The first time I stood up in court and answered questions about what happened on Christmas Day 1991, my voice was strong.

"Innocent," I said. I admitted that I was there at the bus stop by Popeyes on Canal Street but denied having a weapon on me. I stared the Orleans Parish DA in the eye and told him that I knew nothing about the killing of the fourteen-year-old boy.

I was lying.

I still remember everything about that night. Like how good it felt to be out with my friend, Leekie, after spending the whole day in the Eighth Ward with my family.

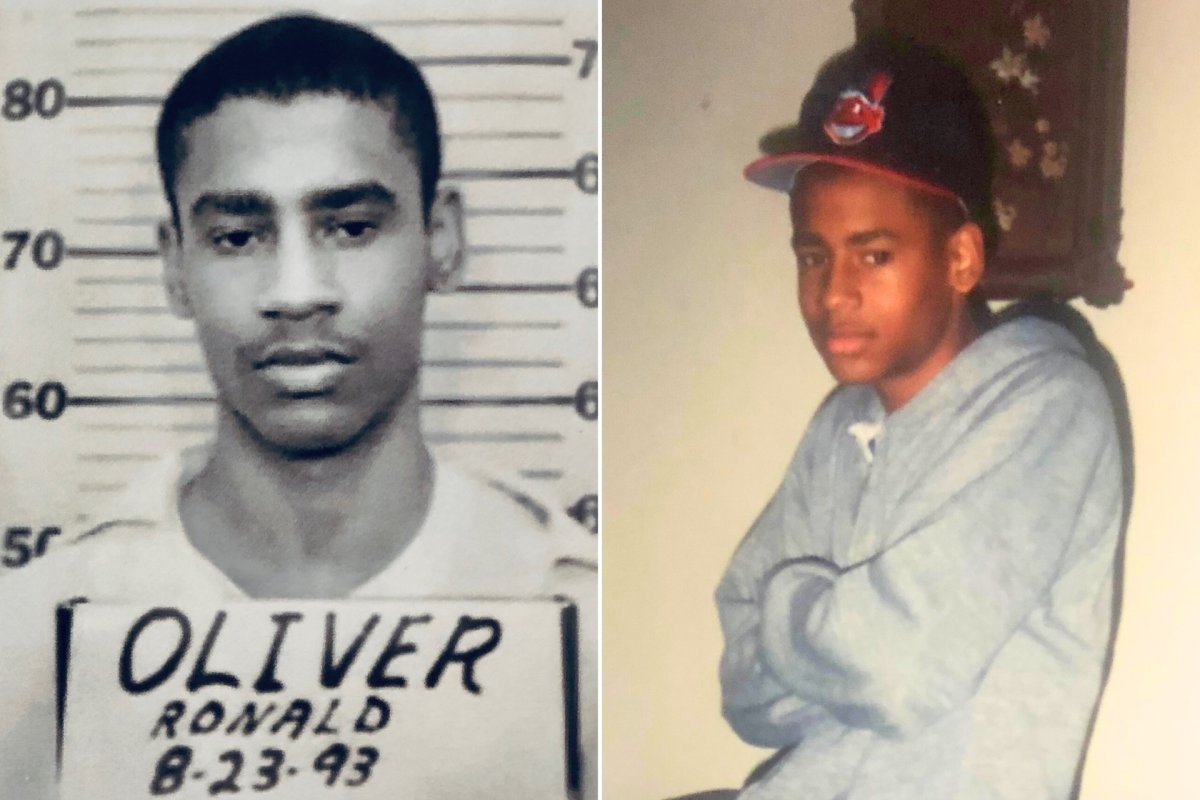

I was sixteen at the time, young enough for my Mama to still believe I was the hard-working, clean-living boy I pretended to be, but old enough to know that the real me was found out on the streets.

At home I was just Ronnie, but on the streets, I was Ronnie Slim. Out there—starter jacket on my back, my .38 special tucked in the waistband of my pants—I felt alive.

