The new Paul Thomas Anderson film (he dropped the "P.T." around the time of There Will Be Blood, though few in the media have chosen to follow suit) was, from the start, a thing. Anderson is Hollywood's current crown prince, the golden boy made good—a short film made when he was 23 got to Sundance; his first feature film, Hard Eight, was shot when he was 26 and featured Gwyneth Paltrow and Samuel L. Jackson at the height of their powers; and his 2007 film, There Will be Blood, is often considered one of the most important films of the first decade of the 21st century. Every new Anderson film is an event.

So when news leaked a few years ago that Anderson would adapt a Thomas Pynchon novel, his buzz turned into a roar; if anyone can top Anderson in that crucial Venn diagram of fanboy worship and critical acclaim, it's Pynchon, whose novella The Crying of Lot 49 launched a million secret-society stick-and-pen hipster tattoos, and whose Gravity's Rainbow is hailed as one of the American literary masterpieces of the 20th century despite the 1974 Pulitzer Prize committee calling it "unreadable," "turgid," "overwritten" and "obscene."

Pynchon, to put it mildly, keeps to himself. He is famous for his media reticence—there have been no photos taken of him in decades, and he does not grant interviews. And yet, he is far from a Luddite. His fiction suggests a man infatuated with pop culture. He has, for example, appeared on The Simpsons, drawn with a paper bag over his head to mock his public persona (or lack thereof). His 2009 novel, Inherent Vice, is loaded with all the latest and greatest, from both the story's 1970 setting (the Manson trial, surf rock) and its 2008 writing period (the book has shades of the decade's housing crises). And rumors of the invention of what would become the ubiquitous Internet are threaded throughout. But despite their ability to keep a metaphorical finger on the cultural pulse, not to mention the presence of copious amounts of violence, sex and drugs, none of Pynchon's books have made it to the screen—until now.

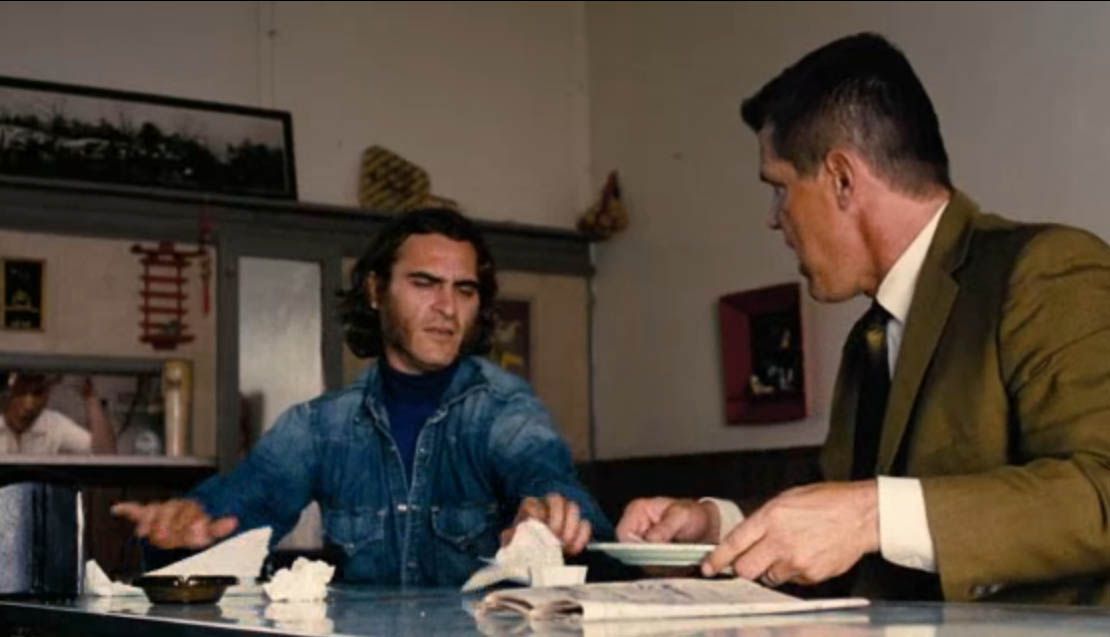

Anderson has taken Inherent Vice, which may be best described as a collision of Raymond Chandler and Ken Kesey, and turned it into a juicy piece of Oscar-bait, an ensemble film featuring superstars (Joaquin Phoenix, Reese Witherspoon), buzz-worthy lesser-knowns (Michael K. Williams, Joanna Newsom), opulent cinematography and a script dense with humor, drama and deep thoughts.

It makes sense that these two auteurs would collide. Anderson and Pynchon share a unique (and uniquely postmodern) talent: They both can harness overripe symbolism that in the hands of lesser artists would scream "pretentious student thesis": Gravity's Rainbow is built around the twin peaks of one man's prophetic erection and a V-2 rocket; Anderson's 1999 film Magnolia features a rainstorm of frogs.

