Timothy Snyder stood at the front of an enormous classroom and warned his students that resistance against the Nazis didn't look much like what was depicted in Casablanca. He recommended that they watch the 1942 film starring Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart, but keep in mind that the romantic picture it paints in black and white—that resistance was French, that everyone was beautiful, that it unfolded with a series of heterosexual relationships, and, above all, that there was one, singular resistance—doesn't reflect the historical realities.

"This is a topic, perhaps as much or more than any other topic we'll cover in class, that is just soaked in myth," he told a lecture hall full of undergraduates in early March at Yale University, where he is the Richard C. Levin professor of history. Snyder bent his tall frame toward a microphone jutting out of a podium, his voice echoing against the tall windows and wood-carved ceiling. If you want to bask in that cinematic rendering of resistance "and you haven't seen it before, go see Casablanca," he said. "It's a wonderful film."

Related: The Anti-Trump Resistance: Lawyers Lead the Fight Against the White House

From there, the rest of his popular "Eastern Europe Since 1914" course lecture departed sharply from Hollywood and plunged into the intricacies of real resistances in Eastern Europe during World War II, though Snyder continued to lace in a few jokes. When he mentioned the Proletarian Shock Brigades that formed in Yugoslavia, he quipped that "to you it sounds like a punk band that broke up 23 years ago."

The students laughed and leaned forward over their notebooks, trying to keep up with Snyder's rapid speech. As a rule, Snyder doesn't talk about politics in the classroom and he doesn't change his history lectures, "not a word," based on what's happening in the news. But the students who had been keeping an eye on his writings and public appearances outside the lecture hall would have known on that chilly Thursday afternoon that his thoughts about opposing totalitarian rule extend beyond the confines of midcentury Europe to the present day. Earlier that week, he had released a new book, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From the Twentieth Century. It's now a best-seller.

"History does not repeat, but it does instruct," reads the first line of the pocket-sized book—a slim volume more like a guide than a tome of historical scholarship, though Snyder drew on 25 years of research and writings. "The European history of the twentieth century shows us that societies can break, democracies can fall, ethics can collapse, and ordinary men can find themselves standing over death pits with guns in their hands. It would serve us well to understand why.… Americans today are no wiser than the Europeans who saw democracy yield to fascism, Nazism, or communism in the twentieth century. Our one advantage is that we might learn from their experience. Now is a good time to do so."

Snyder has spent the past few months in the public eye, continuing his streak as one of the most recognizable history professors in the country. Even people who have long since left college or who would never have considered signing up for two semesters of lectures on Eastern Europe (he also teaches a pre-1914 course) might know Snyder from his recent publicity, including an appearance on HBO's Real Time With Bill Maher.

During his five-minute segment, he made a few jokes, abiding by the implicit rules of that show's format, but he also had a serious message. He was impatient to share a reduced list of "three [lessons] and a bonus," imploring viewers not to obey in advance, to defend institutions, to beware of the use of an emergency to suspend civil liberties and to believe in truth. He said we should view the dismissal of truth as a "direct line to killing democracy." When his host, Bill Maher, read a semi-serious list of things about Donald Trump that reminded him of what he called "Third World dictators," Snyder said dryly, "I'm not going to laugh at any of that," and reiterated that, to him, this all smacks of the 1930s. "And what we have to remember about the 1930s," he said, is that "we think of Hitler and Stalin as supervillains. But they're not. They could only come to power with some form of consent."

Snyder's students—and many Americans tuning into Maher's show or reading the professor's latest book—"are now interested in the problem of regime change and have now recognized the fragility of democracy as something which isn't just exotic," he says. "They get that now."

An American in Eastern Europe

"We have enormous potential for complacency in this country…because we think it's never been different," Snyder says. In the past several months, he's heard from Holocaust survivors, immigrants from Soviet Russia, Jews who left Poland after 1968 and others who are "jumping up and down because they see signs of fundamental change. But Americans, they don't have those kinds of intuitions," he says, though certain minority populations here might be more attuned to this country's less democratic tendencies. "African-Americans are sometimes useful interlocutors about this because they might have different perspectives about, say, the rule of law in this country, or for how long America has been a democracy," Snyder explains. "White people will [tend to] say it's been a democracy since the beginning," he says, while it's likely that "black people will perfectly reasonably say no, it's been kind of a democracy since the 1960s." Whereas many Poles, Russians, Hungarians, Germans and other Europeans have some memory of authoritarian rule, most Americans don't.

