History is beset by military blunders, from Napoleon's attempt to conquer Russia to America's decision to invade Iraq. But do leaders learn from the mistakes of others?

The authors of the RAND Corporation report Blinders, Blunders, and Wars: What America and China Can Learn look at eight examples of blunders -- and four cases where blunders were not made -- with the aim of warning leaders away from future blunders of their own.

Here is the authors' take on the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

States like [Iraq, Iran, and North Korea] and their terrorist allies constitute an axis of evil. . . . By seeking weapons of mass destruction, these regimes pose a grave and growing danger. . . . I will not wait on events while dangers gather.

—President George W. Bush, State of the Union, January 29, 2002

For us, war is always the proof of failure and the worst of solutions, so everything must be done to avoid it.

—President Jacques Chirac to a joint session of the French and German parliaments, January 2003

President George W. Bush's decision to invade Iraq on March 20, 2003, was not a blunder on the scale of those of Napoleon, Hitler and Tojo.

There was a case to be made on several grounds for operations against Saddam Hussein. The initial phase of combat was highly successful, and some still argue that the American investment was worth the cost of toppling the Saddam regime.

Bush was reelected in November of 2004 as much because of as despite his invasion of Iraq. His subsequent 2007 decision to launch the "surge" did limit some of the damage.

The main premise for the war was that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and that these were at risk of falling into the hands of terrorists. In the end, however, there were no such weapons, and Saddam's links to al Qaeda were unproven. This robbed the invasion of legitimacy.

The insurgency that ensued after initial combat operation robbed the invasion of success. Today, the United States has less influence in Baghdad than Iran does. Iraq is a Shia-dominated state with an alienated Sunni minority, rampant violence and virtually no control over the Kurdish north. At least 134,000 Iraqis died as a direct result of the American invasion, and the violence there continues.

Violent Salafists from Syria and elsewhere have swept through the Sunni areas of Iraq, routing the Iraqi army, seizing important cities and declaring an Islamist caliphate. There were no U.S. military forces available in Iraq to support the Iraqi army.

The Kurds have taken the oil-rich contested city of Kirkuk and hinted at the possibility of separating from the Iraqi state. The United States has been compelled to send military advisors back to Iraq, and it may no longer have enough influence with any of the parties or in Baghdad to preserve a unified state.

Meanwhile, the Afghan conflict was neglected for half a decade. Allied trust in America was eroded, and attitudes about the United States in the Muslim world were poisoned. Some 4,486 American service personnel were killed and more than thirty thousand wounded. The total financial cost by some estimates could approach $2 trillion. Largely because of Iraq, the U.S. public has become very skittish about overseas U.S. combat deployments, especially involving ground forces.5

Major errors included misinterpretation and misuse of intelligence on Iraq's WMD capability, unwillingness to give WMD inspectors time to conclude their work, peremptory diplomacy that damaged the Atlantic Alliance, and failure to properly anticipate what would happen in post-conflict Iraq.

When George W. Bush entered office, "nation building" was anathema.

During the 1990s, the United States would have preferred regime change in Baghdad, but it settled for containment. The 1991 Gulf War ended after one hundred hours of combat with Saddam still in power. Afterward, President George H. W. Bush signed a covert-action "finding" authorizing the CIA to topple the Saddam regime.

During the Bill Clinton administration, no-fly zones in the north and south of Iraq kept Saddam's aircraft grounded in an effort to protect the Kurds and Shias. In February 1998, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright confirmed that U.S. strategy toward Saddam was containment, arguing that removing Saddam would be too costly and that fomenting a coup would create false expectations.6

In October 1998, however, Clinton signed the Iraq Liberation Act, providing funds for the Iraqi opposition. Later in 1998, Clinton authorized a four-day bombing campaign designed to strike Iraqi WMD sites.7 But the Clinton administration never contemplated an invasion of Iraq.

When the George W. Bush administration entered office, its initial focus was on China and military transformation. "Nation building" was anathema. CIA threat briefings concentrated on al Qaeda, not Iraq,8 though efforts to have the new administration deal with al Qaeda failed.