About 9 p.m. on Christmas Day, Leekie and I were out on Canal Street. I'd been talking with a girl for a few minutes when Leekie told me there was a group of guys staring at us. There were ten of them, and in the middle was a Duckie—someone we both had history with. Leekie said we should leave.

He was older than me, and even though I didn't like it, I knew he was right.

We walked.

They followed.

I reached for my gun, thinking that if they knew I had it, maybe they'd think twice about starting something, but Leekie stopped me. He hurried me over to the bus stop where we could blend in with the small crowd of people waiting.

A bus came within seconds. It wasn't going anywhere near the Eighth Ward, but as it pulled in, Leekie started moving toward the doors with the rest of the people.

"It's not ours," I said.

He glanced back over his shoulder. "We should get it anyway."

I turned back and saw Duckie and the others crossing the street toward us. Leekie was right, but I didn't want to push to the front the way he did. I would wait my turn at the back of the line. No way did I want Duckie to think I was running scared.

I had one foot on the bus step when I felt a hand on my right shoulder. It grabbed my jacket, spun me round, and hauled me back toward the sidewalk.

I almost tripped but was able to catch my balance. As I turned, I saw all ten of the guys standing there. Duckie hadn't grabbed me, but some kid I didn't recognize. Duckie stood right by him, eyes blazing. The other eight were standing back. If they were a threat, I'd deal with them next.

I pulled my gun. Shot the kid who had grabbed me first. Then I turned to Duckie and fired several times at him. I turned back to the kid and fired my remaining bullet.

I looked at the other eight who had been with them. They were motionless.

I leapt back onto the bus and looked for Leekie. He was sitting at the back, shouting at the driver to get going.

Someone else was shouting too. An old man, sitting up by the front. "They tried to rob you, boy. I saw it all!"

As we drove away, I told myself the same thing, that I was innocent, that I'd acted in self-defense. But I knew the truth. I knew that I was the aggressor, that it was on me.

What I didn't know was what damage I'd left behind. I doubted I'd killed either Duckie or the other guy. In my neighborhood I'd seen plenty of people shot and live to display their wounds with pride. And every other time I'd fired my little .38 I'd either not had any bullets in it or I'd missed my target completely.

But I was scared—scared that Duckie would come by my house and take his revenge out on my family.

The next day I was watching the local TV news when it cut to a reporter standing on Canal Street, across the road from where the bus had stopped. Behind him was police tape, and he was describing exactly what had happened.

Only, it wasn't the same version I'd been telling myself. The reporter wasn't talking about an attempted robbery, he was talking about a murder. Of the two people who had been shot, one—Duckie—was in critical condition and the other was dead.

I was surprised, but a part of me was a little skeptical too. TV news treated what went down on the streets like it was bad entertainment, and I wasn't at all sure they were telling the truth about who was alive and who was dead. But I was curious.

I was also confident. Every other time I'd been in trouble with the police I'd been sent away with nothing worse than some strong words. I was still sixteen, a minor in the eyes of the law.

So I went to the police. Told them my story about the attempted robbery and assumed I'd be home that same day.

It didn't work out that way.

Months later I was in court, lying to everyone about what had happened. I was on trial for first degree murder, with twelve people deciding my fate. If they found me guilty, I'd get the death penalty.

While the jury deliberated, I sat alone in a holding cell. I was terrified, but somehow remembered something my Mama had said to me years before.

"You know, baby, if you ever have real trouble, the kind I can't get you out of, you can always call on Jesus."

The memory was brief, but the weight of Mama's words was immense.

I rolled onto my knees. Tears were instantly all over my face, pooling on the concrete floor. It was difficult to fight through the sobs and force the air into my lungs.

But I was praying. Somewhere, from the deepest part of me, the words were screaming out: "Lord, if you don't let them kill me, I will serve you the rest of my life."

Soon, I felt peace. I didn't know whether I was going to be released or sent to jail for a time, but I knew I was going to be okay. I knew it the way you know that when you're deep underwater, all you need to do is break the surface to be able to breathe again.

