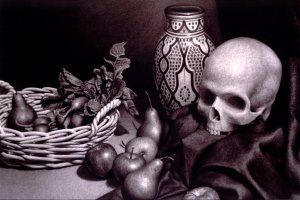

When we consider the problem of aging, and imagine that we might be able to cure it, that alternating current we feel consists of longings and dread. We are afraid of what we wish for; and most of our fears, like our hopes, have always cycled in us. Dreams of immortality have led to terrible nightmares of boredom ever since people began writing down their thoughts.

"Who the hell wants to live forever? Most of us, apparently; but it's idiotic," Truman Capote writes in his essay "Self-Portrait." "After all, there is such a thing as life-saturation: the point when everything is pure effort and total repetition."

We already overcrowd much of the planet. We bestride and consume it, present and future. We eat so much more than our share that the generations following us will inherit a very poor place to live.

And yet real advances in science have raised the question of just how long we might live. "Very long lives are not the distant privilege of remote future generations," according to an analysis by the Danish gerontologist Kaare Christensen and colleagues. "Very long lives are the probable destiny of most people alive now in developed countries." Life expectancy has been rising on a straight line for more than 165 years. This linear progress "does not suggest a looming limit to human life span," they argue. "If life expectancy were approaching a limit, some deceleration of progress would probably occur. Continued progress in the longest-living populations suggests that we are not close to a limit, and further rise in life expectancy seems likely."

If a cure for aging became available to the rich before the poor, which is the way the world always turns, then the unfairness of life might become absolutely unsustainable. How would our world of haves and have-nots go on spinning if the haves lived for a thousand years while the children of have-nots went right on dying hungry at the age of 5? And what would happen to the rest of the living world? Would the other species on the planet, the other earthlings, have even less?

We want a good long life. We also want a good life. It's hard to see how members of our species could have both for very long if more and more of us had to make do with less and less. Still, the adventure of living another 500 years on a planet as overburdened as ours would be, if nothing else, an antidote to boredom. Maybe, just maybe, we would tread more lightly on the Earth because we would each preserve one body, one piece of human equipment, instead of continually having to replace it. In that sense, thousand-year lives would be the ultimate in conservation. We might even grow up faster as a species if we lived long enough to pay the price for our species's sins in our own skins.

In our lifetimes, we may figure out how to add years to our lives by slowing aging. Human growth hormone has been taken for that purpose ever since 1990. There's no solid evidence that it works. Even so, it is sold by antiaging companies, hawked everywhere on the Web, and recommended by the controversial American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine, although biogerontologists denounce the academy and its claims.

What happens when we have real antiaging pills that pass the tests of clinical trials? As bioethicists have begun to note, this is a problem that would make all our bioethical debates to date look small. What are the bioethical problems that have exercised us in the last 10 or 20 years? Stem cells. Cloning. Gene therapy. The privacy of genetic information. Steroids. All these problems matter in themselves, but all of them would be subsumed in the transformations of society and human nature that would be wreaked by a significant success with the human life span. And then will come the option of changing the genome itself. We will add or subtract genes to lengthen our lives, until there is no going back, because no human beings alive (however long they may live) will ever be human in the same way again. If we are going to survive to enjoy a good portion of the future, our health and happiness depend on a great deal of luck. The trouble with immortality is endless.

From Long for This World: The Strange Science of Immortality By Jonathan Weiner, Published By Ecco, An Imprint Of HarperCollins Publishers ©2010 By Jonathan Weiner.

Healthy Living: The Complete Package

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.