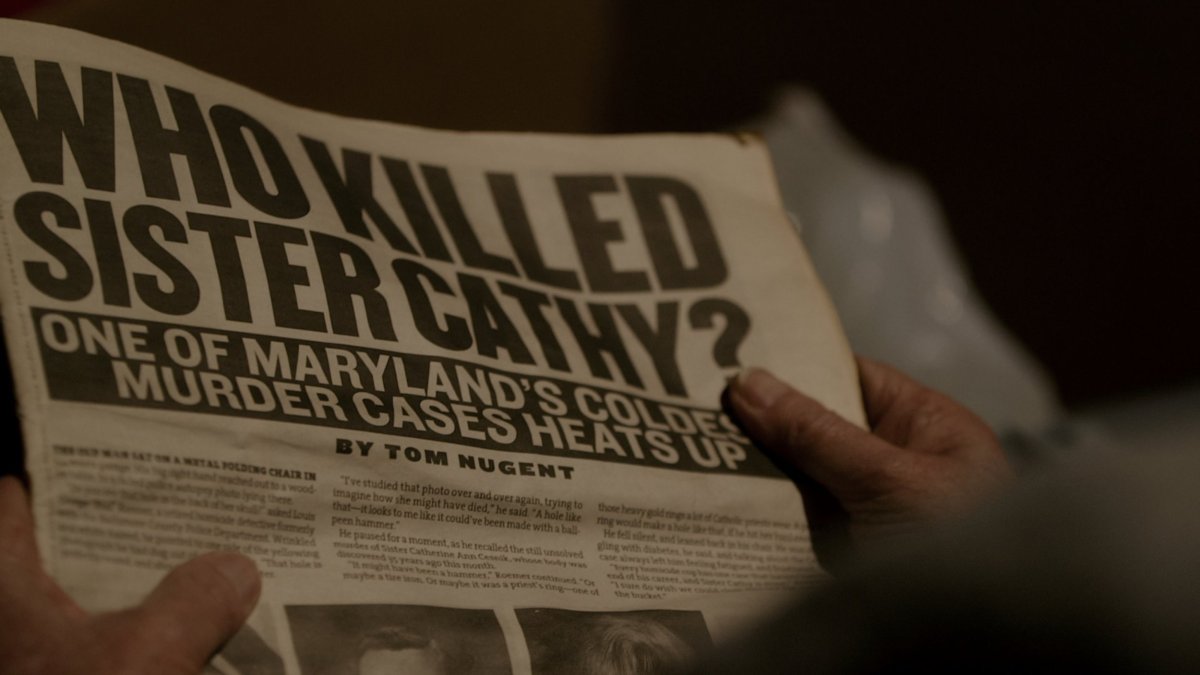

From their living rooms in Baltimore, two retired women spend each night poring over the latest contributions to a Facebook group they manage in the hope of answers. Who killed their beloved high school English and drama teacher, Sister Cathy?

For the last four years, Abbie Fitzgerald Schaub and Gemma Hoskins have been piecing together an impressive jigsaw, with the help of a network of fellow amateur investigators, that could finally solve this nearly 50-year-old cold case. "I think we probably have more information than any police officer or detective has had on this case—ever," says Hoskins in the first episode of the new Netflix series The Keepers, launching Friday.

The premise of the show may seem like a work of surreal fiction, but it is very much a real story. The Keepers is a seven-part docuseries directed by Ryan White that treads ground similar to Netflix's earlier hit Making a Murderer. At its heart is an equally attention-grabbing murder case that remains unresolved, as well as the question of potential miscarriages of justice by the very institutions meant to protect people. But in many ways, The Keepers is far darker, more insidious and more heart-wrenching than Murderer.

On November 7, 1969, 26-year-old Sister Cathy Cesnik disappeared after a shopping trip in Baltimore. Cesnik, by all accounts from the former students interviewed by White, was a smart, kind and compassionate teacher at Archbishop Keough High School, a now-defunct Roman Catholic girls' school that was part of the Archdiocese of Baltimore. She was younger and more relatable than the other nuns who worked there. One student remarked how Cesnik's imaginative teaching techniques helped her enjoy Shakespeare.