Well before the September 11 attacks, officials at the Pentagon, led by Deputy Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, quietly began to consider military options against Saddam. Deputy National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley developed a policy of phased pressure on Iraq, which included ratcheting up many of the measures used by the Clinton administration, such as sanctions, weapons inspectors, and aid to the opposition.9

That all changed on September 11, 2001.10 Initially, Bush, Wolfowitz and others thought that Iraq might be behind the attacks.11 So did a large majority of the American people, a belief reinforced by the speculation of administration officials.

It became clear that this was not the case, as Bush finally revealed,12 but for many this connection stuck. The first order of business was to destroy al Qaeda in Afghanistan, but the case against Iraq moved rapidly to the front burner. Bush indicated that as soon as the Taliban were driven from Afghanistan, he would turn his attention to Saddam.13

After 9/11, the CIA began to highlight Saddam's WMD capabilities.

The case for invasion resembled a layer cake. At the base was the acute sense of imminent national danger caused by the September 11 attacks. A rogue regime with WMDs and ties to terrorists aroused fear of a much more devastating attack on the U.S. homeland.

Saddam had shown himself for the ruthless villain he was. He had used chemical weapons against his own people and against Iranian troops in the 1980s. He had invaded Kuwait and started a bloody war against Iran. He perpetually threatened Israel. He refused to implement at least ten UN Security Council resolutions aimed at ending his WMD programs and had expelled weapons inspectors in 1998.

In the aftermath of September 11, the CIA began to highlight Saddam's WMD capabilities. The director of central intelligence, George Tenet, revealed eight ways that Saddam might develop a nuclear capability and called the WMD case against Saddam a "slam dunk."14

The CIA had missed several indications that might have given specific warning about the September 11 attack and was not about to be caught off guard again.15 Because the Bush administration had not acted on more-general intelligence warnings of the al Qaeda threat to the U.S. homeland, it would take any future warning much more seriously.

This sense of immediate and extreme danger was amplified in the wake of the September 11 attacks by two other events that cemented the link between WMDs and terrorism. Soon after September 11, anthrax spores were mailed to the U.S. Congress and others, killing five people. Intelligence reports indicated, wrongly it turned out, that Saddam had weaponized anthrax, although he was not suspected of initiating these particular attacks.

If the US could change the regime in Baghdad, it might create a new model of democracy in the Middle East.

Also, the CIA received reports that Osama bin Laden was seeking "dirty" (i.e., radiological) bomb capability, possibly from Pakistan.16 Public concern grew, U.S. hardware stores began to run out of duct tape and pharmacies ran short of ciprofloxacin.

In considering war on Iraq, the sibling of danger was opportunity.17 Some of the neoconservatives around Wolfowitz had held mid-level jobs in the administration of George H. W. Bush. They had seen efforts at regime change work when the United States invaded Panama to topple Manuel Noriega in 1989, when Eastern Europeans cast communism aside that same year, when the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991, and when the Bulldozer Revolution toppled the Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic in the wake of the Kosovo War.

Emboldened by these successes, this group now saw the opportunity to press for forcible regime change in Iraq.

Meanwhile, there was growing recognition that U.S. military power was in a class of its own. The United States had developed new military technologies and tactics that Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld championed as defense transformation.

These included data networking, accurate and voluminous intelligence, instantaneous command and control, and precision strike. Developed in the 1980s and 1990s, they had been on display during Desert Storm and more recently in Afghanistan, where this "military transformation" technology toppled the Taliban regime effortlessly and created a sense of total American military dominance.

By contrast, the Iraqi military had suffered contractions of 35 percent in its army and 60 percent in its air force since before Desert Storm.18 Iraq stood no chance in a force-on-force war.

The thinking went that if the United States could change the regime in Baghdad, it might create a new model of democracy in the Middle East. After all, democracy was on the rise globally in what the political scientist Samuel Huntington called the Third Wave.

