Earlier this month, Vice President Mike Pence announced that the Trump administration was asking NASA, working with commercial space exploration companies, to prioritize sending humans to the Moon. There's not a clear timeline attached to that plan yet, and presidents have a long history of not quite managing to coax NASA into meeting the priorities they set.

But the U.S. isn't the only country with the Moon hitting its eye like a big pizza pie: India, too, has its sights set on lunar exploration. Their equivalent of NASA—the Indian Space Research Organization—is entering the last phase of testing of its Chandrayaan-2 mission, which is due to head to the Moon in March 2018. (The spacecraft is aptly named: Chandra means Moon in Sanskrit and Yaan means vehicle in Hindi.)

Chandrayaan-2 is an uncrewed mission with three components: an orbiter, a lander, and a rover. In particular, ISRO wants to use Chandrayaan-2 to study lunar dust. Dust bunnies on Earth are annoying, but they pale in comparison to lunar dust.

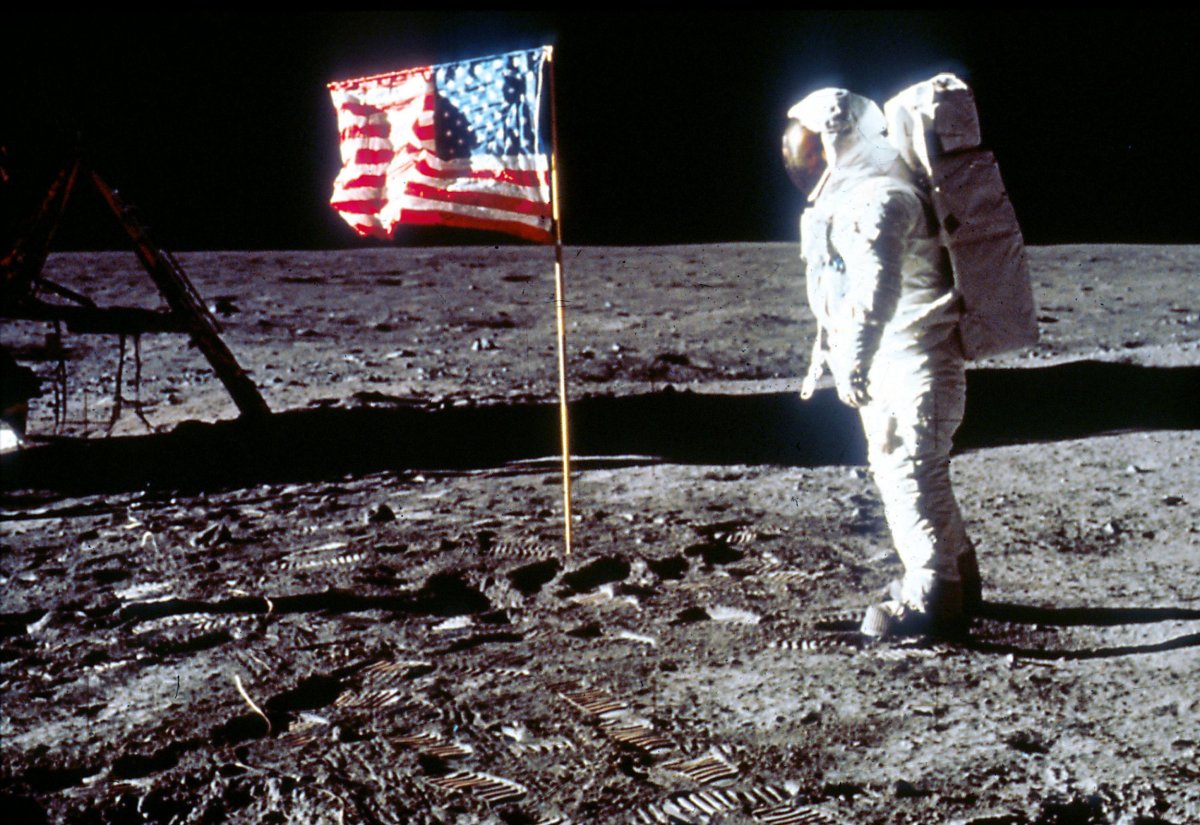

Lunar dust became infamous during the Apollo missions, when it snuck into the Apollo spacecraft and caused symptoms that mimicked terrestrial hay fever. It still prompts 40-page analyses of the spacesuits astronauts wore (which even today are still coated in the stuff). Because lunar dust is about half made up of shattered glass caused by meteorite impacts, it can do real damage.

And without an atmosphere on the Moon to keep the dust in check, it gets everywhere. So a key piece of Chandrayaan-2's mission is to study the force that moves the dust around, an envelope of highly charged particles circling the Moon's surface. Other tasks include taking the Moon's temperature near its poles. The mission is also developing a new way to land more softly on the Moon's surface. The entire project is supposed to cost just $93 million. Yes, with an M.

Although many Americans likely don't think of India as a spacefaring nation since it doesn't take part in the International Space Station, ISRO was established in 1969, less than a month after the first astronauts walked on the Moon.

Chandrayaan-2, as the name suggests, would be its second visit to the Moon. Its predecessor, an orbiter, circled the Moon 3,400 times and helped confirm there was water on it, but lost contact with Earth after less than a year, in August 2009. NASA tracked it down, still aimlessly pacing around the Moon, this March. India is also traveling to Mars and would like to explore Venus, in addition to a host of commercial space goals.

Russia and China also each have several trips to the Moon in the planning phases, but it's unclear whether this new space race will draw quite as much fervor as the 1960s race to the Moon.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more