Without Ingmar Bergman, cinema as we know it would be radically different. His early hits—Summer With Monika (1953), Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), Wild Strawberries (1957)—primed a global art house movement; his 1957 masterpiece The Seventh Seal opened the floodgates. In its wake, cinematic Pied Pipers like Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Michelangelo Antonioni and Nagisa Oshima, alongside the Swedish filmmaker himself, led a generation into film schools and sent droves of people to theaters.

But if The Seventh Seal altered the course of filmmaking, the career of Bergman—who died at age 89 in 2007 and whose centennial is celebrated this year—has a different epochal demarcation: pre- and post-Liv.

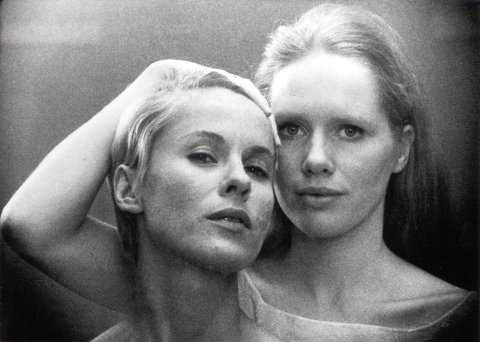

Bergman collaborated regularly with a number of actors: Max von Sydow, Bibi Andersson, Erland Josephson. But the supernatural link he had with Norwegian actress Liv Ullmann was something else entirely. Beginning with Persona in 1966, the two made 12 films together, including some of his most celebrated: Cries and Whispers (1972), Scenes From a Marriage (1974) and Autumn Sonata (1978). Ullmann's singular combination of radiant sensuality and the sort of steely intractability often associated with masculine roles, along with an instinctual connection with Bergman's words and direction, made her his ideal on-screen avatar. (He once called Ullmann "my Stradivarius.")

"There were a lot of things that I recognized in Ingmar, and he saw that and he knew that, and he knew we could do that without talking about it," Ullmann, now 79, told Newsweek.

Born in 1938 in Tokyo, where her Norwegian father worked as an engineer, Ullmann spent her early years in Toronto and New York, displaced from Norway by World War II. (Her grandfather was sent to the Dachau concentration camp, where he eventually died, for helping Jewish neighbors flee the Nazis.) At the end of the war, she returned to Norway with her mother and sister (her father had died of cancer while the family lived in New York) and, as a teenager, began acting. Stage roles as Anne Frank, Juliet in Romeo and Juliet and Margareta in Faust got her noticed, and eventually she moved into films.

