Scientists have discovered over 50 new genes relating to intelligence—a finding that gives us a far better insight into the "genetic architecture of intelligence" and how this relates to IQ.

While the exact percentage is widely debated, scientists generally agree that a large proportion of intelligence is inherited—and therefore based on genetic factors. But intelligence is not a straightforward trait influenced by just a few genes. Rather, there are hundreds of genes that make up a complex web, the vast majority of which research has yet to identify. Environmental factors can influence intelligence too, including education and upbringing.

A team of scientists has now uncovered over 50 genes relating to intelligence using a sample of almost 80,000 people. Their large-scale meta-analysis took into account several different measures of intelligence, coupled with the participants' genetic data.

Read more: How scientists in Britain are deciding the future of humanity

Two types of genetic analysis revealed different genes linked to intelligence. The first, known as a genome-wide association study, revealed 22 genes, 11 of which were completely new. In the other approach, genome-wide gene association analysis, the team found a further 29 new intelligence genes.

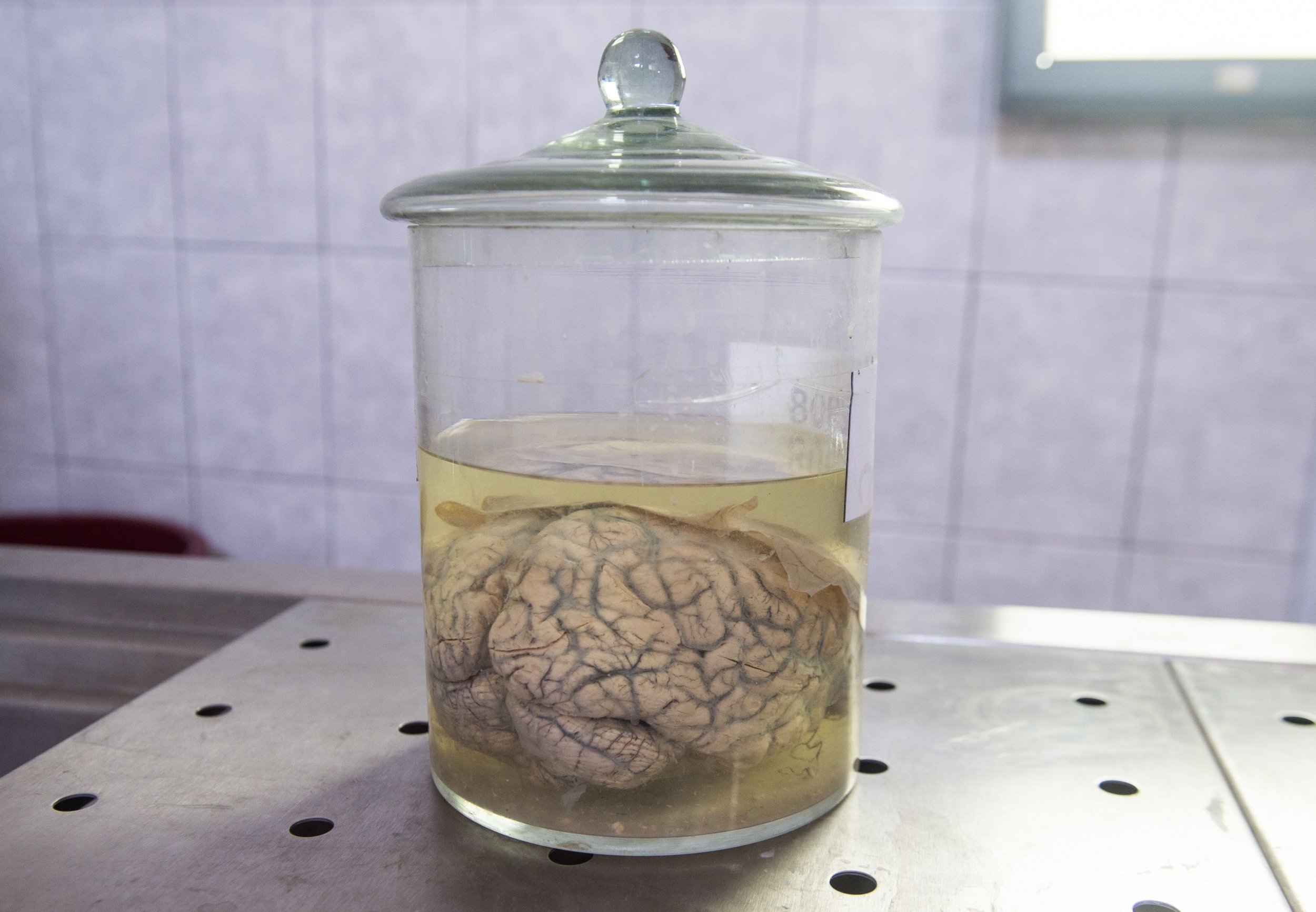

Most of these genes were found in brain tissue: "Pathway analysis indicates the involvement of genes regulating cell development," the scientists wrote in the journal Nature Genetics.

Corresponding author Danielle Posthuma, from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands, tells Newsweek she was not expecting to find as many genes as they did: "I've run a lot of genome studies and a lot of the time you don't find a lot of genes, even though the traits you are investigating are highly heritable. And it's only if you have a really large sample size that you start to find things."

While the number of genes identified was "happily surprising," Postuma says there are hundreds more they need to find before they have a complete picture of the genetic influence of intelligence. Following the study, the team used the findings to try to predict intelligence in another, independent sample. "The prediction estimate was only good for five percent of the variants in that sample. That's a huge increase—double what we could do before—but still it's only five percent."

She says these genes cannot be used to genetically engineer more intelligent animals—adding that attempting to do this could have unknown consequences.

"For these 52 genes we won't be able to increase intelligence," she says. "The heritability of IQ is 80 percent, so it's still a long road before we find all the genes. And even if we find them there might still be environmental interactions, or gene interactions that we haven't really investigated but that might be important. So I wonder if we'll ever be able to do this in mice or humans.

"For any trait that's only influenced by one or two genes, it's easy because then you just repair that gene—if it's a disorder, for example. But for intelligence there are so many small effects and they don't only influence IQ, but also other traits, so if you start messing around with them you might end up with an intelligent animal, but there might be all sorts of other problems. It's something I would never want to do or something anyone should try to do."

Next, the team hopes to identify more genes relating to intelligence as well as carrying out experiments to look more closely at several of the genes found. Posthuma says, "If we start messing with these genes, what happens on the cellular level? We hope to find the biological mechanisms involved [in these genes]."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.