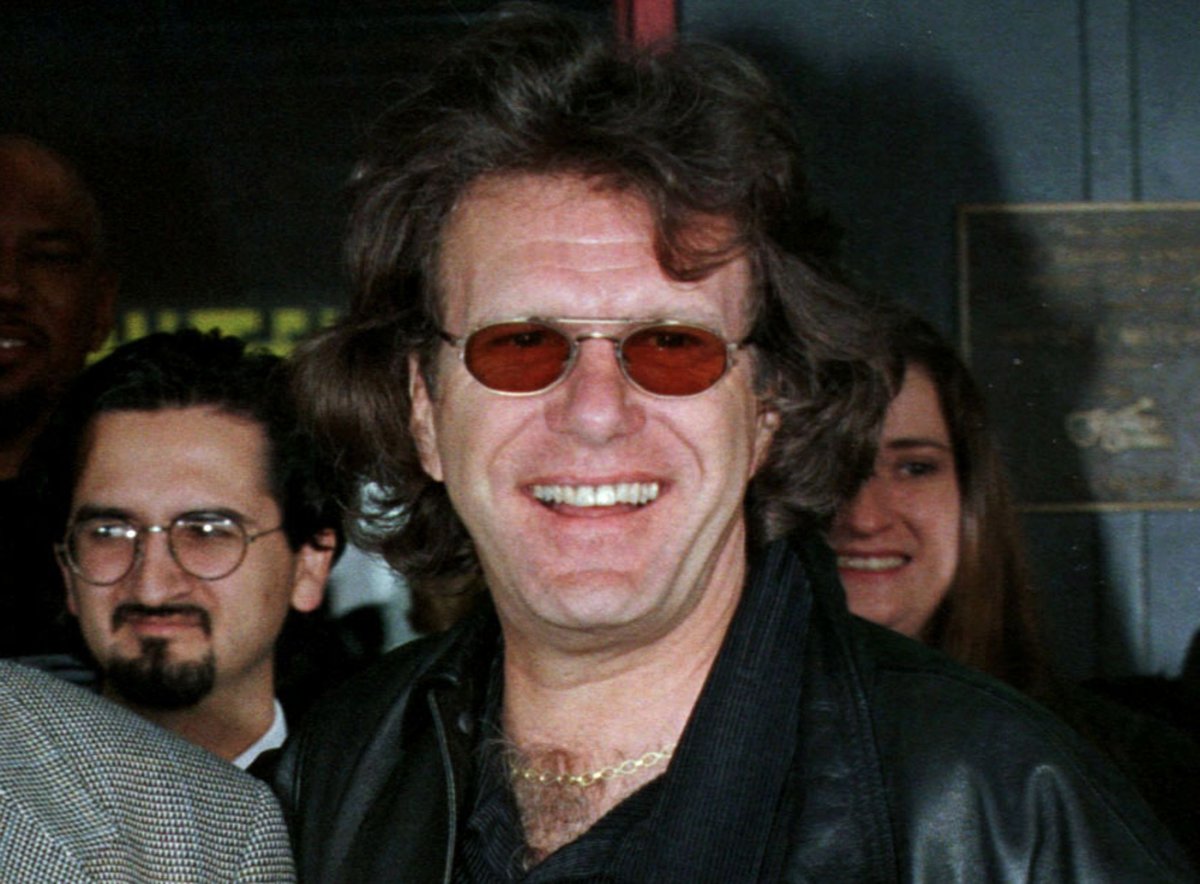

Earlier this year, two progressive-rock legends were on the verge of reuniting. After planning to play in Japan with his group in May, keyboardist Keith Emerson intended to perform with drummer Carl Palmer and his group, ELP Legacy. It would be their first time playing together since 2010.

The show never happened. Emerson, who revolutionized the keyboard's role in rock with his magnificent, classical-inspired compositions and astounding instrumentation for Emerson, Lake and Palmer, took his life on March 11 in Santa Monica, California. He was 71.

After Emerson's death, Carl Palmer's ELP Legacy performed a concert in Miami to honor the keyboardist. The show also featured former Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett and Vanilla Fudge keyboardist/vocalist Mark Stein, as well as dancers from the Center for Contemporary Dance. A DVD of the concert, Picture at an Exhibition—A Tribute to Keith Emerson, is due out soon.