Just as it was flourishing throughout Eastern Europe and Latin America, it could take hold in Iraq and serve as a model for the Arab world. Democracy in the Middle East would be a geostrategic game changer, foster stability in that strife-ridden region, and provide America's ally Israel with a much more secure environment.19

The fact that Saddam "tried to kill [his] dad" weighed on Bush's decision making.

In addition, a new regime in Iraq would allow the United States to remove its troops from Saudi Arabia, where they fueled extremism, and to have another friendly source of oil.20 Converting Iraq from an adversary to a friend could also strengthen the U.S. hand—and even provide military bases—against Iran.21

A third and related line of thinking that led to war was a prevailing sense of unfinished business with Saddam—namely, his removal—that needed closure. The United States had been waging a low-grade undeclared war against Saddam since Desert Storm ended as part of its containment strategy. As part of Operations Northern Watch and Southern Watch, the U.S. Air Force flew daily missions over 60 percent of Iraqi territory and was often fired upon, though never hit.22

Other anti-Saddam options seemed to be failing. France and Russia were not cooperating with international sanctions and funds were being diverted by Saddam from the Oil-for-Food Programme to buy arms. In January 2002 the CIA presented Vice President Dick Cheney with an assessment that Saddam had created a nearly perfect security apparatus that made the prospects of a successful coup nearly impossible.23

This unfinished business concerned Bush directly. Saddam had earlier tried to have assassins attack his father while on a Middle East trip. The fact that Saddam "tried to kill [his] dad" evidently weighed on his decisionmaking.24

The concept of preemptive war was deeply flawed.

Finally, after September 11, forcing a regime change in Baghdad made good political sense for the Republicans. The attack on Afghanistan had bipartisan and international support. But the administration needed to be seen as doing more in its declared global war on terror. By going after Saddam they would be well positioned to "wrap themselves in the flag" and compensate for missing the September 11 attacks.25

The 2000 Republican platform had already set the stage by calling for a comprehensive plan to remove Saddam, though without specifically referring to an invasion.26 After September 11, the use of force against Saddam would be difficult for Democrats to protest.

From this logic developed a new national security doctrine of preemptive war. Bush made the case for this during a June 2002 speech at West Point, arguing that the United States could not rely on Cold War concepts such as deterrence and containment to deal with terrorists who are willing to commit suicide for their cause. Neither could it afford to wait for a rogue regime to transfer WMDs to others or gain a decisive capability to harm the United States. It had a responsibility to preempt if necessary.27

During his UN General Assembly speech in September 2002, Bush tied the doctrine of preemption to Iraq, noting "with every step the Iraqi regime takes towards gaining and deploying the most terrible weapons, our own options to confront that regime will narrow."28

This concept was formalized in the September 2002 National Security Strategy of the United States of America, which said: "We cannot let our enemies strike first. . . . The overlap between states that sponsor terror and those that pursue WMD compels us to action."29 The new strategy had general application, but in the context of 2002 it provided the specific strategic justification for an invasion of Iraq.

This concept, born of danger and opportunity, was deeply flawed. The case for Saddam having WMDs turned out to be wrong, and Saddam never had close ties to Sunni terrorists. The preemption doctrine lacked international legitimacy and undermined international trust in the United States.

And yet this flawed concept drove the Bush administration to an early and uncoordinated decision for war, brushing aside the need for analysis, distorting intelligence, marginalizing senior officers who raised doubts and neglecting postconflict stabilization requirements.