Cesnik's dead body was found two months later on January 3, 1970, at a rubbish dump in Lansdowne, Baltimore. A homicide investigation was begun and remains open to this day.

Cesnik's murder, however, is only the entryway into a larger scandal that people in positions of authority have gone to great lengths to conceal, White, the filmmaker, tells Newsweek. "The series has really evolved into something much darker and a deeper web than what we thought we were looking into at the beginning—the murder of Cathy," says White. "Now, looking back from the finish line, it was one point in a much larger and longer crime that's happening in Baltimore."

The Jane Doe Mystery

In the first episode of The Keepers, Schaub says: "The story is not the nun's killing—the story is the cover-up of the nun's story."

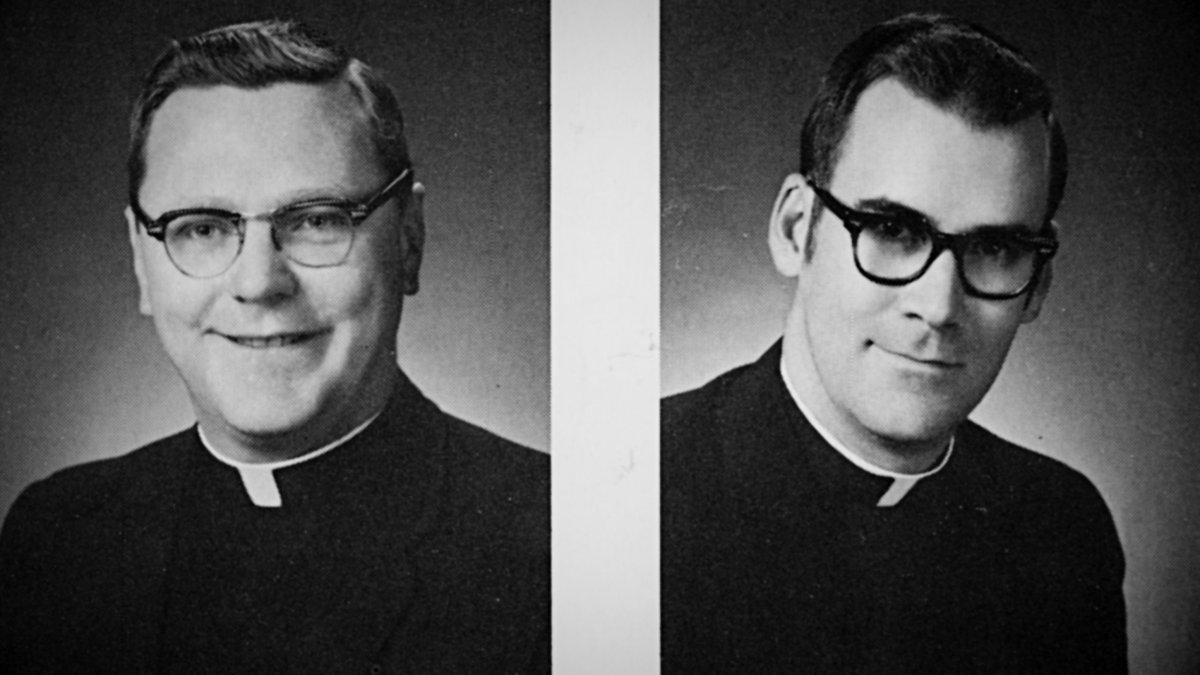

As the documentary unfolds, White paints a compelling theory: Cesnik was murdered because she had uncovered a secret at Keough and threatened to expose it. Cesnik, according to The Keepers, alleged that the school's chaplain and guidance counselor, Father A. Joseph Maskell, had sexually abused vulnerable students.

Although these events occurred in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the first allegation did not surface until 1992, when one victim, who had suppressed memories of her high school anguish, began remembering what happened and reported Maskell to the Archdiocese of Baltimore. The archdiocese asked her to corroborate her story by bringing other victims forward. She refused.

