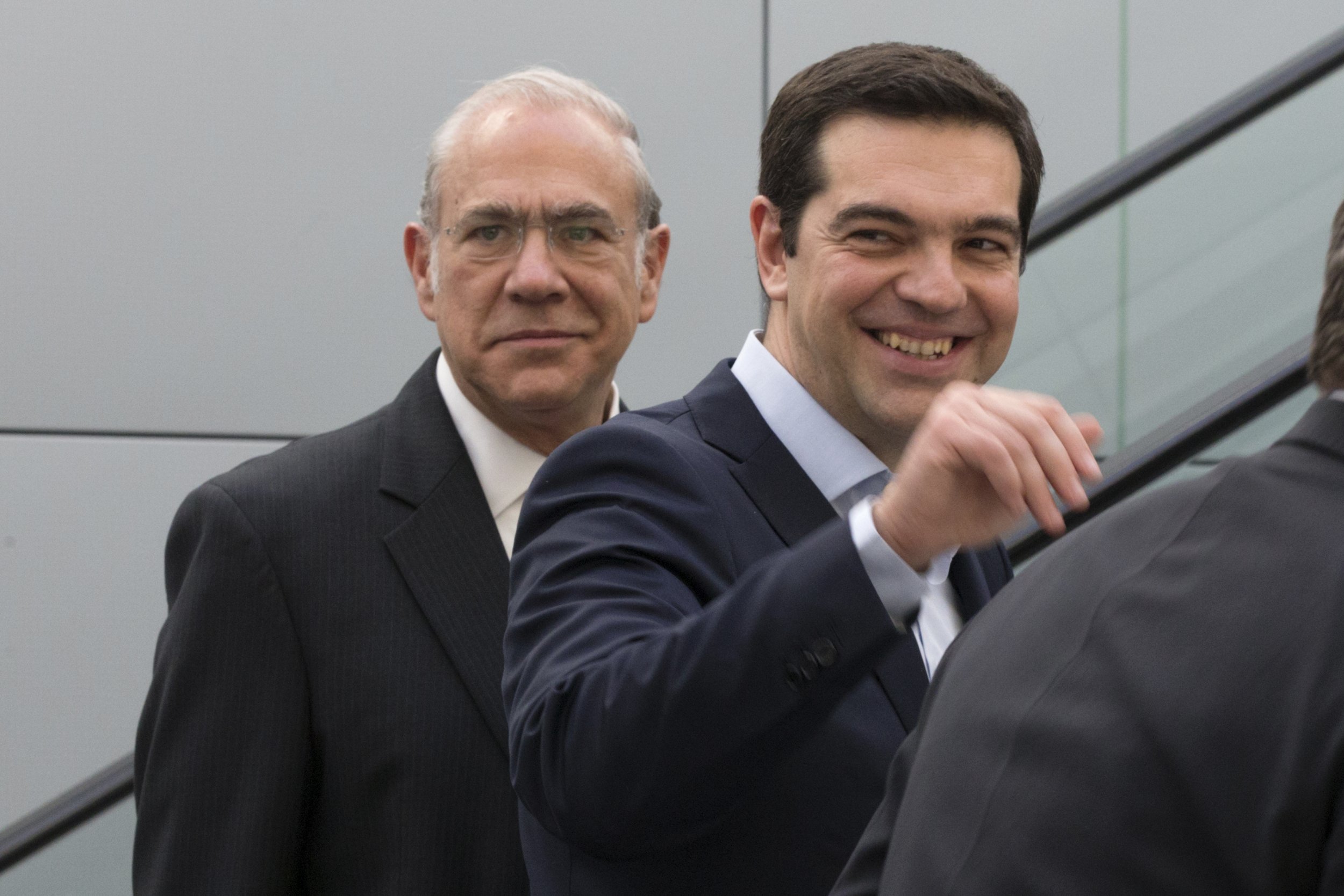

Mexican economist Angel Gurría currently serves as secretary-general for the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an international economic group dedicated to improving economic and social wellbeing worldwide.