Hawks, Doves, Diplomats and the Decider

It is not clear exactly when Bush decided to invade Iraq. Even before the inauguration, Cheney asked outgoing Secretary of Defense William Cohen to provide Bush with a briefing focused on Iraq. Wolfowitz was pushing for military seizure of Iraq's oil fields, which Secretary of State Colin Powell is reported to have called "lunacy."30

Rumsfeld raised the possibility of an invasion on September 11, 2001, as a potential "opportunity."31 On September 17, Bush told his advisors: "I believe Iraq was involved."32 Some in the administration felt that al Qaeda would be unable to organize an attack like September 11 without a state sponsor. With little intelligence to support this assertion, the administration continued to repeat that claim.33

A week after the attack, Wolfowitz began sending memos to Rumsfeld making the case for an attack on Iraq.34 Cheney soon began talking about Iraq as a threat to peace.35 Bush told the British prime minister, Tony Blair, in mid-September that Iraq was not the immediate problem.36 But that changed after the fall of Kabul.37

On November 21, 2001, Bush asked that the war plan for Iraq be secretly updated, which shocked the military.38 By the end of December 2001, Central Command (CENTCOM) Commander Tommy Franks was at the Bush ranch in Crawford, Texas, briefing the President and his national security team on the war plan.39

This early planning did not necessarily reflect a final decision: Some saw it as part of a two-track effort to rid Saddam of his WMDs by using diplomacy and military threats to give diplomacy teeth. But within the next six months, the cement began to dry.

Some speculate that Cheney's change of heart was caused by his bypass operation.

In March of 2002, Bush informally told a group of senators: "We're taking him [Saddam] out."40 That same month, Cheney told Senate Republicans that "the question was no longer if the U.S. would attack Iraq, the only question was when."41 By late July 2002, the British chief of intelligence returned from Washington concluding that military action against Saddam now seemed inevitable.42

National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice "brushed back" State Department concerns about invasion, saying that "the president had made up his mind."43

The three camps in the administration regarding Iraq might be called the hawks, the doves, and the diplomats.44 The hawks were led intellectually by Wolfowitz. Bureaucratically they formed the leading position within the Bush administration in 2002, with Cheney dominating the White House and Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz controlling Defense.

Wolfowitz thought it was a mistake in 1991 to have allowed Saddam to attack Iraq's Shia population after Desert Storm and had favored a demilitarized zone enforced by the United States. Powell opposed him. In the late 1990s, both Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld, out of office, continued to call for Saddam's overthrow.45 Wolfowitz's model in 2002 was the Holocaust, believing that a tyrant who attacks his own people will eventually export that terror.46

Cheney had been a pragmatic internationalist while serving in the George H. W. Bush administration; but according to Brent Scowcroft, he had changed.47 Some speculate that it was his bypass operation, others that it was the psychological impact of being in the White House during the September 11 attacks. Cheney had daily contact with Bush and was his closest advisor on national security matters.

The doves were anything but 1960s tie-dyed peaceniks.

Cheney was described during this period as having a "disquieting obsession" and acting as a powerful "steamrolling force."48 Rumsfeld also strongly supported military intervention, but his principal role was to think about details of the coming conflict and continually refine the war plan to conform it to his notion of military transformation.49

The hawks in government were supported by a combination of neoconservative colleagues and people with connections to the Middle East. Prime among them was a slick American-educated mathematician Iraqi expatriate named Ahmed Chalabi, who was head of the Iraqi National Congress and hoped to return as Saddam's successor. Wolfowitz gave Chalabi access and Chalabi provided intelligence that turned out to be of highly questionable veracity.50

The doves were anything but 1960s tie-dyed peaceniks. They were generally influential pragmatic leaders who were not in the administration. They included the chairman of Bush's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, Brent Scowcroft; the former CENTCOM commander Anthony Zinni, and the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Ike Skelton.

Scowcroft "went public" in August 2002, telling Face the Nation that war with Iraq would be an unnecessary and bad choice that would seriously harm international cooperation against terrorism.51 Zinni's alternative model was Vietnam. He had been badly wounded there and wanted to make sure the cause was just before sending young Americans into harm's way.

The Joint Chiefs cut off debate about the wisdom of an invasion.

