a Librarian: The Untold Story of Black Librarians."

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Rodney Freeman Jr. is an archivist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte who has been a librarian since ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.