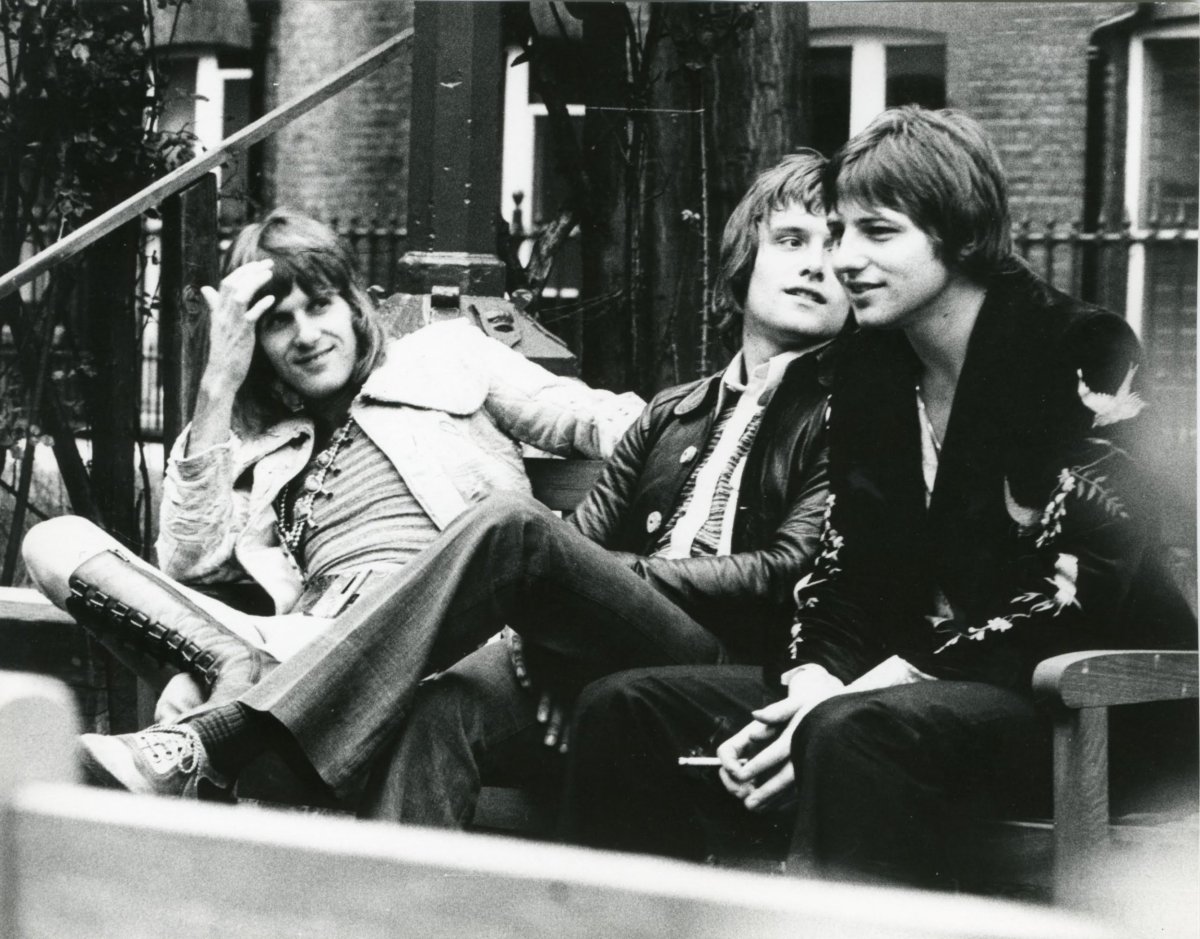

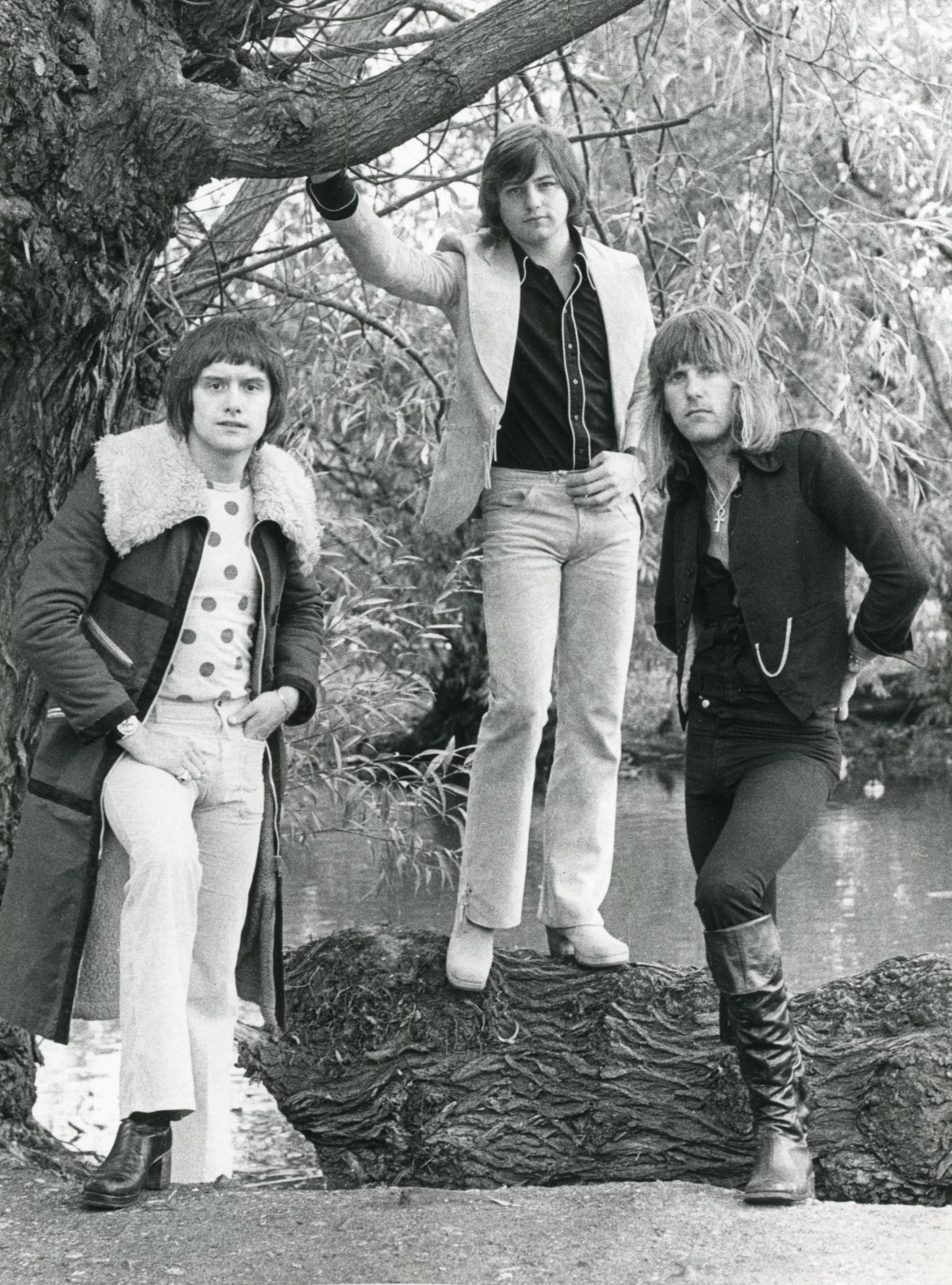

Emerson formed ELP with singer/bassist/guitarist Greg Lake in 1970. They came together in London after having played in two acclaimed British progressive-rock bands: Lake was in King Crimson and Emerson in the Nice. Palmer, formerly of Atomic Rooster and the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, became the third member, his extraordinary drumming serving as the ultimate complement to Emerson's mammoth keyboards. It was a trio that turned rock into a whole new animal, one in which European influences, rather than blues and other American musical styles, were at the forefront.

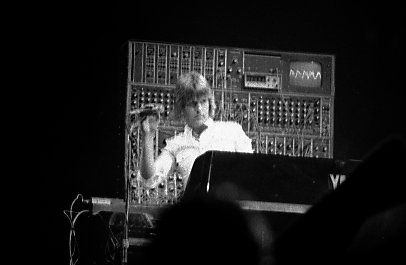

Finally, there was a rock group whose main instrument wasn't the electric guitar. Directly at the core of ELP's unique sonics were Emerson's ingenious use of Hammond organs, Moog synthesizers, pianos and clavinets. His wizardry yielded ambitious, difficult to categorize compositions such as "Tarkus" and "Karn Evil 9"; adaptations such as Modest Mussorgsky's "Pictures at an Exhibition"; and shorter gems like the honky-tonk-infused "Jeremy Bender." Onstage, Emerson became known not only for his keyboard virtuosity but for his signature showmanship, as he worked his huge arsenal of instruments like an otherworldly prog-rock pirate. He would rise into the air as he and his piano would do somersaults, and stab daggers into his Hammond. Considering Emerson's immense musicianship and daring stage presence, it's no wonder that many described him as "the Jimi Hendrix of keyboards."