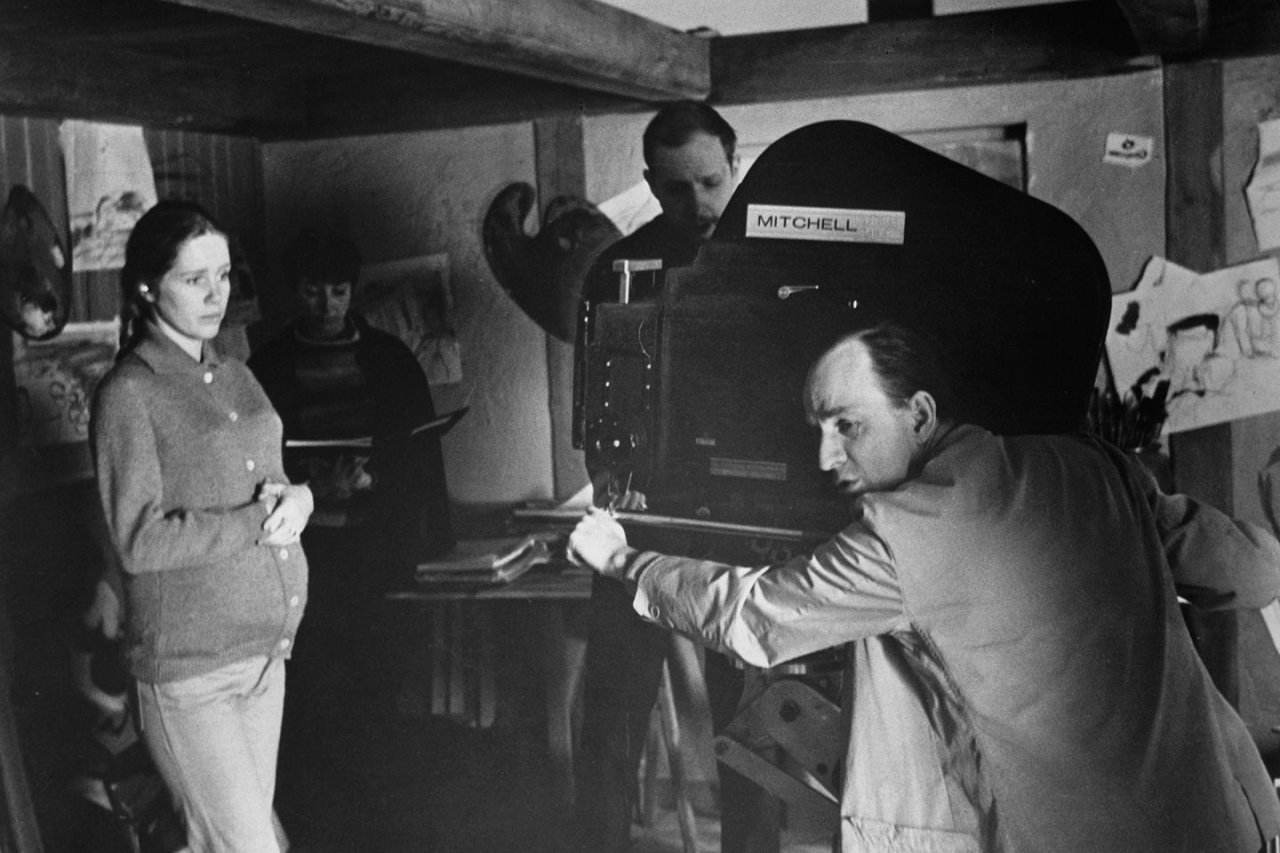

Ullmann attracted Bergman's attention in 1965 when he was casting Persona. A friend showed him a photograph of Andersson sitting next to "a young actress who was both like and unlike her," he wrote in his autobiography, The Magic Lantern. He was captivated by the women and their similarities—ideal for his dreamy psychodrama about duality—and when they began shooting on the tiny Swedish island of Farö, Bergman fell in love—with the location (he built his home there) and with Ullmann. "Liv and I were overwhelmed by passion," Bergman wrote.

The affair lasted five years and produced a daughter, Linn, but their professional relationship (and friendship) endured. She was—and is—synonymous with Bergman's films, and her intellectual, psychologically dense work with him earned her widespread acclaim and a Best Actress Oscar nomination for her suicidal psychiatrist in 1976's Face to Face. (She was also nominated for her work in Jan Troell's 1971 film The Emigrants.) And in the U.S. she became a major star, appearing on television programs like The Dick Cavett Show and on the covers of Time and Newsweek—a remarkable achievement for someone appearing primarily in foreign-language films.

But what allowed Ullmann to resonate—with Bergman and audiences—was her preternatural ability to express the filmmaker's humanism. It's a trait not typically associated with a man stereotyped as an aloof misanthrope, yet his career can be seen as one long confrontation with coldness and indifference, qualities Bergman abhorred. The scenes of desperate refugees crammed into a boat at the end of the exceptional anti-war film Shame (1968), for example, are eerily prescient and charged with empathy. And the evocative image of the knight playing chess with Death in The Seventh Seal is "about a man who's been cold all his life, and he just doesn't want to die before he has done one good thing for one other person," Ullmann said.

Perhaps the most sensational manifestation of the humanistic Bergman, though, belongs to Ullmann. In the rarely screened The Passion of Anna (1969), a kind of companion piece to Shame, she plays a woman rebuilding her life with lies after a tragic car accident. Halfway through the picture, she's given a nearly five-minute, single-take, close-up monologue. It's a bravura performance—Ullmann's cheeks flush, accentuating her impossibly blue eyes burrowing through the screen, as she spins a tale to deceive her lover and herself—and perhaps the ultimate expression of the actress and director's collaboration. But rather than Bergman's direction, Ullmann credits his screenplay for her performance. "I couldn't have made that blush. It was the words that made it happen," she says. "He was a really great writer, and I see that much more now than I even experienced then."

After The Serpent's Egg in 1977, Ullmann acted in just one more Bergman film, his last, 2003's Saraband, a sequel to Scenes From a Marriage. But in those years their collaboration shifted to Ullmann directing his scripts on camera and for the stage, giving her fresh insight into his material. He, in turn, cheered Ullmann's humanitarian work, which began in the early 1980s, aiding children and women refugees around the world through UNICEF and the International Rescue Committee.

That encouragement, and the patently Scandinavian brand of compassion that radiates from his films, revealed the Bergman that Ullmann knew and loved. And as the world marks his centennial, she sees an opportunity to slay his caricature. "Ingmar's not a solemn, dark, old-fashioned person," she says. "If you listen to what is being said in his films, he's a man who really, really wants to connect with the world. He's a man whose words now may be more important than they were when he wrote them."

Ingmar Bergman's Cinema: A Centennial Celebration continues through March 15 at Film Forum in New York. The retrospective series, organized by Janus Films, will play in other locations around the United States throughout the year.