But Gurria is best known, first as secretary of foreign affairs and, later, as secretary of finance, for restructuring his country's then-burgeoning debt at the height of a series of financial panics that plagued the Mexican economy throughout the 1990s.

Gurria sat down in his Paris office just before leaving for the World Economic Forum to talk to Newsweek's Middle East Editor Janine di Giovanni about post-war economies, corruption and lessons learnt from the Peso.

JD: You came of age during the Latin American debt crisis and so you're someone who can really link the lessons you learned then to what's happening now in Europe. What came out of that for you?

To be perfectly honest, by the time the debt crisis came around I was of age. We actually borrowed a very great amount in the second half of '81—34 years ago. During that time, we borrowed about 18 billion net. The debt became shorter and shorter term.

What did that feel like? The responsibility of that much debt…

It was troublesome. The whole banking sector in Mexico was literally bankrupt. For whatever reason, instead of intervening in the sector or supporting the banks, the government expropriated them. We went through the very laborious period of selling the failing banks to the wealthy people of Mexico.

You sold the banks abroad as well. Not just to Mexicans, but to people in places like Britain.

We sold them abroad but with carefully established limits. Effectively, we ended up with a foreign owned banking system that's still the same way today to some extent. But the difference now is that we have more competition. It doesn't really matter who owns things so long there is enough competition, which means lower pricing, better quality goods, more variety and an economy where the consumers are the big winners.

So everyone believed in protecting the infant industries?

Or even just the ownership, though some of the industries were no longer infant.

But we have a lot of experience on what not to do, which has served us well. We've become somewhat of a model. You see, during the financial crisis, private banks were selling to each other at a discount but were expecting us to pay out 100 cents. So we said, "Okay, if you're willing to buy and sell your part of our debt at 70 or 60 cents on the dollar, why don't you give us the benefit of 70 or 60 cents on the dollar. We'll give you a new bond—and enhanced bond, maybe even guarantee some of it somehow." And eventually they did. Eventually the bankers understood that if they did not give us a discount, we were going to have a problem with the debt at large. Then the benefit wouldn't be worth 60 cents but 20 or 15.

As a young Latin American economist, what were your influences? Were you influenced more by what happened early in Latin America with the Chicago boys and Milton Freidman? Or were you more drawn to poverty reduction like Hernando de Soto Polar?

I would say neither. I was very pragmatic. I was an economist out of the National University of Mexico, where you lived the realities of Mexico all the time. In a country like Mexico you can't forget about poverty—about how half of the population lives in poverty, and how half of that half live in extreme poverty. Poverty is something you grow up with in Mexico, so you can't be chemically pure and ideological.

I work in conflict zones and was wondering how economists rebuild economies in areas devastated by past conflict?

It depends on the endowment as well as how the country was left after the conflict. It's also important to note that post-conflict yields a lot of new but equally trying problems. Take for example, Iraq. We didn't manage the transition from war to peace well enough to create a unified country, instead opening all sorts of cracks in its social facade. So now you have problems such as ISIS.

Are there specific economic tools? Are there specific economic tools you could use in a country like Iraq, or Syria, once the peace treaties have all been signed?

Yes. First of all, if you're Iraq and you have oil, regardless of the price today, eventually you could end up producing millions of barrels of oil a day and use them as economic leverage. But for any post-conflict nation, the questions are whether you can move into manufacturing—including into what I'd call "value added manufacturing"—as well as into the services industry (i.e. tourism), whether you can bring everyone on board, and whether you can attract foreign investment.

Syria is different. Its conflicts have been very destructive. They've lost major cities to carpet bombings. There's no activity; the people have fled. Chemical weapons were used against its citizens. And on top of that, there are the conflicts with other nations (i.e. Russia). How can you undo the effects of all of that? Well, it will require massive flows of aid before you can get to the part of reconstituting the economic system.

