The Iranian wrestler stands in his glorious embroidered breeches, stripped to the waist, holding some paraphernalia of his craft above his head. The walls are festooned with portraits of successful wrestlers and Shiite saints, the angle of the photo cropping the image so that the wrestling school feels like a religious shrine—which, in some sense, it is. It is also, the caption tells us, an absolute male preserve. So who's that reflected in the mirror, down on the floor, with a camera clamped to her eye, but the photographer Mehraneh Atashi herself?

This sort of playful touch was not, I admit, what I expected from an exhibition of photographs from the Middle East. War, revolution, migration, the role of women, history ancient and modern—there's plenty for any artist to get his or her teeth into, including the uses of representation and religious attitudes to portraiture. But Light From the Middle East is not exactly about the Middle East, which the show consciously defines in the broadest terms. Running for four months at London's Victoria and Albert Museum, it's an exhibition of photographs involving light and its manipulation.

The curator, Marta Weiss, has broken the images down into three sections. Recording kicks off with photojournalist Abbas's record of two years of Iran's Islamic Revolution: stark, essayistic images of mullahs marching, veiled women getting gun training, the bodies of four generals in a morgue. But already one image is turning into a vehicle for another—in Abbas's pictures, we see a portrait of the shah being burned in the street, veiled women perusing rows of tiny photos of victims of the secret police, revolutionaries posing with properly clenched fists.

As the show develops the instances of "recording," it becomes more subjective and uncertain. Mitra Tabrizian's big color print Tehran, 2006 is a long way on from the revolutionary dramatics of 1979. In a scrubland beside a block of flats, under a looming billboard with a portrait of two mullahs, a number of ordinary people are standing, walking, waiting. Some hold shopping bags. Who acknowledges whom?

Photographer Manal Al-Dowayan does portraits of Saudi working women, as in I Am an Educator, encumbered by heavy traditional jewelry; I Am a Saudi Citizen shows a woman in profile—her bangled wrist, inscribed headscarf, and filigree mantilla leaving no part of her uncovered, except the bare white hand that holds the scarf.

And Jananne Al-Ani has created a haunting montage of aerial shots of a desert taken at dawn or dusk, when the shadows are deepest. One slide fades into another as a soundtrack plays, revealing the wastes to be not only inhabited but also historically alive, even if that history is illegible and conjectural: compounds, crumbling walls, enigmatic scratches on the sand, marks and scars of uncertain scale.

Reframing, the second section, groups together works that enlarge, subvert, or alter the image in context. I loved Raeda Saadeh's Who Will Make Me Real?, in which she gazes out at the viewer, reclining like an odalisque from Ingres, but dressed instead of nude—in a suit made of Palestinian newspapers! Or the cheerful yashmaked ladies of Hassan Hajjaj's Jama Fna Angels coming down an alley in a fancy mix of Western couture and Marrakech funkiness.