Newsweek spoke with Lake and Palmer about Emerson's enduring legacy and the groundbreaking trio that he co-founded.

Greg, when you decided to form ELP with Keith, what were some of the musical ideas you each had for the band?

Lake: I think the fundamental thing was that Keith Emerson and myself had this shared belief that too much rock 'n' roll music had been based on the blues, Motown, gospel, country and western—all American-influenced. I hasten to add: Nothing wrong with that; I love American music. At the time, Keith and I agreed that there needed to be something different taking place. And so we decided, really, to use European influences rather than American influences, in our music. And I think that was a common bonding factor that we had, even before Carl joined the band.

What was special about having the keyboards as the main lead instrument?

Lake: There are pros, and cons. Of course, immediately, you opened yourself up to orchestration; you're able to replicate orchestral sounds. That we did incorporate strings or French horns, or anything we wanted, into our sound, was a huge advantage. The disadvantages, particularly as a singer, is that a keyboard is capable of endless sustain [laughs], whereas a guitar plays and stops, so the vocalist, usually, gets a chance to have breaks in the sounds. Whereas when you've got keyboards going, you're fighting pretty much all the way down the line.

Did Keith ever mention to you what he felt were his favorite pieces to perform?

Palmer: I think for Keith, to be honest with you, he would as happy playing "Abaddon's Bolero" [from 1972's Trilogy] or "Bitches Crystal" [from 1971's Tarkus] or playing "Jeremy Bender" [Tarkus]. He wasn't a favorites-type of guy really. He liked a lot of music, he was excessive with music. He liked it all. I never heard him say, "Oh, this is my favorite." I don't think he limited himself down to that kind of area.

Carl, before joining Emerson, Lake and Palmer, you were the drummer of Atomic Rooster, which you formed with organist Vincent Crane. What was going through your mind when you were asked to join ELP?

Palmer: Well, to be honest with you, joining Keith and Greg, it wasn't at first at the top of my list. And after that, I did decide to join them, and the group Atomic Rooster suddenly ended up being No. 1 in the English charts, with the track called "Tomorrow Night," which I previously recorded with them and they had to rerecord it with their new drummer. So I thought I had made a terrible mistake, to be honest with you. It was quite unsettling, and I wasn't sort of, like, totally convinced I did the right thing. Obviously, playing with the two of them was superb, and I enjoyed every minute of that, and I could see that there was a certain amount of success which will come our way.

How big it was going to be, obviously I didn't have a crystal ball then, and I don't have one now, so it's very difficult to say. But I think because we were quintessentially sort of English in what we did, by the time it moved to America it was obviously something that the American rock audiences wanted to see, because it was keyboard-driven, it wasn't guitar-driven. The guy [Lake] didn't sing with a bluesy voice, he sang with a choirboy church-like voice, and so we played classic adaptations, not rock, not really out and out rock 'n' roll, not out and out blues or jazz. So it was really a piece of Europe going to America and performing, and that's what we were. When the pictures started to form, I started to see what was going on. I realized that if we had a chance in America, then we would do very well. We were already doing remarkably well in Europe, Germany, Italy, France, England, so it was just a case of, Does it transfer across the pond? And it did.

How do you feel your drumming and musical approaches evolved while you were in ELP?

Palmer: We were classically sort of directed. I was very, very keen on classical music. So the actual musical structure of ELP was very much the way I thought we should go—playing adaptations, whether it be Mussorgsky, whether it be Bartók or Prokofiev. I come from a long background [in classical music]. My grandfather was a professor of music at the Royal Academy of Arts. I studied at the Guildhall [School of Music and Drama] and at the academy with James Blades and Gilbert Webster, so I was into classical percussion, and I was into learning as much as I possibly could about the percussion instruments.