An hour later I was back in the courtroom listening to the jury's verdict. I was not found guilty of first-degree murder, but they did find me guilty of second-degree murder. I had escaped the death penalty but was sentenced to life without probation or parole. I would spend every moment of my remaining life behind bars.

It seemed to me that there was not much difference between the life sentence I'd been given and the death sentence I'd escaped, but I didn't spend long thinking about it. My sentence was to be served in Louisiana State Penitentiary—known to the world as Angola, one of the country's most notorious prisons. For a kid like me, survival was going to be a daily battle.

For the first years of my sentence that's all I did: Survive.

Slowly, things changed. I met good people who took care of me—many of them chaplains and pastors and other inmates whose own lives had been turned around for the better.

They encouraged me to join a public speaking class, get my GED, go to Bible college, and to learn all I could from the law library. Mostly, they showed me what it means to live right: to forgive, to love, to serve, to be a follower of Jesus.

And so, that prayer I'd sobbed on the floor of the holding cell came back to me. My own life changed. I let go of the person that I'd had to be to survive out there on the streets. I became the man I believe I was created to be. Ronald Olivier, not Ronnie Slim.

For all the courses that I completed and the programs that I helped deliver, there was one part of my transformation and healing that could not be completed in prison. One part that I had to wait patiently for as the years passed by.

I wanted to talk to the mother of the boy I'd killed and tell her I was sorry.

It took more than twenty-five years in prison before I had that opportunity. The chance came when a Supreme Court ruling deemed that giving a minor a life sentence was unconstitutional. I was given the opportunity to appear before a state judge and appeal to become eligible for parole.

As soon as she walked into the courtroom, I recognized the boy's mother. My lawyer asked the DA if I could speak with her, and eventually she came over and sat in the row behind me. Her arms were folded. Here eyes like steel.

I took a deep breath. The only time she'd heard me speak was at the trial, twenty-five years earlier—the day when I'd lied and denied everything.

Now I wanted to do what I could to put that right.

"Ma'am . . ." I could feel my voice trembling inside me. I felt light-headed, as if the air was thin. "Ma'am, I take full responsibility for the death of your son."

Everything else faded to the background. The noise of the courtroom, the bite of the metal in my wrists and ankles, even the DA sitting next to her. None of it held any interest to me. None of it mattered. The only thing I could focus on was her. The mother whose grief I caused. The mother whose son I killed.

I tried to carry on talking, but I started crying instead. I tried to stop, to let myself speak, but nothing would stop the tears. Through the blur, I could see her sobbing too.

"It was stupid," I said when I eventually caught my breath. "It was idiotic. I was very impulsive. I wasn't thinking. I just reacted. It shouldn't have happened. Ma'am, I just ask that you forgive me. I pray that somehow you could find somewhere in your heart to forgive me."

She looked at me. "I don't hate you. But what you did completely changed my life. You know, my son being killed? But I forgive you."

A lot has changed since that day. I am a free man. My wife and I have a son. I worked as the director of chaplains at a state prison. Now I have a job helping formerly incarcerated people create new lives. I have a mortgage. A cell phone. A dog. And I know that I am forgiven.

I. Am. Forgiven.

I am a free man.

Ronald Olivier is the author of 27 Summers: My Journey to Freedom, Forgiveness and Redemption During My Time in Angola Prison. He served twenty-seven summers in the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola. He was released in 2018 and became a client of the Louisiana Parole Project. In 2020, less than two years after leaving Angola, Ronald was hired as the director of chaplaincy at the Mississippi State Penitentiary. In 2023 Ronald returned to the Louisiana Parole Project as a client advocate, using his experience to guide other formerly incarcerated people toward successful careers and lives. He lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, with his wife and son.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ronald Olivier is the author of 27 Summers: My Journey to Freedom, Forgiveness and Redemption During My Time ... Read more