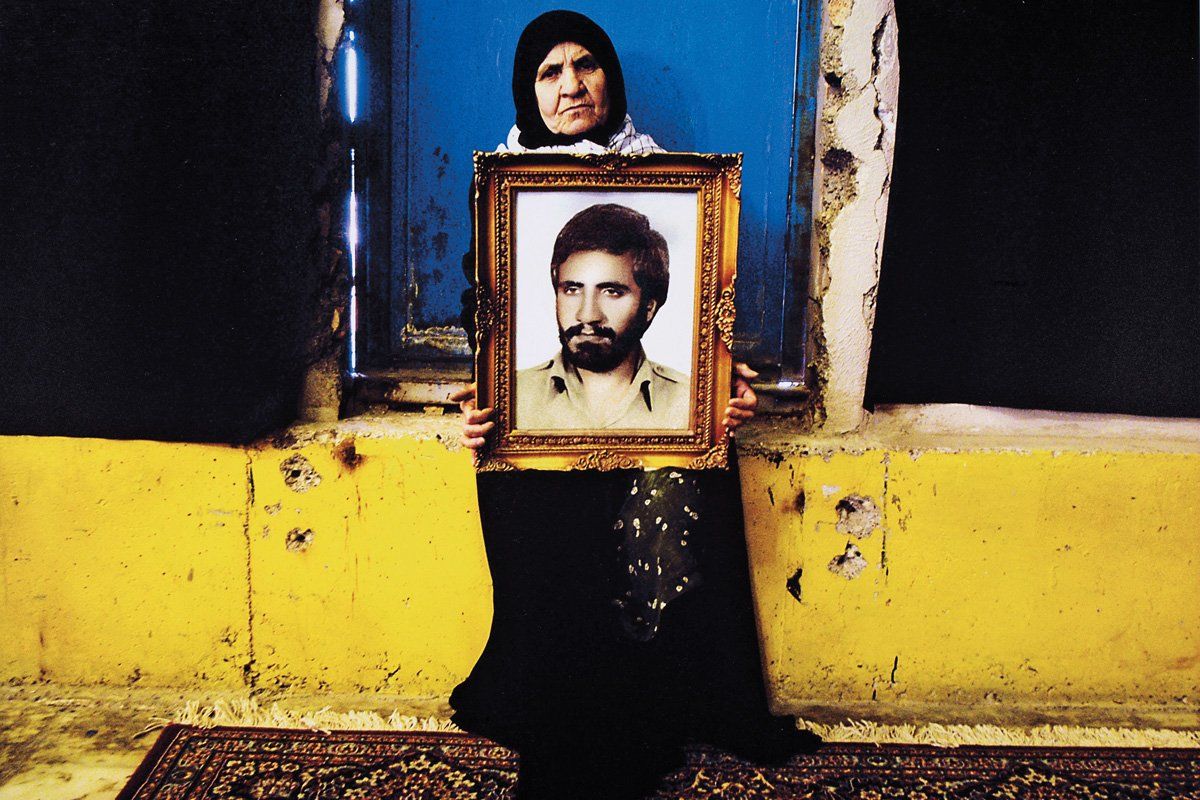

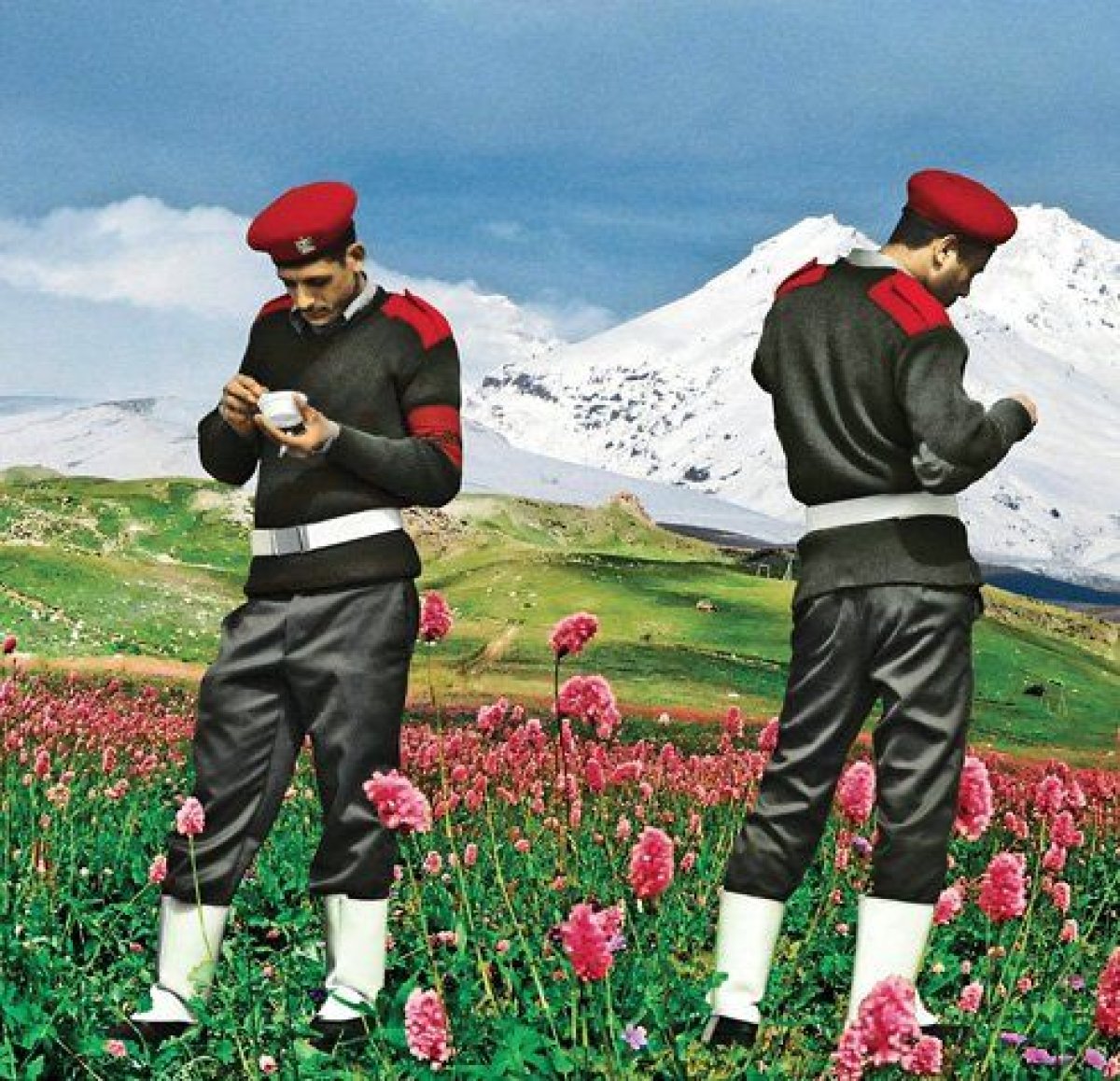

In Resisting, the third section, the image breaks up or melts down, partly in response to violence, repression, or civil war, but also partly, as the curator notes, because the medium itself is unstable. It is said that the camera always tells the truth, but photos can lie. Taraneh Hemami takes mug shots from a wanted list and blurs and scratches them so that the original portraits have become generic "Muslim" faces, recognizable as an assemblage of headscarves, mustaches, hair color. Amirali Ghasemi's Party shows young Iranians at a farewell fete, their flesh blanked out so we cannot tell who they are or what their expressions might be. Nermine Hammam brings the show bang up to date with shots of soldiers taken in Tahrir Square superimposed against pretty landscapes.

It's a great show to be enjoyed on many levels, but what strikes me most about the various artists is their wit. It may be black humor—the sort that notes, in precise and enlarged detail, the face of pretty Bryan Adams on a T-shirt worn by an Iraqi warrior or makes a 19th-century daguerreotype of a veiled woman in shades—but it leaves one with a strong sense of cultural richness. And it convinces me that the issues that face all of us, in the Middle East as elsewhere, are far too serious to be left to people who don't have a sense of humor.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.