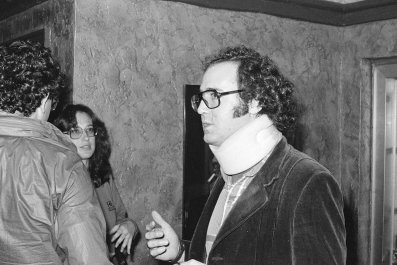

There aren't many students at Sofia University who wear a hijab, so 20-year-old Aishe Emin's stands out. Since she moved to the Bulgarian capital two years ago, her veil has attracted unwelcome attention. But in recent months, she's received more hostile comments and stares. Her husband, Mustafa, who also attends the university, has a beard and prays regularly; some of his fellow students, he says, consider him "radical" for doing so.

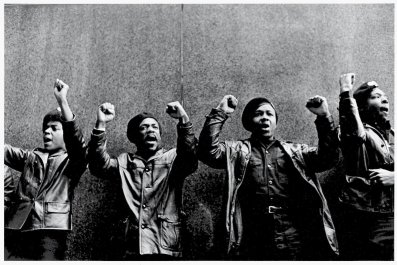

The Emins are part of Bulgaria's native Pomak Muslim community. This group has faced persecution before, when fascist and later communist governments were in power. But since the recent Islamist attacks in France and Belgium, she and others have complained of a new backlash against Muslims. Most politicians in Europe have condemned the recent rise in Islamophobia, but right-wing parties in many EU countries have fueled the fear and hatred Muslims encounter on a regular basis. The Patriotic Front, a right-wing Bulgarian party that's in the ruling coalition, has introduced a series of laws that critics say would make discrimination against Muslims part of the country's legal code. Parliament has already approved one of them, a ban on women wearing veils that even partially cover their faces.

If Bulgarian lawmakers approve the rest of the vaguely worded legislation, foreign citizens would not be permitted to deliver religious sermons; foreign funding for all religious denominations would be suspended; it would be mandatory to use the Bulgarian language during all religious services; and "radical Islam" would be considered against the law, among other things. (The legislation defines adherents of "radical Islam" as those who call for the creation of an Islamic state, forcefully impose Islamic norms on others, spread holy war or raise funds for an Islamist terrorist group.)

Other countries in the European Union, including France, Latvia and Belgium, ban face coverings, but Bulgaria's proposed law prohibiting "radical Islam" would be the first within the EU. If passed, the legislation would mainly affect Muslims whose families have lived in Bulgaria for centuries—ethnic Turks, Pomaks and Roma.

Analysts say there isn't a single known case of a native Bulgarian Muslim joining a Middle Eastern extremist group. But that has not stopped the country's right-wing politicians from advancing one of Europe's most anti-Muslim agendas.

Yulian Angelov, a parliament member for the Patriotic Front, says his party is simply trying to prevent Bulgarian Muslims from becoming radicalized. The proposals, he says, would allow authorities to take early action against outsiders who plan to indoctrinate the local population and promote violence. "We all remember the bombing [in Burgas]," says Angelov, referring to an attack on a bus carrying Israeli tourists in that Bulgarian town in 2012. The investigation found that three men with Western passports and links to the Lebanon-based Hezbollah were behind the bombing. No Bulgarian nationals were implicated in the attack, which killed seven people, including the bomber. "We have to take measures," says Angelov. "We see that there are constantly terrorist attacks. We see millions of illegal migrants conquering Europe."

Critics, however, say the new laws would not only ostracize Muslims but also infringe on the rights of other religions, including Judaism and Christianity. The Bulgarian Grand Mufti's Office and the Bulgarian Catholic Church have condemned the measures, as has the Central Israelite Religious Council in Sofia. "The proposed changes in the Law on the Religious Denominations are one more step in the retreat from the democratic principles," the council said in a statement.

Another question is how the government will enforce the law. Many Islamic scholars say establishing a state run on the basis of Islamic law, along with jihad, a Koranic concept for struggle (and not necessarily a physical or violent one) in God's name, are among some of the most fundamental ideas in Islam. "How can we legally define one of [these ideas] as 'traditional' and another as 'radical'?" says Simeon Evstatiev, an associate professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic history at Sofia University. "Such a definition would create chaos among prosecutors, lawyers and judges, who will need to be competent in theological issues in order to work on such court cases. This—to put it mildly—is absurd."

Mihail Ekimjiev, a Bulgaria-based human rights lawyer, says the ambiguity of the term "radical Islam" could permit legalized persecution of Muslims. In his opinion, some of the other provisions in the proposals violate EU and human rights law. "Religious institutions have to be relatively autonomous from the state," he says. "The possibility of their being pressured with frequent checks opens the way for state repression against them."

Aside from the "burqa ban" parliament has preliminarily approved another Patriotic Front proposal—the criminalization of "radical Islam." But the legislation is still awaiting amendments and a final vote for approval.

Fearing recriminations, most Bulgarian Muslims aren't speaking out in public about the proposed laws; they're waiting to see what happens in parliament. Meanwhile, acts of hooliganism against Muslims have become more common, says Jalal Faik, the secretary general at the Grand Mufti's Office in Sofia. In August, vandals defaced a Muslim hearse in the northern city of Pleven with graffiti that read: "Murderers," "Islam is destroying Europe" and "You committed genocide against Bulgaria."

If the legislation passes, Faik predicts Bulgaria's Muslims won't stay silent for long.