Basically, I'm a rock drummer. I specialize in playing rock drums; that's what I am. But, you know, knowledge is power, so I just needed to gain as much information as I could about my instrument, and I did. And obviously it was easy to implement that in the structure of ELP, because of the musical direction we were going.

Keith and I had very, very similar ideas. When we went into our jazz collections of records, vinyl in those days, I noticed we had very, very similar collections. His first jazz album was my first jazz album: Time Out by Dave Brubeck. So there was a strong connection musically. Even though he was five years older than me, we kind of hit it off on many levels very quickly. I was ready to go any way we wanted to go, but the classical road suited me and does still today, because the training and education that I had managed to pick up before and while I was in ELP—I still attended the Guildhall for a little while in ELP the first couple of years. So I kind of carried on, right up until I was about 25, from an educational point of view.

Similar to Greg's vocals and Keith's keyboard, your drumming was a powerful signature element of ELP. With your instrumentation, rock drumming entered a whole new realm. What were some of your initial strategies when it came to drumming?

Palmer: We decided that because I had a technique—and just because it was there didn't mean we had to use it. The way the group sounded bigger was if I were to reinforce the whole thing rather than just keeping time, which is quite a mundane thing to do. If you could embellish the music and make it sound bigger and fatter and more exciting, and more direct, we figured that we could take the drums that way. And when we needed to rock solid, then for those eight bars, I'd be rock solid, but then get back into playing as many things with Keith or against what Keith was playing, to counterpoint it. We didn't think of the drums as just being there to keep time. We considered it like another lead instrument in a way.

Your drums' lead role certainly showed itself early on—especially during "Tank" from the debut album.|

Palmer: "Tank" was the very first piece that I actually wrote with Keith. I had a couple of musical ideas, which I played to him. And I had this rhythm and said that we could have these starts and stops. And I asked him, "What do you think?" We kind of just kicked it around for a couple of hours that day, and the next day, we got it down and just played it. I think it probably happened the second take. It was one of those kind of very natural pieces that just sort of fell under our hands, and we decided, "Oh, we'll put a drum solo in that."

A lot of those things were quite organic and they developed very quickly, which is always the best way. If we have to sit around for days and days, it's usually because something is wrong with it. But "Tank" was extremely spontaneous, and I like it a lot. I'm very, very happy with it, and I continued to play it live with my own band. It goes down incredibly well. People still remember it.

You mentioned ELP's interest in performing classical adaptations. One of ELP's greatest adaptations happens to be "Jerusalem," which opens 1973's Brain Salad Surgery.

Palmer: "Jerusalem" has a great story attached to it. It was recorded here in the U.K., and we had to present it to the BBC. The BBC had a panel at the time, and they would veto what would be played on the radio and what could be shown on television, so for us to get the single released, it would have to go in front of this BBC panel, which was about four or five people. If they said no, then you couldn't release it as a single, and it wouldn't be played on any radio stations throughout the British Isles. And obviously if they said that, it meant you couldn't play it on the television, though we would never have gone on to the television anyway.

So "Jerusalem" was recorded by us, and it was banned immediately by the BBC. We thought it was an unbelievable piece of music. It actually summed up prog rock, British prog rock, in that moment in time. It had everything. It was so grand, it was so English, and it was absolutely perfect for the voice. And it just painted a thousand pictures when you played it. So it was definitely the piece that meant an awful lot. We released it in defiance because that was truly ELP form, and the fans loved it, and we played it onstage quite a few times. I'm still playing it today actually. I'll be playing it the rest of this year because it's part of the program I discussed with Keith. And I did record it in Florida for the tribute DVD for him, but I actually used a choir from Florida to sing along with that one. So I'm very pleased we've got that for him.

Lake: "Jerusalem" is a British national song. It's sung at churches a lot. And it's something, as a kid, you were always aware of. There's a few beautiful lines: "Bring me my bow of burning gold!/Bring me my arrows of desire!" It's a wonderfully uplifting piece. And so it was a wonderful thing.

It really showed how ELP was able to reinterpret music with its unique approach.

Lake: I think that was one of the qualities of ELP. We were able to sound much bigger than the number of people in the band. I'll tell you what: When you look at other three-piece bands, the good ones, you will see a similar thing: Jimi Hendrix [with the Experience and the Band of Gypsys], Cream, Police. They all sound somehow bigger than three people.

