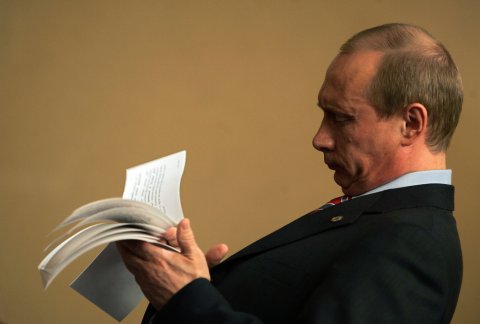

Muammar Gaddafi deployed a clever strategy to make sure he was always in the minds of leaders and ordinary citizens around the world: he pretended to be unhinged to confuse and frighten his adversaries. Lately Vladimir Putin seems to have adopted a similar strategy, appearing alternately depressed, out of touch with reality, or else disappearing altogether. Call it his antic disposition.

"There's a rationale in being perceived as unpredictable," says a recently-departed Moscow ambassador, who also knew Putin in St Petersburg. "Russian state television is aiding Putin by creating an atmosphere of collective psychosis. The Russian strategy is to scare the West by portraying Putin as unpredictable. If you've got a madman in power, a country's nuclear weapons take on a completely new dimension."

Indeed, in the past couple of years, Putin has gone out of his way to keep Russia's arsenal in the forefront of the public consciousness. According to Martin Hellman, an emeritus professor at Stanford and adjunct fellow at the Federation of American Scientists who specialises in nuclear risk, the West hasn't properly caught on to Putin's Armageddon game.

"Nuclear weapons are the card that Putin has up his sleeve, and he's using it to get the world to realise that Russia is a superpower, not just a regional power," he explains. "The Russians can turn us into ash in less than an hour." Less grandstanding with Putin is what is needed to prevent the madman game from ending in tragedy, Hellman argues.

The tactic has worked in the past. Gaddafi's nuclear development programme helped him efficiently bargain with the international community. North Korea's Kim dynasty uses the same sinister trick. In fact, a bit of perceived madness is essential to nuclear strategy.

"I call it the Madman Theory," US president Richard Nixon told his chief of staff, Bob

Haldeman, in 1969. "I want the North Vietnamese to believe that I've reached the point that I might do anything to stop the [Vietnam] war." In a classified 1995 report, the US military's Strategic Command recommends that "it hurts to portray ourselves as too fully rational and cool-headed . . . That the US may become irrational and vindictive if its vital interests are attacked should be part of the national persona we project to all adversaries".

Irrational and vindictive: that sounds a whole lot like the current Vladimir Putin. It's no surprise that foreign governments and intelligence agencies are frantically trying to figure out the enigmatic leader.

Several years ago, the Pentagon's in-house thinktank made a valiant attempt, concluding that Putin suffered from Asperger's syndrome. But the CIA is the undisputed leader of the discipline. Enlisting everything from diplomats' observations and intelligence reports to evaluations of the subject's public speeches and demeanour, the agency's Centre for Analysis of Personality and Political Behaviour created dozens of personality profiles of foreign leaders.

The Agency still produces such personality assessments. CIA spokesman Todd Ebitz explains: "Today these specialised analysts still provide policymakers with keen insights on foreign leaders, but they work in units throughout the Agency's Intelligence Directorate where they are integrated with analysts covering political, military, and economic issues."

So how do the CIA psychologists currently assess Vladimir Putin? The Agency won't tell. But according to professor Jerrold Post, who created and for many years led the personality analysis centre, the president "sees himself as a current-day tsar who's responsible for Russian-speaking peoples. But the person who's most important to him is Putin himself, not the Russian people".

The president's steely surface, argues Post, is a result of his being bullied as a schoolboy. "He took up martial arts so as not to be pushed around by other kids. We're seeing the same behaviour in his leadership." Nuclear warheads, then, are the world-leader equivalent of the bullied schoolboy's judo skills.

American billionaire investor Bill Browder is not an entirely dispassionate Putin observer, having been expelled from Russia and seen his upstanding lawyer die a mysterious death in a Russian prison. He has, however, known Putin since his early days in power. He calls Putin a "highly rational sociopath", who thought he had his domestic situation under control until President Yanukovich of Ukraine was brought down by the Maidan protesters. "Putin didn't want to end up like Yanukovich, and the only reason Putin invaded Ukraine is to create a massive distraction," he argues. Yanukovich's helplessness in the face of angry protesters mirrors that of Putin himself, who, aided only by KGB guards, defended the Dresden KGB office in the autumn of 1989 when East German democracy protesters demanded access.

Top politicians are largely cut off from contact with ordinary people. "That changes the mind of anyone," says a former friend of Putin's. "But Putin's KGB background makes him different. Other long-time leaders' psyches change the normal way, but his is changing the KGB way: everyone else is an enemy, you can only trust the KGB network. You become paranoid."

That paranoia fuels the madman game. "On one hand it's easy to say that Putin is crazy," reflects the former friend. "Because of him, now we're starting to think about nuclear war, which is completely different from two-three years ago. But on the other hand, his actions are not crazy at all. He'll do anything to stay in power, and using nuclear rhetoric is a means to that end. It's effective for him, but it's a mad strategy for Russia." That narcissist streak was visible long ago. A West German mole at the KGB office in Dresden became good friends with Putin's wife, Lyudmila, who told the mole that her husband beat her and was an incurable skirt chaser.

It is autocratic leaders such as Putin and Saddam Hussein who offer the most fertile soil for personality assessments, and when such leaders' countries steer into crises, these assessments become crucial. Jimmy Carter later pointed to the importance of the CIA's profiles of Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and President Anwar el-Sadat of Egypt, which highlighted Begin's love of details and Sadat's preference for big strokes as well as for having a "Nobel Prize complex".

But psychological assessments even of the most sophisticated kind will matter little if Putin decides to press the nuclear button. So what if it results in America retaliating by annihilating Russian cities? A narcissist leader who has a problem with empathy can't be expected to care. "The US is the world's only conventional superpower, but Putin can avoid humiliation by nuking us," argues Hellman. According to Browder, Putin is a thin-skinned man who can't back down, and Hellman suggests that the West should do as marriage therapists advise: admit one's own mistakes, thereby making it easier for one's spouse to admit his.

Another solution would be for Putin to step down, keep the $200bn fortune Browder estimates he's amassed and enjoy a pleasant retirement. In the past, discarded leaders have been received by sympathetic countries. Idi Amin found refuge in Saudi Arabia, as did Tunisia's Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. The Shah of Iran shuttled between reluctant hosts until Mexico offered him sanctuary. Ferdinand Marcos spent his final years in Hawaii.

But which leader would volunteer to host Vladimir Putin? His tenacious efforts to remain in power may be disastrous, but the madman strategy is completely rational.