While at CENTCOM, he had seen no intelligence that Saddam had WMDs. He wanted evidence. He also felt that those pushing for war had no idea that the war might last ten years.52 Skelton sent Bush multiple questions about the cost and duration of the occupation, noting that he should not "take the first step without considering the last." Skelton was told that the administration did not need his vote.53

Within the military, several senior officers, including Lieutenant General Gregory Newbold and General Eric Shinseki, demonstrated concern about the force structure needed for the operation. But in the fall of 2002, the Joint Chiefs cut off any further debate about the wisdom of an invasion.54 Most in the military were compliant with Rumsfeld's directions.

The diplomats tended to see the same problems that the doves saw, but many were serving in the State Department or wanted to preserve their standing with the administration. Once it became clear that Bush was on a track to war, they sought to find a diplomatic exit or, failing that, to garner international support and create legitimacy for an invasion. This group included Powell and former secretaries Henry Kissinger, James Baker, and Lawrence Eagleburger.55

On August 5, 2002, Powell advised the President that the United States should only attack Iraq if it had a UN Security Resolution authorizing such action. Powell hoped that a UN resolution might force Saddam to back down from his intransigence on WMD inspections—which it in fact did. Powell also told Bush that the United States would "own" Iraq after an invasion and that it would dominate all other foreign- policy initiatives.

Bush's decision-making style was based on his gut instincts.

Bush did not back down from his decision to proceed toward war, but he did agree to give a UN resolution a try. The diplomats may have delayed the invasion by half a year by seeking UN authorization, but once a modest UN resolution was achieved, they lost the ability to prevent war.

Foreign leaders also lined up as hawks and doves. The most important hawk was Blair, who was weary of letting a gap open with American policy.56 Spain's prime minister, José María Aznar, lined up with Blair, while the French president, Jacque Chirac, and the German chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder, eventually opposed invasion. Getting the international consensus Powell wanted would not be easy.

Bush considered himself to be "the decider." After September 11, he seemed "reborn as a crusading internationalist who had embraced Woodrow Wilson's vision of a democratic world and who was willing to use America's military might to make it happen."57

Bush's decision-making style was based on his gut instincts.58 His snap judgment that somehow Saddam was behind September 11, or might be behind the next attack on America, remained with him. Bush felt that September 11 was the "Pearl Harbor of the 21st Century,"59 and that his new and transcending purpose as president was to prevent another, possibly worse, one.60

That early decision solidified during the first half of 2002. Bush was quick to reach decisions, and, once reached, he saw change as a sign of weakness.61 After he reached an early decision on war, he was prepared to try a UN resolution, but not change his fundamental course. He would not let Saddam's new willingness in 2003 to open up to WMD inspectors stop him from invading.62

Rice was Bush's closest confidant. Her primary interest was protecting the President and translating his wishes into policy. But she did not develop the decision-making process needed to analyze and debate the wisdom and implications of going to war. According to Powell, there was no moment when all views and recommendations were aired.63

Nor was there much White House interest in complicated analysis: "They already knew the answers, it was received wisdom."64 There was "no meeting with pros and cons debated. . . . If there was a debate inside the Bush Administration, it was one- sided and muted."65 The urgent sense of danger, the instinct to be bold and the vision of transforming the Middle East trumped debate and analysis.

The worst U.S. intelligence failure since the founding of the modern intelligence community.

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, Tenet presented Bush with a list of countries malevolent enough to help al Qaeda get a dirty bomb: Iraq was on the top of that list. That notion had a profound impact on Bush.66 Bush said: "I made my decision [for war] based upon enough intelligence to tell me that [our] country was threatened with Saddam Hussein in power."67

The case for Saddam's complicity in September 11, or at least for his strong ties with terrorist organizations, was weak.68 The case for his possession of WMDs appeared stronger and drove decision-making. After all, he had used chemical weapons against the Iranians and the Kurds in the 1980s.

But the intelligence was wrong. Iraq had gotten rid of its WMDs. Some say this was the worst U.S. intelligence failure since the founding of the modern intelligence community.69

The intelligence that Bush and others received was based on outdated and incorrect evidence, material from untrustworthy human sources, and worst-case analysis.70 The United States had no reliable intelligence assets in Iraq.71 International WMD inspectors had been kicked out of Iraq since 1998; so in that sense Saddam brought this about himself.