But Snyder isn't like most Americans. His story starts off typically enough—he grew up in Ohio, played baseball and participated in Boy Scouts before going off to college at Brown University, where he studied European history and political science. He won a Marshall Scholarship and went on to earn his doctorate in Modern History at the University of Oxford. His plan had been to become a journalist or a diplomat, but he loved history and realized, with some help from his adviser, that he was better suited to become a historian.

Related: How the #Resistance is Tapping the Tea Party's Playbook

He arrived in England in 1991, soon after the opening of the Berlin Wall and just as revolutions were transforming Eastern Europe. He traveled, made friends and learned languages—he can speak and write in English, French, German, Polish and Ukrainian, and can read and understand Russian, Czech, Slovak, Belarusian, Yiddish and Spanish. He put his new language skills to use as he gained access to historical documents in those tongues. The early 1990s were "a time of unprecedented opening of archives. Nothing like this has ever happened before," he says. "I could study things that people just hadn't studied in 50 years."

He wrote his dissertation on the 19th-century social thinker Kazimierz Kelles-Krauz, and has published about a dozen books, most recently Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2010) and Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning (2015). These last two titles have been translated into dozens of languages, won him several accolades, as well as scathing criticism, and made multiple best-seller lists. He came to see his role as a historian of 20th-century Eastern Europe as a moral burden in addition to an intellectual one. He began to think that the atrocities in that region's recent history, including both Stalinist and Nazi terror, "were the most important subjects, not just in terms of explanation, but also sort of in terms of ethics," he says. "If one is going to be an East European historian, one should try to understand how these sorts of things take place."

He's learned that "democratic liberal regimes set up in the best of faith with good constitutions and all of that, can fail," he says. "Historically they usually do fail. And they don't always lead to something like Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union, but they generally do fail." And he knows something about what it might feel like when that process begins—how language changes, how the minutiae of daily life changes. "We don't tend to think those things are possible or we tend not to think they're possible in our own country," he says. "And of course we're wrong. They're possible here just as they're possible elsewhere."

Going Viral

The by-now-familiar story of how On Tyranny came to be—beginning on social media and ending up as a tangible object meant to be carried around, away from computer screens—is a demonstration of Snyder's lessons.