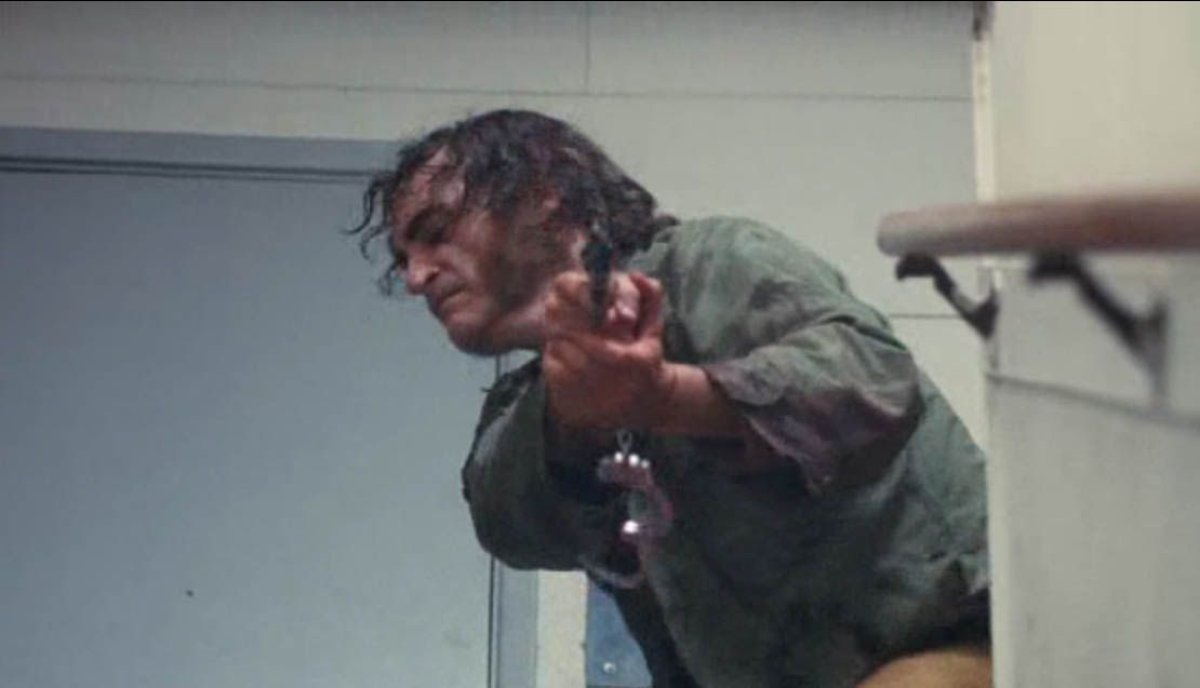

In Inherent Vice, everything is a symbol, and so nothing is; "to see patterns in the chaos is to be deluded," says private eye ("gum sandal") Larry "Doc" Sportello (Phoenix), the film's protagonist. And so it would be pointless to rehash the plot of this noir(ish) story set in a made-up SoCal hippie(ish) beach-bum, Technicolor (lost) paradise. Doc doesn't so much go from point A to point B as he becomes buried under ever deepening snowdrifts of unreliable personae, shady and long-tentacled organizations, and obtuse conversations overladen with kitschy Age of Aquarius philosophizing.

Don't worry if you can't keep track. Neither could Anderson, and he clearly didn't care. "I saw The Big Sleep, and I realized you can't follow any of it, but that didn't matter," Anderson said at a press conference following the premiere of Inherent Vice at the New York Film Festival on October 4. There is a tale (whether true or apocryphal is unclear) that Raymond Chandler didn't know where his own plot led; supposedly, the screenwriters adapting The Big Sleep for Howard Hawks's 1946 film version called Chandler asking who killed one character in the story, and he said he had no idea.

Chandler's book (and the films based on it) and Inherent Vice are fine examples of a certain form of storytelling, common in noir, where plot matters little and atmosphere and character are paramount. In Inherent Vice, atmosphere is driven by the visual style—which departs from Anderson's typical cool blues for the more washed-out nectarines of SoCal—and, even more prominently, by the voice-over narration performed by singer-songwriter Newsom in the role of Sortilege. She's a sort of psychic His Girl Friday, "in touch with invisible forces," who provides the story with a second layer of ambience in a honey-sweet timbre shaded with nostalgia that recalls Linda Manz's work in Terrence Malick's Days of Heaven, or Candace Evanofski in David Gordon Green's George Washington.

"For a long time, I was told if you used voice-over, that's a no-no," said Anderson, in response to a question about the Sortilege character. "But all of my favorite films use a narrator and narration, and I was always paranoid to do it until now, where there was so much good stuff that that character could say that was from the book, that seemed helpful to the story and wouldn't step on it or irritate it or subtract from what was going on, but hopefully add to it at its best."

Both the novel and film version of Inherent Vice are loaded with symbols that could easily be construed as kitsch: Ouija boards, beaded curtains, chocolate-covered bananas and molded plastic house phones don't seem to do much besides evoke a sentimentality for another time. The voice-over seems to fall into this category, spewing New Age-isms that are evocative but feel light and lost, easily washed away by one of the many Pacific waves that crash on the beach just a few hundred yards from Doc's driveway.

But it may more be valuable to think of kitsch, as the novelist Milan Kundera did in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, as "the stopover between being and oblivion." And that's squarely where Inherent Vice sits. Doc is Lebowski if The Dude didn't even care about his living room rug. For most of the film, Doc's sense of mission is lax and meandering—it's unclear why he stays involved in what becomes an ever more dangerous adventure. Ultimately, the only way to understand the film is as a form of joyful nihilism: the conspiracy is inescapable—Doc can't do anything about what's happening to him—so why not join in the fun?

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Elijah Wolfson is a Senior Editor at Newsweek, where he writes and edits on science, health, technology and culture. He is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.