Updated | Since the 9/11 attacks, the feds have won more than 500 terrorism convictions. In nearly half of those cases, confidential informants played a key role in bringing down the alleged bad guys. Of course, snitches have been around since Judas flipped on Jesus. That they are crucial to making cases is beyond debate. How reliable they are is not. Beyond the scattered community of grieving parents, civil liberties lawyers and a few crusading journalists, however, little attention has been paid to the abuses of the system in which the FBI coached informants to build flimsy cases against defendants.

Now comes (T)error—the parenthesis is supposed to emphasize error—an astounding documentary that casts serious doubt on the rectitude of some of the government's cases. Up to one in 10 has been tainted by informants who seduced their marks into plots dreamed up by the FBI, according to Trevor Aaronson, author of The Terror Factory: Inside the FBI's Manufactured War on Terrorism. What filmmakers Lyric Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe have managed to do is create an upside-down version of Cops. By trailing along with a key counterterrorism informant who invited the filmmakers into his demimonde—without telling his FBI handlers—the documentary reveals how snitches persuade their marks to move from idle talk about jihad to contemplating—if not actually doing—something more serious. The film drew raves at Tribeca and Sundance last year, but it got a shot at a wider audience when it debuted February 22 on the PBS series Independent Lens.

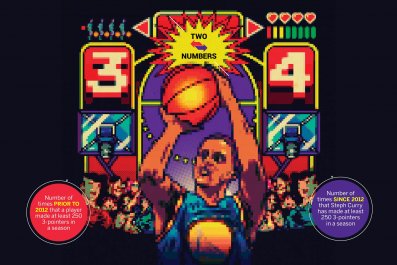

The star of what amounts to this noir home movie is Saeed Torres, a 63-year-old former Black Panther and ex-con who is working as a middle school cook, serving hot dogs at a basketball game, as the film opens. The flabby, graying Torres, cover name "Shariff," claims he made hundreds of thousands of dollars as a counterterrorism informant in the first years after the September 11, 2001, attacks, but when co-director Cabral encounters him in 2005, business has dried up. Torres and Cabral had been neighbors in Harlem a few years earlier, when she was a budding photographer in New York. At the time, she thought Torres was a legal aid worker, but that was just his cover job. Later, Torres not only unburdens himself to Cabral, telling her he's an FBI informant, but also agrees to let her and Sutcliffe into his dark ops.

It remains a mystery why. "It didn't entirely make sense to us either, at the time," said Sutcliffe, the film's cinematographer and co-director, in a 2015 interview with Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman. "We said, 'Why would this person agree to participate in this film?' But we didn't want to question that."

The result is a compelling, Kafkaesque tutorial arguing that at least some of the Justice Department's busts have been bogus. Torres's first victim in the film is Tarik Shah, a Muslim convert and highly regarded modern jazz bassist who had toured with the likes of Ahmad Jamal, Art Taylor and Betty Carter. When Torres meets Shah, he's $80,000 in arrears on his child support, which triggered the loss of his passport, and grousing about Muslims being killed in Afghanistan. Pretty soon, Torres and an FBI counterterrorism agent coax Shah, a martial arts expert, into a made-up plot to train Al-Qaeda recruits at a warehouse in Queens. The clincher comes when he and another man targeted by the FBI agree to swear an oath of loyalty to Al-Qaeda.

"It was like a bait on a hook, and he bit into it," Torres tells the filmmakers. "He said, 'I'll do anything,' and that's when they knew they got him." In 2007, Shah was sentenced to 15 years in prison for providing "material support" to Al-Qaeda. His only misstep was swearing an oath.

"Tarik may be guilty, but you know what? Of talking," Shah's mournful mother says in the film. "In the whole thing, there was nothing about any weapons—no bombs, nothing. Just talk."