Greg, you mentioned Jimi Hendrix's work with trios. One can also compare ELP to Hendrix because of the role Hendrix and Emerson each played in their respective groups. Like Hendrix, Keith was a virtuoso whose keyboard was often the pivotal instrument. And in certain ways, Keith revolutionized keyboards in rock much the same way Hendrix did with the guitar.

Lake: I think that was true. I think he was unique, with his whole approach to music. You know, well, it sort of verged on slight insanity. He pushed the limits of believability. He was absolutely original. Yeah, I think he defined modern keyboard playing. There's no one else I can personally think of that's left a stamp like that on keyboard music of the 20th century. Gershwin is another.

What was challenging about presenting ELP's lengthy, elaborate pieces, like "Tarkus" and "Karn Evil 9," in concert?

Lake: It presented a huge spectrum of challenges, from the visual to the sonic. Getting the music across. You know? You have to work hard as a three-piece. You haven't got tons of dancing girls flying around. You have to do everything yourself. To raise an audience to a frenzy is quite a challenge.

Besides the sound of the band, there was always plenty of showmanship during an ELP gig.

Lake: With our production we were never gratuitous, we never did just production for the look of it. We always attached our production directly to the music. So when we wanted to create an enormous amount of excitement, Keith would stand on the organ and ride it across the stage, and he would stab daggers into the keyboard, that was related to "Rondo" [a song written by Brubeck that was recorded by the Nice and also performed live by ELP]. That was the peak of the show, so it was a visual and audio moment. Keith would have both hands and both feet on the go. Absolutely everything all the time.

Flying pianos, and pianos on top of Keith, were part of the ELP live show.

Lake: Yeah, that was an unbelievable thing [Emerson playing the keyboard while it was on top of him]. He hurt himself a couple of times doing it. And the piano did fly up in the air, it did fly around and around, and he was sittin' on it! [Laughs.]

You don't have too many people doing those kind of stunts these days in rock.

Lake: Not if they've got any sense. If they like their front teeth, they'll avoid that.

When you look back on the many times you worked in the studio with Keith, any moments that especially come to mind?

Lake: For a start, the song "Lucky Man" [from ELP's eponymous debut album] was completely unintentional. It only came about because we had run out of material on the first album. So that happened by accident. We had come to the end of the studio time, and when we counted up—in those days, of course, the records were vinyl, and you were supposed to have, and I can't remember now, but it was either 19 or 21 minutes per side—and we were short of a song. Because we had been ushered into the studio so quickly, we hadn't written enough material.

And so, there was this moment where the engineer, Eddy Offord, said, "Has anybody got another song?" And we were all blank faces. I said, "If there's nothing else, I've got this folk song that I wrote while I was a kid." And they said, "Pffff." It was a simple little thing. I played it to everybody, and no one liked it. And so I said, "We haven't got anything else; let's just do this as a sort of, at least as a filler." Keith couldn't even begin to relate to it. And he went off down to a pub for a drink, and Carl Palmer and I cut the record together. It was just the two of us. And it sounded dreadful. It was just acoustic [guitar] and drums. It sounded really clattery.

Then I put a bass guitar on it, and it sounded a bit more complete. Then I started singing, laying on harmonies, putting on electric guitar parts. Keith comes back from the pub, absolutely astounded. "What's happened?" And then he said, "Well, I'd better play on it somewhere." I said, "Well, the thing is, I've already done the guitar solo." He said, "Ok, I'll just put something over the end." That very day, we'd had the very first Moog synthesizer [ELP would use] delivered to the studio. So Keith said, "Maybe I could get a noise out of this." So he was experimenting, we recorded the experiment. He was doing practice run-throughs. And I always press Record just in case you capture something special. And so it was.

At the end of this tape is this practice run-through, I looked at Eddy Offord, and I said, "Am I hearing right? Did that sound good or not?" And Eddie said, "I think it did, just play it back." We played it back. When we said to Keith, "It's a great solo, come and listen," he said, "No, no, no, no." He said, "I was just fiddling around. I could do much better than that." So in the end, after a long argy-bargy, he came in and listened. And that is the solo on the end of the actual record.

It's interesting that the first album ended with that Moog solo. In a way, it was like a sign of things to come, because on Tarkus, Keith's keyboard and synthesizer work became absolutely astonishing.

Lake: It steams in on Tarkus. And you're quite right. It set up the next record really. And Tarkus was made as it went along. We wrote the album as we recorded it.