In 1994, the victim became Jane Doe in a $40 million civil lawsuit against Maskell, the archdiocese and others. Doe claimed she was repeatedly raped by Maskell in his office under the guise that he was cleansing her of her sins. She said she had confided in a teacher, Cesnik, who told her she would "take care of it." Cesnik wound up dead. After the nun's body was dumped in a discreet wooded area, Doe alleges Maskell drove her to the site, showed her Cesnik's body and said: "You see what happens when you say bad things about people?" The story swept Baltimore and reignited what had become a cold case.

The lawsuit prompted more women who attended Keough at the time to come forward, each with similar stories to Doe's: Maskell would target girls who had had a traumatic experience in their childhood, like sexual abuse, or a troubled youth. He would ply them with alcohol and cigarettes, and, some allege, even drug them. He would tell them they were sinful and he had to pray for them so God would forgive them, a pretense to abuse them. And Maskell allegedly wasn't alone. Father Neil Magnus, a fellow priest at Keough, is also accused of abusing students, Doe among them. More than one woman, including Doe's co-plaintiff in the lawsuit, Jane Roe, said Maskell invited other men, including police officers, to take part in the abuse both in his office at Keough and off-campus. Maskell was well connected. In addition to serving as chaplain at Keough, he was also chaplain for the Baltimore County Police Department and Maryland State Police.

Jane Doe is Jean Hargadon Wehner. She revealed her identity in 2014 to the shock of friends and former schoolmates who were oblivious to her alleged abuse. White has a personal connection to the story: His aunt attended Keough and was a student of Cesnik's. She was also friends with Wehner, and they are still close. White saw potential for a documentary.

"My aunt introduced me to Jean over email," says the filmmaker. "I flew out to Baltimore, and I met her; we had a five-hour conversation at her dining room table. I left the dinner that night saying, 'I want to make this with her. She's believable, she's credible, and it's incredible, and I want to be part of telling this with her.'"

It took three months of deliberation between Wehner and White to get her to agree to take part. Production began in the fall of 2014, just months after Wehner went public as Jane Doe.

From there, White gathered his cast of characters: Hoskins and Schaub, the former students turned Facebook detectives; Tom Nugent, a veteran journalist who'd followed the case since the early 1990s; and even a former police officer who is referred to as "Deep Throat," like the informant in the Watergate scandal. "We met Gemma when we went to Baltimore; she drove us around, showing us all the hot spots," says White. "I fell in love with Gemma as a character right away—it was such a unique way to tell a true crime story through the eyes of the murder victim's former student who really looked up to her."

The core of the story, however, is the women who were allegedly abused by Maskell. Wehner's pained account of events in the second episode of The Keepers is echoed by similar stories from Teresa Lancaster—Jane Roe in the 1994 lawsuit—Donna Von Den Bosch and Kathy Hobeck. Hobeck, like Wehner, turned to Cesnik for help. She claims she saw the murdered nun the night before she disappeared.

"The Keepers is a woman's story, and as a man, I'm very privileged to have been part of telling that," says White. "I hope it resonates, and I hope we ask questions. This isn't just a story that happened in 1969. Women are forced to suffer in silence all the time after their sexual assaults. If we can create a dialogue, and Jean, Teresa, Donna and the female survivors in my documentary can be a voice for that, I will be very proud."

'A Dark Abyss'

White, and his executive producer, Jessica Hargrave, and cinematographer, John Benham, shot around 750 hours of footage in Baltimore. The filmmaker initially envisioned a feature-length film, but that soon became improbable because "the story was constantly growing in scope. Every time we went to Baltimore, we would meet new people with a new version of the truth, or a new survivor of Father Maskell's. It seemed like this dark abyss."

During production, a new wave of true-crime storytelling was born—the podcast Serial, HBO's gripping The Jinx and, of course, Netflix's own Making a Murderer. White was inspired to tell his story over a longer format. "I first visited Baltimore even before Serial came out," he says. "There were no predecessors for long-form documentary storytelling for the most part." As these other examples captured the zeitgeist, White says, distributors were more open to a longer, more nuanced docuseries—Netflix initially commissioned six episodes of The Keepers. The final count is seven.

White admits that at times he too felt the danger of digging into a "story that deliberately was silenced."

"All throughout production we felt the tension," he says. "There were many times we would look at each other in certain situations and not feel comfortable, or feel like we might be endangering someone because you would feel the tension of people not wanting you rooting around."

