Capital & Main is an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political and social issues.

In late August of last year, Moises Tino Lopez, 23, drove his wife, Petrona Juarez Tino, to an appointment with immigration authorities near their Grand Island home in Central Nebraska. Officers questioned Juarez Tino about her husband as he and the couple's 2-year-old daughter waited in a nearby parking lot. Before Juarez Tino's appointment was over, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers arrested her husband on a previous deportation order. They delivered the toddler to her mother and booked Tino Lopez into the local jail, which also houses ICE detainees.

Less than a month later, Tino Lopez lay in a hospital bed, brain-dead and completely dependent on a ventilator to breathe.

On September 27, Tino Lopez's family gave doctors permission to disconnect him from life support; the official cause of death was a brain injury brought on by seizure-related cardiac arrest, during which the brain was starved of oxygen.

"We don't know what happened to him in jail," said Juarez Tino. "He wasn't sick, he was working in construction." She noted that he had headaches, for which he took over-the-counter medication, but no history of seizures.

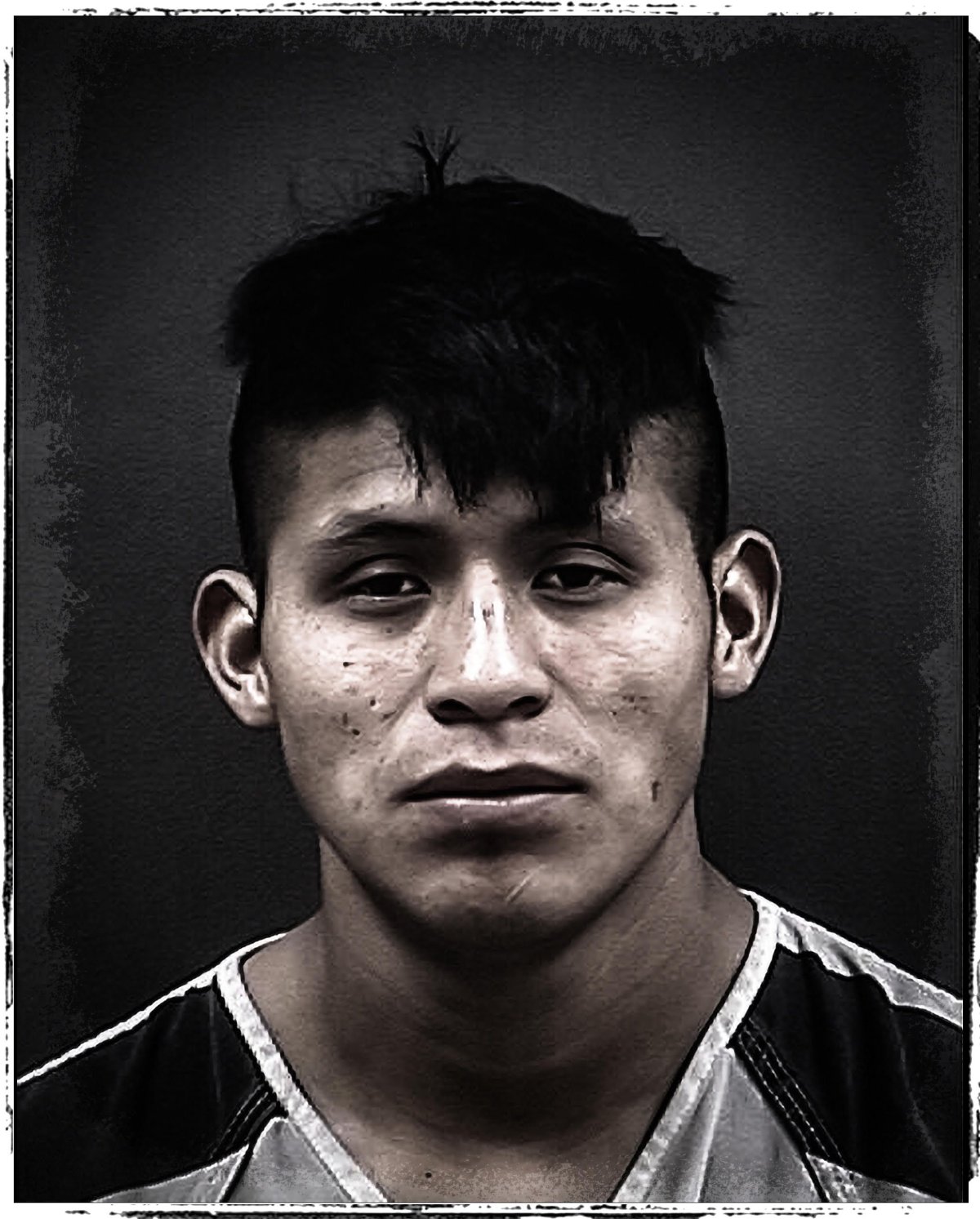

In a Hall County Department of Corrections mug shot, Tino Lopez, who was short and slight, looks straight at the camera with a serious expression. His head is shaved on both sides in a fade and a shock of black hair falls over his forehead. "He was friendly. He was never rude," Juarez Tino recalled. She said the two had settled in Grand Island with Tino Lopez's sister just two months before her husband's arrest. Grand Island's large meat-packing plant and generally healthy job market has drawn scores of new immigrants—mostly from Latin America and Somalia.