But doesn't aid also pose its own problem because of dependency?

Yes, but you have no choice. The questions are how to use aid, what to use aid for, and how to make aid a detriment catalyzer of other flows. If you only have aid, then you become dependent. But Syria is too big a country to sustain only with aid.

In many of the Arab countries, there is this problem of crony corruption—crony capitalism. How do you get to the core of and ultimately eradicate corruption?

Corruption is not a monopoly of the Arabs. It is a very, very serious curse. It is something we should stamp out because, regardless of the ethical and moral implications, it produces serious misallocations of resources, so just the economics of corruption is bad. Corrupt officials are causing the distortion of many millions if not billions of dollars on the wrong projects, the wrong technologies, the wrong locations and the wrong suppliers. And then their countries are stuck with the consequences of a series of bad decisions for a generation.

How do you root out corruption?

Well, there are a number of ways. First of all, you have to pay your civil servants a decent wage. Sixty per cent of the acts we've identified occur in public procurement systems, systems that make upwards of 15 or 20 percent of the economy.

What does "public procurement" mean?

"Public procurement" means public purchases made by the government—national, state, city, state-run agencies and enterprises. There are mechanical ways in which procurement can be very transparent and competitive. One way is to run auctions. For example, we've been helping the Mexicans buy medicine. Their medical industry is very fractured. But now we've consolidated the purchasing system, saving around 8.5 billion pesos in two years.

Is the OECD contracted to do that?

Oh, we are very skilled at putting together systems of public purchases that eliminate corruption or at least lower the possibility. How do you do that? By instituting extemporary penalties for those who are caught in the act on top of improving the pay and working conditions of civil servants. Also, encouraging transparency and competition.

Does this also apply to countries where corruption is so deeply entrenched into the fibers of their societies?

If the political will is there, and if there is enough sanction by that society, than it is possible to stamp out corruption. It can be difficult. But we've still made progress. A few years ago for example, bribes were tax deductible in many European countries. And now bribes are not only non-deductible but also illegal in many of those places.

How would you go about dismantling ISIS's financial operations?

I would do what the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has done: follow the money to its source. Problem is a lot of ISIS's funds are cash they receive from doing things like selling oil illegally siphoned from pipelines. So a number of their sources aren't easy to trace back to banks. Bombings as well as the creation of security forces in Iraq that can recapture sieged cities has helped immensely.

What about 2016? What are the OECD's plans?

It's going to be a dramatically busy year. There's COP 21, Nairobi, "21 for 21"—our road map for medium- and long-term issues—as well as our inclusive productivity agenda. We're also working on eliminating tax havens in 130 countries, 97 of which have already agreed to our plan and establishing a base erosion in product shifting that would force multinationals to pay taxes wherever they generate their profits. Moving into the post crisis is another big issue.

What country needs the most intervention? What are the biggest issues?

In terms of places in the world: Europe, Japan and the emerging economies. In terms of issues: bringing back investment, trade and credit. Also, how do you improve morale? Nobody believes in anything anymore. Parliaments, presidents, prime ministers, ministers, political parties, multinationals, banking systems, even international systems—all are subjugated to a great amount of cynicism. So it's very difficult for these governing bodies to propose new ideas because people believe they can't solve their problems.

How do you overcome this skepticism?

By delivering results. We now have eight million more unemployed than we did before the crisis. Before the crisis, economic growth was 4 per cent. Now, it's 3 per cent. Investment was growing at 7 per cent, now it's growing somewhere between 2 and 3 per cent. Same thing with credit and trade: we're going at half-speed.

How do you address the migrant crisis?

We measure flows of immigration in a yearly analysis. We produced indicators to measure the quality of integration of migrants into host societies. Once the migrants are out of the front pages, it will become a problem of integration. We know what it takes to avoid ghetto-ization. The difference with today's crisis is the overwhelming numbers, which has caused resentment.

Interview transcribed by Megan Howell

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.