But ultimately, White, Hargrave and Benham kept persevering. "What we would always say to each other in those moments was, we were part, side by side, of telling these victims' stories, and these women so brave speaking up," he says.

Two powerful institutions have had very differing degrees of involvement in The Keepers. The Archdiocese of Baltimore, which many involved in the case have accused of conspiring to cover up Cesnik's death and Maskell's abuse, tells Newsweek it answered six questions that White and his team presented in writing. The archdiocese wasn't given advance copies of the series.

The archdiocese removed Maskell from the church in Baltimore in 1994, after Wehner, Lancaster and more victims came forward. Although no charges were ever brought against Maskell, a spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Baltimore says he was removed because the church believed there were "credible allegations against him." Maskell fled the U.S. and resettled in Ireland in 1994. He died in 2001.

Since 2011, the archdiocese has negotiated payouts to victims of Maskell, the spokesperson says, because "we felt we had a moral responsibility to respond to the fact that they were abused by someone representing [the church]. It was important for us to do what we could to promote their healing." In January, Nugent, the journalist featured in the documentary, reported that Wehner had reached a $50,000 settlement; Lancaster settled for $40,000 in 2014. In total, 16 payments have been made, the archdiocese confirms to Newsweek.

The Baltimore County Police Department, the other key institution accused of a cover-up, had a more active role in the documentary. White interviewed the current cold-case detective assigned to the case, Gary Childs; the officer appears in episodes six and seven. "I give the Baltimore police a lot of credit for showing some transparency," White says.

"Clearly, there's been failures over the last 45 years, and police officers were involved in the rapes of these girls, so there was motive to cover up the sexual abuse and the murder. However, 45 years later, I believe the detectives now. I don't think the conspiracy of silence has filtered down to them," White says.

Justice and Closure

When The Keepers hits Netflix Friday, it's likely to have the same immediate impact as Making a Murderer did in 2015—sparking social media discussion, months of headlines and a healthy, or perhaps unhealthy, measure of armchair detective work.

White's storytelling—a mix of firsthand interviews, archive footage and artsy black-and-white reconstructions—is engrossing, and the cliff-hangers at the end of each episode make it inherently binge-worthy. But will the show answer its marketing tagline: "Who killed Sister Cathy?"

"I began this by thinking, We're not out to solve a murder—it's unlikely to solve a murder that's 45 years old, and all the evidence and oral history has been deliberately buried," says White. "By the finish line, I'm thinking this is not too late to be solved."

There have been various developments recently that White is optimistic about. In February, the Baltimore County cold-case team exhumed Maskell's body to obtain a DNA sample and compare it to what evidence remains from the crime scene where Cesnik's body was found. On Wednesday, the police department confirmed there was no match. A spokesperson says that doesn't necessarily clear him of involvement in the murder.

Also in February, an unidentified woman told CBS Baltimore she believed her husband, a friend of Maskell's, committed the murder. She remembers "he had blood all over his white shirt" when he returned home the night Cesnik was killed in 1969. CBS also reported the man "may have been recently questioned by police."

"I think it's a promising turn of events that the Baltimore police are finally taking [Maskell] seriously as a suspect," says White. "But on the flipside, it begs the question why he was never taken seriously as a suspect when he was alive, of either the murder or the abuse. He died a free man."

A new thread developed this week in the days before The Keepers' release. A woman came forward to say she'd been sexually abused by a Baltimore County police officer "associated with the Cesnik case and with Maskell," a spokesperson for the department says. The officer is now dead. The woman, the department says, refused to be interviewed by police.

White, however, has no plans to keep documenting the case beyond his seven-episode series. "Jean [Wehner] was my central figure throughout the process; by the end of episode seven, I felt like we had reached a stopping point in the story I was telling," he says. "Jean and I looked at each other and said, 'It's time to release this to the world and see what happens.'"

"There's definitely more justice to be had," White says, "more answers to be had and more accountability, because there's never been that."

The Keepers airs on Netflix from May 19.

If you have any information about this case and wish to speak to Newsweek, please email the author of this article: Tufayel Ahmed, t.ahmed@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.