The couple had grown up as neighbors in the small town of Joyabaj in Guatemala's highlands, and married four years before Tino Lopez's death. Juarez Tino speaks Spanish with the accent of her native K'iche, the Mayan language of her region. Her husband was a saxophone player who loved making music and singing. "But what he loved most," Juarez Tino said, "was his daughter." She's 3 and a half now, and will start preschool in January.

It's an open question whether Tino Lopez would be alive if he hadn't landed in the Hall County Jail. But it was clearly bad luck that got him locked up in the first place.

According to Rose Godinez, an American Civil Liberties Union attorney, Tino Lopez would have had a chance to fight his case with a competent immigration attorney. He hadn't committed a crime in the United States; he was ordered deported simply because he had entered here illegally, was caught and later failed to check in with immigration authorities, possibly because he didn't understand the requirement.

He probably had a case for asylum, according to Godinez. Tino Lopez and his wife claimed they had been threatened by gun-wielding supporters of a mayoral candidate they had opposed in Guatemala, and said they feared for their lives. Juarez has since been granted a work permit in her asylum case on the same grounds, and has been told by her attorney that she'll likely prevail.

Substandard Care?

Tino Lopez's death triggered a criminal investigation by the Nebraska State Patrol and a grand jury proceeding, both required by Nebraska law following inmate deaths. The grand jury determined no crime was committed in his death. But an ICE review concluded that the Hall County Jail, which currently houses some 80 immigrant detainees, violated a number of ICE federal detention standards on medical care, and took other questionable actions that concern the agency.

All told, the documents raise questions about the jail's ability to properly care for medically vulnerable detainees.

In recent years ICE has come under fire for alleged substandard medical care in detention centers and in county jails. In a Human Rights Watch report released earlier this year, two physicians who reviewed 18 ICE detainee deaths found that poor care probably contributed to seven of them.

At the Hall County Jail, as in many ICE detention facilities, health care is provided by a for-profit contractor. Advanced Correctional Healthcare, based in Peoria, Illinois, serves more than 250 jails and prisons in 17 Midwestern and Southern states and, on its website, states the company is saving thousands of dollars for local governments. But in the past 12 years, more than 150 inmates or their families have filed suit against the company and the local jails it serves, alleging they were hurt or their loved one killed as a result of poor care from ACH. Three wrongful death suits have been lodged in federal court against the company in the past six months alone.

ACH nurses began caring for Tino Lopez when he suffered a sudden seizure after about two weeks in jail. A nurse practitioner prescribed Tylenol and an anti-seizure drug, and noted that Tino Lopez should see a neurologist. Eight days later, he was taken to a lab for a CT scan, which revealed a possible abnormality but not the cause of his seizure.

The lab recommended a follow-up MRI to check for possible brain lesions, but ICE found the jail took no action to order the test, and never arranged for him to consult with a specialist.

After his seizure, jail documents show, Tino Lopez's headaches continued. He complained of vision issues and told his wife that the anti-seizure medication was making him sicker. He was placed in solitary confinement after arguing with a fellow inmate and reported to a guard that the inmate had pushed him. Such disputes don't warrant disciplinary segregation, according to the jail's handbook. On September 16, Tino Lopez began refusing his medication altogether, even though nurses had switched to a different drug the day before. He was warned that refusing his meds could result in another seizure or even death. It's unclear whether Tino Lopez, who spoke only Spanish and K'iche, understood the warnings or could adequately and openly explain his symptoms to jail nurses.

The grand jury testimony revealed that jail nurses simply continued to offer Tino Lopez the second medication to no avail, and the ICE review noted that they failed to notify their supervising nurse practitioner of his refusals. Three days after he stopped taking his meds, an officer found Tino Lopez unconscious and seizing in his cell. This second time, he was weaker and slower to come to. He had vomited after his seizure and again as officers attempted to walk him to a first-floor cell. He was so unsteady that officers carried him down the stairs to his new bunk.

In the minutes that followed this second seizure, jail nurse Angela Barcenas, a licensed practical nurse, considered sending him to a hospital. She consulted with Tammy Bader, the nurse practitioner who oversaw health care at the jail from her Omaha office and in weekly visits. Bader approved the hospital visit. But after Barcenas reviewed Tino Lopez's medication refusals, she consulted Bader again. "She's like, 'That's probably why he's having seizures. We need to monitor him,'" Barcenas told the grand jury.