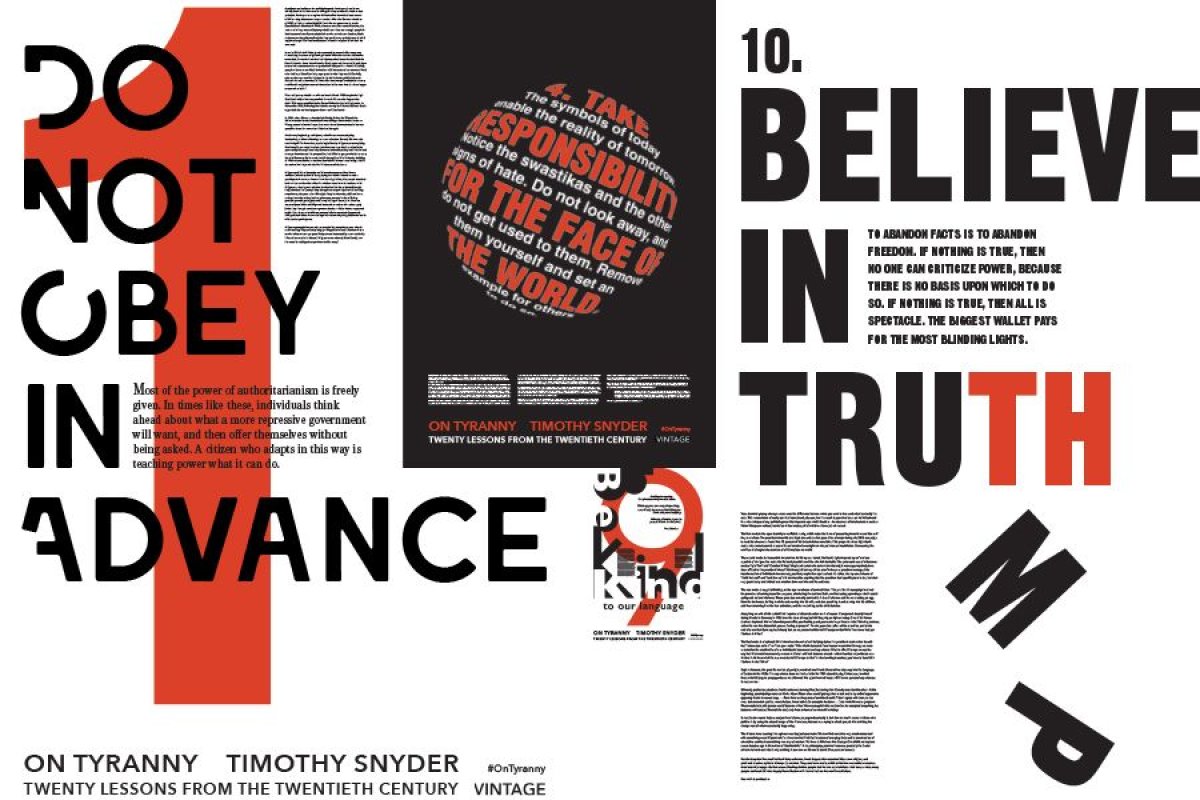

The list of insights he posted on Facebook on November 15 was concise and encouraged action: Do not obey in advance; defend an institution; recall professional ethics; when listening to politicians, distinguish certain words; be calm when the unthinkable arrives; be kind to our language; stand out; believe in truth; investigate; practice corporeal politics; make eye contact and small talk; take responsibility for the face of the world; hinder the one-party state; give regularly to good causes, if you can; establish a private life; learn from others in other countries; watch out for the paramilitaries; be reflective if you must be armed; be as courageous as you can; be a patriot.

The post—in which each lesson is followed by a few sentences of explanation—has been shared more than 17,000 times and viewed many more times than that. People also copied and pasted, tweeted and otherwise circulated the lessons. The Dallas Morning News picked up the list the following week and several other publications in the U.S. and abroad soon did the same. By Snyder's count, the list, in all its iterations, was seen by millions.

But Snyder wanted to codify his work and decided, with the help of his publisher, to flesh out each lesson and publish them all in a paperback. "Since my whole point is that history can help us I should be able to do that." And so he did, citing examples from Nazi Germany, Communist Czechoslovakia and elsewhere. The manuscript was submitted by Christmas and he was reviewing proofs by January. It wasn't out the day of Trump's inauguration as he'd hoped, but just over a month later, on February 28, the tiny paperback manual hit shelves and pockets.

By writing his lessons so soon after the election, "I was taking a certain chance that he would continue to behave way he had," he adds, speaking as he writes in the book, without using Trump's name to underscore that the problems are structural rather than personal, and to establish a common ground of fundamental threats to American democracy. The book, Snyder emphasizes, is meant for everybody—liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, supporters of Hillary Clinton and Trump alike. "I am trying to start from the Constitution, checks and balances, the rule of law, the elections. Things that we care about. I'm trying to make a case that those things are not only precious but fragile."

On Tyranny climbed at one point to the No. 1 spot on Amazon's best-seller list for books and currently stands at No. 3 on the New York Times paperback nonfiction list, right behind The Zookeeper's Wife and Hidden Figures. Snyder's U.K. publisher created a series of posters that together contain the entire text of the book and posted them on a street in London.

This is not a book that's meant to be read once and placed back on the shelf. Snyder says it can continue to serve as a resource to refer back to "at the end of the day when something shocking has happened."

Do Something

Snyder would much rather be living in an America that didn't require him to step away from reading and writing history books to write those 20 lessons. He has also spent time writing other essays in the same vein, including "Him: His election that November came as a surprise…" for Slate, a nameless description of Adolf Hitler's rise to power, the first half of which is eerily transposable to a more recent November election. The New York Review of Books published " The Reichstag Warning," delving in detail into lesson 18, which warns that "when the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power," as Snyder writes in On Tyranny. It's "the oldest trick in the Hitlerian book. Do not fall for it."

The banner of his Twitter profile, where the historian has more than 24,000 followers and growing, now reads, "Don't be a bystander." This is a "moment which will determine not only the kind of life I have but the kind of life my children have and their children have," he says. He'll continue on this path "for as long as I think it will make a difference."

Snyder has already observed some promising signs since November 8, including vociferous protests, the mobilization of lawyers in the face of Trump's executive orders on immigration and states filing lawsuits to block some of the administration's actions. But "what's discouraging is the idea of Islamic terrorism is seeping downward" and the sense that the distinction between security and religion is breaking down. What's most disappointing, he says, is the normalization.

Still, he remains optimistic. "Everybody has something that they can do," he says. "It sounds kind of dopey and Hollywood but if everybody does something then I think this is going to turn out OK."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.