Palmer: Tarkus was one of the first concept albums, though the concept is a little bit weak. But the actual music and the lyrics are incredibly strong, and it was a blueprint for many, many groups to follow. That particular piece of music [the title piece] was just over 20 minutes long. We couldn't actually play it all completely without making mistakes, 20 minutes is a long time, so we had to get edit points. The original recording of Tarkus—don't forget, it was analog then, so it was straight to tape—actually had 17 edits in it, so we would mark out how far we could go before we needed to regroup and start again. And we'd mark it out in the music, and we'd record up to that point, and then record the next bit, and the next bit. And there were great moments when it was all happening and the creativity was there. We could play it, but we couldn't play it perfect—but we could play it perfect in sections. That was a big moment in time.

There are moments all the way around that really stick out. The writing, the actual performance, the recording, the lyrics: I'm extremely proud of it. Brain Salad Surgery was another great time. It was when the group was probably at its pinnacle of creative powers, and that album probably sums it all up, and not just as far as creativity but technology: An electronic drum solo was recorded on a piece called "Toccata"; people thought it was from the keyboards but it was all being triggered from the drums. I'd had these drum synthesizers made just for me; they weren't in general production. We decided to use them on that recording, so that was very forward-looking at the time.

ELP's use of studio technology began to blossom while recording Trilogy. How did the band grow while making that album?

Palmer: Trilogy was the first album we decided to overdub as much as we possibly could to enhance the music. Our attitude prior to that really was, "Let's make sure we could play it as a three-piece band onstage and sound really big; let's not record more than what we could play." So as a matter of fact, that was a great way to look at things; it's also going to hold you back, because it means if there are overdubs that you'd like to do, then unless you bring another keyboard player along, because MIDI [Musical Instrument Digital Interface] wasn't invented then, you're not going to be able to play the stuff.

So Trilogy, which is a great album, was played the least onstage because it had so many overdubs all over it. And I said MIDI wasn't invented, so Keith couldn't trigger two or three keyboards at the same time. That album didn't get the airplay that it possibly should have. But that was us really trying to stretch it out. With technology today, we could produce that album exactly onstage.

Lake: When we recorded that album [Trilogy], the technology was blossoming, and it coincided with us making this European-based, classically influenced music, which got tagged with the term progressive, which I hate. I don't like progressive, it sounded elitist and smart-ass. That wasn't what we were trying to do. We were just trying to be different, really. Another thing we got tagged with was the word supergroup, which we didn't need either. We hated it. It was just because Keith and I had come from quite well-known bands. It made us sound like sons of rich and famous fathers, you know? Which we weren't. We'd paid our dues just like every other rock 'n' roller.

During ELP's 1977-78 tour, the band performed with a large orchestra for some concerts.

Lake: It was a different ELP; it was ELP viewed through the prism of an orchestra, as opposed to the raw three-piece band. And in fact, what we learned in the end, strangely enough, was that the public preferred the three-piece band. They just did. That's what they grew up with, that's what they loved, that's what they knew, and this sort of vision was something that, yeah, it was very impressive, it couldn't help but be, but it wasn't ELP. It was ELP as members of an orchestra. And in some way it diffused the power of that band.

Were there primary challenges of performing, and ultimately recording, with the orchestra?

Palmer: It was a challenge that was really just to do with the technical side. We did have a problem with recording the live album from Olympic Stadium [In Concert, recorded in Montreal]. We had a 24-channel desk for the orchestra, a 24-channel for the group, and for some unknown reason, the 24-channel orchestra desk had gotten damaged, about 24 minutes before we were about to go on, and we couldn't delay the show. So we had to reroute the orchestra desk and put them onto four channels, two stereo pairs, onto the group's 24-channel desk. That was the only way we could record it that night.

That was one hell of a challenge. Rehearsing with the orchestra and all that kind of stuff, that really wasn't very difficult at all, it was just time-consuming. The recording didn't turn out as nice or as good as what it should have been because we didn't have as many tracks for the orchestra as we would have liked. And the orchestra itself didn't really enhance the group Emerson, Lake and Palmer because we'd been away for too long.

In hindsight, it probably would have been better if we'd come back and played as a three-piece, and then three weeks down the line brought the orchestra in to show some kind of development. But we were kind of gung-ho, and we came straight out with the orchestra and ready to blast. We only lasted really three weeks out of the six weeks with the orchestra because of the actual finances we needed to run with all the people. We discovered that it would be better to lay them off, to cut down on our expenses and finish the tour as a trio. If we didn't sell every seat in the place, we were losing far too much money.