"The first [seizure] should have prompted a high level of concern and attention," commented Dr. Marc Stern, a correctional health-care expert who formerly served as health services director for Washington state's Department of Corrections. "And if the first one didn't, the second one should have." Stern, who consulted on Human Rights Watch's ICE report, noted that seizure can be a sign of something more serious—even potentially fatal—caused by trauma, aneurysm or infection.

But Barcenas opted not to send Tino Lopez to the hospital. It's unclear why she decided to keep him in his cell, but shortly afterward met with him a final time and, with a fellow inmate interpreting, Tino Lopez agreed to take his medicine later that evening.

Series of Missteps

About four hours after Tino Lopez's second seizure, however, corrections officer Steven Greenland found him lying face down on his mat. Believing he was asleep, Greenland went to check on other inmates, but realized something was amiss and knocked on the detainee's window moments later. There was no reply. Nor did Tino Lopez respond when Greenland entered the cell and shook him. "I tried rolling him over on his side and that's when I noticed his face was blue and then all the vomit... came out of his mouth," Greenland told the grand jury. Tino Lopez had no pulse and wasn't breathing. Greenland radioed for help, and he and other officers began CPR, brought oxygen and the jail's defibrillator.

No one knows exactly when Tino Lopez's final seizure began—another officer had checked his cell 15 minutes before Greenland found him unconscious. But, had he not been in solitary in violation of jail policy, fellow inmates could have called for help at the moment he began seizing, said former Hall County Jail sergeant Debb Rea, who retired in 2015 after 30 years. Rea sued the Hall County Department of Corrections in 2016, alleging she'd been pushed out, in part, because she'd complained about unwarranted use of solitary confinement.

The ICE report found no justification for placing Tino Lopez in solitary.

A six-minute delay also occurred in calling 911. Jail policy is to call 911 immediately, according to Hall County Department of Corrections director Todd Bahensky. "We act as quickly as we can," he said. "I know the officers here and I watched them giving CPR and I know these people were doing everything they could to save his life. Unfortunately that wasn't to be."

This story touches on some of the same issues that have appeared in other detention-death cases, especially regarding translation protocols for non-English speakers, delays in providing needed care and inadequate medical staffing.

ICE's review noted that its findings "should not be construed in any way as indicating the deficiency contributed to the death of the detainee."

But ICE reviewers document a series of missteps that call into question whether Tino Lopez's life could have been saved if he'd received proper care.

ICE's review found the detention center's nearly exclusive use of LPNs supervised by a nurse practitioner who is available by phone, but present just one to three hours per week, falls short of the requirement that its medical staff be "large enough to perform basic exams and treatments for all detainees."

The reviewers noted that Tino Lopez was warned of the consequences of refusing his medicine, but because of the language barrier, they wrote, "it remains unclear if Tino understood the potential consequences of non-compliance." ICE inspectors, who interviewed jail and hospital staff, found that Tino Lopez, whose first language was K'iche, spoke no English and limited Spanish.

But the Hall County Jail didn't even use qualified Spanish interpreters. Instead, they relied upon guards, a fellow inmate and even Google Translate to communicate with Tino Lopez.

"It's grossly inadequate," said Dr. Marc Stern, who reviewed parts of the grand jury transcript and exhibits. "It's totally in violation of ICE detention standards, HIPAA [the medical privacy law] and it's just wrong."

Todd Bahensky said that officers or medical staff felt they could get information from Tino Lopez without using professional interpreters.

Interpreting snafus can cause big misunderstandings, said Cynthia Peinado, who offers classes for fellow medical interpreters in Nashville, Tennessee. She recalled that a surgeon with whom she had worked expressed pride in her use of Google Translate—until she learned that the app had instructed her patient to pour salad dressing on a wound, instead of re-applying a bandage.

The ICE report further found that medical staff failed to properly monitor Tino Lopez after deciding not to send him to the hospital and did not properly document many of its actions. It didn't give Tino Lopez an adequate medical exam or ask him questions about any history of seizure, and it doesn't have a written seizure protocol.

Tino Lopez's death also poses questions about the care that detainees receive across the country, said Victoria Lopez, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU National Prison Project.

"We should be paying attention to each of these deaths because they bring up problems and deficiencies in this sprawling system," noted Lopez, who reviewed some of the documents in Tino Lopez's case. "It raises questions about continuing to fund this detention system and the need to continue detaining so many people."

An ICE spokesman declined to comment for this article in time for publication. Officials at Advanced Correctional Healthcare did not return phone calls requesting comment.

Petrona Juarez Tino, Tino Lopez's wife, now works at the local meat packing-plant and plans to rebuild her life in Nebraska. She said she has to stay strong and keep going for her daughter, and she wants answers about what happened to her husband. "He was still young," she said.

Robin Urevich is a journalist and radio reporter whose work has appeared on NPR, Marketplace, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Las Vegas Sun.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.