The real drama in (T)error unfolds when Torres, now desperate to make more money, heads off to Pittsburgh to get close to Khalifa Ali al-Akili, born James Marvin Thomas Jr., a scuffling, pasty-faced 33-year-old whose jihadi screeds on Facebook have drawn the FBI's attention. Driving south in his beat-up car, Torres sees himself as a kind of poor man's James Bond. "I don't like to be called an informant," he says. "I'm a domestic operative...a spook."

His FBI handler pushes him hard to make a terrorism case against Akili. (In a wonderful turn of fortunes, the filmmakers record the telephone conversations between the FBI man and his snitch.) It doesn't go well. Torres befriends his mark, but after a number of strained meetings with Akili, Torres tells his FBI handler there's nothing there. "He's not a terrorist. He's not even a pseudo-terrorist," he says. "He's nothing but an oxymoron.... He won't even throw rice at a wedding."

But the FBI wants a case. Unfortunately for the bureau, it doesn't take long for the mark to suspect that "Shariff" is an agent provocateur. Proof comes when Torres leaves Akili alone for a few moments in his car, and Akili sees an envelope on the dashboard from the Social Security Administration. Of course, it's addressed to Torres, not "Shariff." Akili reaches out to Stephen Downs, who runs something called Project Salam, which is dedicated to exposing the prosecution of Muslims "who were in fact innocent of any crime." And in a rank double cross, the filmmakers now cast Akili in their cinema verité too, without telling Torres. As journalism, it's astounding. "He had caught the FBI trying to catch him," says Downs, a former chief attorney with the New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct. "I've never quite seen a case like that."

It's also deeply unsettling. When the FBI learns that Downs is going to showcase Akili in a Washington, D.C., press conference, it swoops in and arrests him. After a flurry of sensationalist TV stories about the arrest of a local "terrorist," of course, the spotlight moves on. Few reporters are around when the terrorism case against Akili collapses and the hapless defendant pleads guilty to a gun charge. (He'd posted a picture of himself holding a rented weapon at public rifle range, a technical violation of his parole from a drug conviction.) Packed off to prison, with his wife and daughter evicted from public housing and deported to the U.K., Akili is serving a nearly eight-year sentence.

The FBI continues to pile up cases like that one. On February 8, a Minneapolis informant went public with a complaint that the feds were racking up impressive-looking statistics by going after low-level terrorist fantasizers or wannabes instead of kingpins. Tony Osman, née Mohamed Ali Osman, charged on Fox affiliate KMSP that "they want to get as many convictions as possible, while leaving the high-level radicalizers free." After Osman went public, police raided his home and seized marijuana plants that he says his handlers knew about all along. He believes the raid was retaliation by the FBI.

Hugh Handeyside, a former CIA analyst who is now a staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union, calls (T)error a "tremendously important documentary" because it "humanizes" the process in which so many lives are ground up in the government's counterterrorism machinery.

Karen Greenberg, director of Fordham Law School's Center on National Security, praises the film for shining a spotlight on abuses in the system. Greenberg, author of the forthcoming Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State, also says there is reason to believe the government may be changing its ways. Even as it faces a new threat from homegrown extremism whipped up by the Islamic State group, she tells Newsweek, the FBI "now seems to take more seriously the idea of early intervention" with young people seduced by ISIS's siren songs, "rather than enticing them to bigger and bigger crimes." The result, she says, has been plea deals and prison sentences that are "significantly lighter."

That's another way to save lives. But don't count on the government throttling its machinery. It has good reason to fear another ISIS-inspired attack. On February 8, the director of national intelligence, James Clapper, told Congress that homegrown extremists probably will "continue to pose the most significant Sunni terrorist threat to the U.S. homeland in 2016." And this year's presidential candidates, at least on the Republican side, are vowing to take harder measures to prevent more attacks.

Americans want the FBI out there. They need the FBI out there, to paraphrase Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men. They want the FBI and other counterterror agencies to do everything they can to thwart another attack. And that means informants will remain on the front lines of stopping plots, even if it means ginning up a few along the way.

This story was updated to include a reference to Trevor Aaronson's book and more information about Khalifa Ali al-Akili.