The coronavirus pandemic and 2020 election are drawing even more attention to the dangers of misinformation on social media. This month, Facebook announced the members of its new independent oversight board designed to tackle "hateful, harmful and deceitful" content on its platforms. Less than a week later, Twitter announced its new labeling system for "disputed or misleading information related to COVID-19."

These are welcome developments, but as an expert in lie detection, I've learned that even vigilant examiners can't prevent the most pernicious kinds of misinformation. Here in the "infodemic," we have to be our own content moderators.

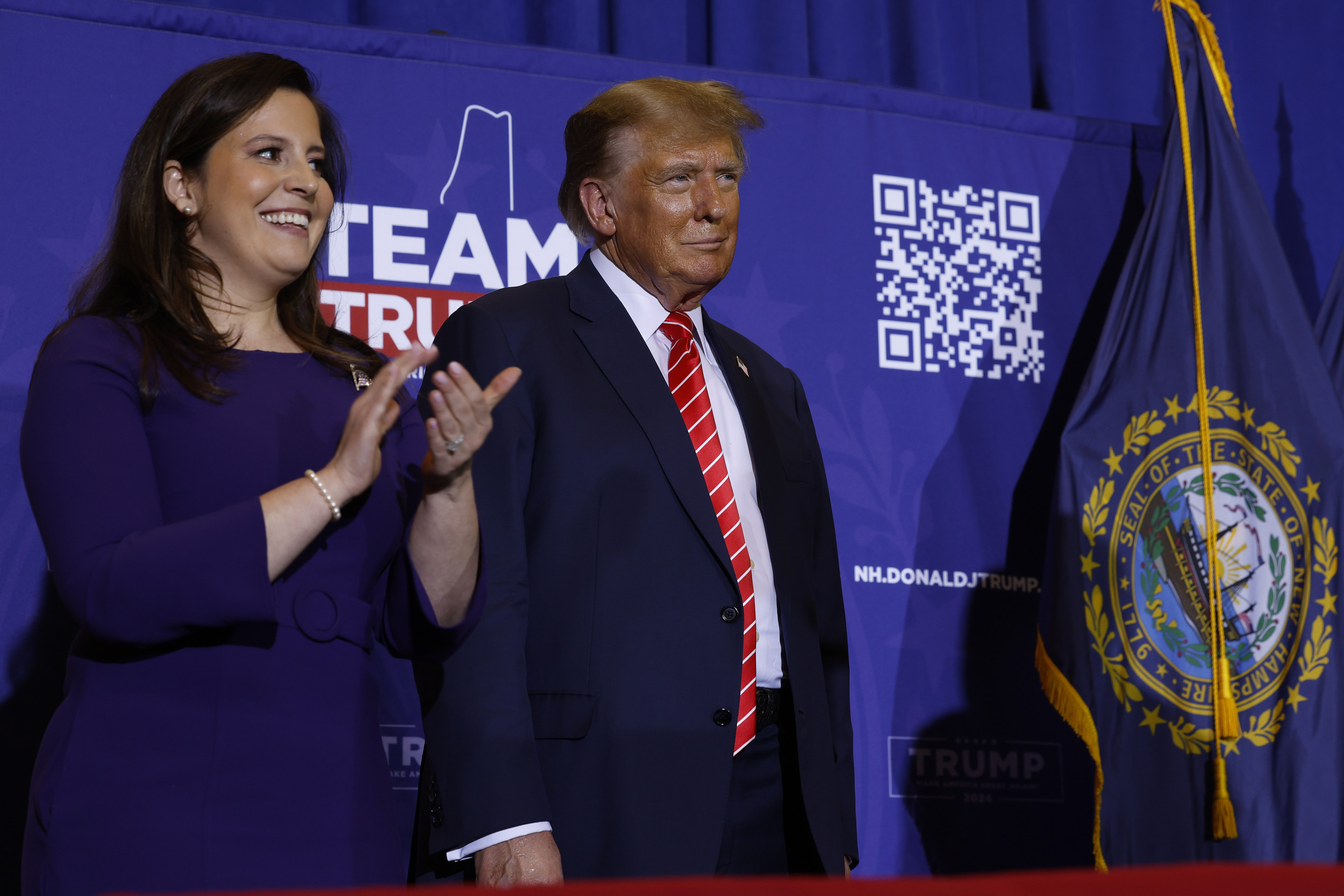

That means more than calling out the charlatans swooping in to fill the void left by lumbering authorities. From fringe conspiracy theorists to President Donald Trump himself, some liars are just obvious. If we want to take informed citizenship into our own hands, then we need to be on guard against the kinds of misinformation that lurk between the lines.

Consider three subtler—and far more contagious—forms of deception.

Cropping Context

Anyone who's taken a selfie knows about the crop feature, but erasing the big picture is something we do all the time, whether we know it or not. Cropping information is akin to lying by omission, except instead of the truth, you're omitting the relevant context. Without an accurate frame of reference, it's hard not to distort facts, exaggerate findings and hold up isolated incidents as proof of some larger trend.

Take the recent media obsession with a handful of anti-lockdown protests. It's reassuring to know that nearly 60 percent of American voters would rather prevent the spread of COVID-19 than rush reopening the economy. But that context was largely missing from the coverage. Even more troubling, the parade of America's most ridiculous protesters extended a veneer of silliness to far-right extremists, who are exploiting the circumstances to attack Asian-American, Jewish and immigrant communities.

Bothsidesism

We're all prone to thinking in binaries. Not only do we reduce complexity into black-and-white or good versus bad, but we also pretend there are two sides to every story—even if one side is unbelievable.

In America, intense polarization makes it easy to mistake false equivalence for balance. For instance, when The New York Times first reported Trump's ludicrous theory that coronavirus might be cured by ultraviolet light and ingesting household cleaners, the paper noted that it was dangerous "in the view of some experts." Which is like saying the Earth is round in the view of some astronomers.

Similarly, after world leaders touted malaria drugs as viable treatments for COVID-19—a recommendation unsupported by medical consensus—cable news shows staged split-screen debates between experts weighing the pros and cons of these drugs. But at this point, intelligent debate is moot. Just the setup implies that it's an open question whether hydroxychloroquine is a medically approved treatment for COVID-19. In fact, it is not.

Whitecoating

Isn't it strange how many people have been blessed with expert insight into a crisis that's eluded so many of the world's leading experts? In the wake of vague and conflicting recommendations from leading health officials, it's as if every pundit, politician and internet user threw on a white coat just to share some free advice about epidemiology, or virology, or pharmacy. While they're at it, they're playing economist too. Why not?

Unfortunately, passing along advice that's better left for the experts is a universal human frailty. Solid credentials are no guarantee of immunity: Even a Harvard epidemiologist has been slammed for swerving out of his lane. What makes whitecoating so pervasive is that many of the worst offenders don't even think they're doing it. For instance, when I look at the "holistic psychiatrist" endorsed by Gwyneth Paltrow, or the handful of celebrity 5G-skeptics, I don't see garden-variety deception. These are true believers.

When I train investigators, the best advice I give is to pursue facts, not people. At a time when public health depends on public information, we can't rely on anyone to do that work for us. We have to examine the information we're presented with, clearly and carefully. We have to constantly ask ourselves, Could they be wrong? Could I be wrong?

Lie detection can be exhausting, but believe me, the truth is worth it.

Pamela Meyer is CEO of the deception detection training company Calibrate, and the author of Liespotting. Her TED talk has been viewed over 28 million times.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.