What were some of the ELP performances that most stick in your mind?

Palmer: I think California Jam in '74. Thousands of people got in for free because they broke down fences. Black Oak Arkansas and Black Sabbath were also on that. We were headlining with Deep Purple. That was quite frightening at the time. It looked a little bit sort of dangerous to me [laughs]—that was a lot of people to have in front of you. I would also say the Montreal Olympic Stadium with the orchestra. That was where we made the first "Fanfare for the Common Man" video, where we're walking in the snow across the arena. And that summer, we played the concert there.

And I suppose if you go back even further, the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970. We had played in England on the coast in the south, in the Portsmouth Guildhall. And three days later, we get the phone call: "Would you like to play on the Isle of Wight?" And we played for literally 47 minutes, we were a last-minute call. We flew in with a helicopter, and we flew out directly after the set because the roads were so congested; it was so badly organized. And people really didn't know what to expect. I remember going home that night thinking, Well, this is interesting, and in the morning when I woke up and read the papers, it was like we went to the Isle of Wight completely sort of unknown but left as an international rock band. So that's incredibly memorable.

While some of ELP's best music comes in the form of longer, technically ambitious pieces, the band was also known for a number of shorter songs, including folky tunes featuring your acoustic guitar work. What was it like presenting both sides of the band?

Lake: One quality, I think, that made us successful was our ability to go from the extreme, aggressive to the very beautiful and tranquil. It was that dynamic range—one minute we'd be playing "Tarkus" and the next, "Still...You Turn Me On." This was a journey. So people went up and down, up and down. And by the end of the concert, they pretty much had been there. Different people like different things, thank God. Somebody might like "Lucky Man" while "Tarkus" might not be their thing. The idea of doing it all was really to bring people in. And you often found people who would get into the band with a simple song like "From the Beginning" or "Lucky Man."

Keith's keyboards often took center stage in ELP's music. But Greg, your guitar—both your electric on, say, "Karn Evil 9," and your acoustic work was also a key component. And the guitar often seemed to arrive at just right the moments.

Lake: I started playing when I was 12 years old. And for many years, I was a guitar player. And so, for me, there was always a special joy in being able to play the guitar with the band. Problem was, as soon as I picked up the guitar, there was no bass player. So we had to figure that out pretty carefully. One of the other reasons we wanted to use the guitar is that it added to the palette, to the dynamics of the band.

To this day, Emerson, Lake and Palmer are still not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. What are your thoughts on the fact that ELP, as well as other bands that define so-called progressive rock, like Yes, haven't been inducted?

Lake: Millions bought those records, and that's not represented. So I think, really, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is being a little bit parochial, they're being a bit small-minded. And they're defining these barriers. It's as if they don't like it, so why should anyone else?

With all the humility I can muster, I would also say that ELP was quite influential. A lot of bands grew on that. So it wasn't as though we were just a pop band that had a few hits. To this day, I can name people who would happily admit it. Go talk to Tran-Siberian Orchestra, for example; Paul O'Neill would tell you. If there was no ELP, there would be no Tran-Siberian. I'll tell you what, though: By the time we do get recognized, it will unfortunately be too late for Keith. He devoted his life to music, and not to be recognized like that, hmm. Mean-spirited.

Greg, do you foresee performing any of the ELP material live someday?

Lake: Totally not. Funny enough, I did a tour a few years back with Ringo [Starr], and he wouldn't play Beatles songs. And I said, "Why? And he said, "It's not the Beatles. It wouldn't be the original thing." I think people deserve the original thing. And thank God there are records where you can hear the original artist.

What do you have planned these days, Carl?

Palmer: To be honest with you, there's the DVD, which will be out very, very soon. It's all mixed, and all the artwork is done. It has Steve Hackett playing on a couple of pieces. It has Mark Stein on it, from Vanilla Fudge, singing on "Karn Evil 9" and "Knife Edge." I've also done painting; if you go to Carlpalmerart.com, there's a 60-by-60 painting, a rather big painting I've done in dedication of Keith. It's called Welcome Back My Friend to the Show That Never Ends. I'm also trying to sort something out here in the U.K., but it seems to be a bit difficult to organize a concert at the moment. It's going to be next year. That's where we are, really.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.