The Pentagon was receiving intelligence from Chalabi, the Iraqi opposition politician, who had an ulterior motive, and from sources such as the aptly named "Curveball." The Pentagon set up a one-off intelligence unit, called the Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group, which began producing "alarming interpretations of the murky intelligence about Saddam Hussein, WMD, and terrorism."72 They were in essence cherry-picking the intelligence in order to draw links between al Qaeda and Iraq and thereby justify intervention.73

In July of 2002, British intelligence concluded that "the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy."74 A State Department intelligence analyst concluded similarly that the administration was looking for evidence to support conclusions it had already drawn.75

The decision-makers and their staffs did not listen to WMD experts like Charles Duelfer, who argued that there was no significant remaining stockpile.76 In fact, they sought to have two intelligence officers removed whose analysis did not comport to their view of events.77

"We don't want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud."

CIA analysts were tasked to prepare a National Intelligence Estimate (NIE).78 They had just been embarrassed by missing the September 11 attacks. Now they were faced with the Pentagon's autonomous intelligence unit, to which the Vice President was listening.

Before the intelligence community rendered its official verdict, Cheney was saying in August of 2002 that Saddam was pursuing a nuclear weapons program.79 Similarly, Rice told CNN: "We don't want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud."80

At the same time a series of leaks to The New York Times put this faulty intelligence on the front pages.81 So while there was no effort by the intelligence community to falsify evidence,82 all of the mistakes tilted in the same direction.83

The NIE was delivered in October 2002 and was considered by many as a warrant for going to war. It concluded, with caveats, that the Iraqis possessed chemical and biological weapons along with delivery systems and sought to reconstitute their nuclear program.84

The body of the NIE contained several qualifiers that were dropped in the executive summary. The fact that the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research disagreed with the conclusions was not highlighted.85 As the draft NIE went up the intelligence chain of command, the conclusions were treated increasingly definitively.86 Only the summary of the NIE was partially declassified, and it omitted most of the reservations and nonconforming evidence.87

The fact that the NIE concluded that there was no operational tie between Saddam and al Qaeda did not offset this alarming assessment.88 A year later, a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report found that the NIE was wrong, that it overstated the case, that statements in it were not supported, and that intelligence was mischaracterized.89

Apart from being influenced by policymakers' desires, there were several other reasons that the NIE was flawed. Evidence on mobile biological labs, aluminum tubing for uranium enrichment, uranium ore purchases from Niger and unmanned-aerial-vehicle delivery systems for WMDs all proved to be false.

It was produced in a hurry. Human intelligence was scarce and unreliable. While many pieces of evidence were questionable, the magnitude of the questionable evidence had the effect of making the NIE more convincing and ominous. The basic case that Saddam had WMDs seemed more plausible to analysts than the alternative case that he had destroyed them. And analysts knew that Saddam had a history of deception, so evidence against Saddam's possession of WMDs was often seen as deception.90

Less than 10 percent of the Senate attended the debate at any one time.

The flawed NIE and associated press leaks had a profound impact on votes in Congress and at the United Nations. At first the administration sought to avoid congressional votes, arguing that they had adequate authority under the 1998 Iraq Liberation Act. Then, under pressure from Powell, they shifted ground and pressed for an immediate vote.

Senators and congressmen and women did raise substantial questions about the nature of the threat against the United States and the need for rapid congressional action. Senator Robert Byrd and Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi in particular questioned the urgency of the vote. Senators Richard Lugar, Paul Sarbanes, Chuck Hagel, John Kerry and Arlen Specter each asked a series of serious questions about the nature of the charges against Saddam. Senators John McCain and Joe Biden and House Majority Leader Dick Armey all questioned the thoroughness of intelligence briefings they received.91

However, less than 10 percent of the Senate attended the floor debate at any one time, causing Byrd to say that the chamber was "dreadfully silent."92 The Republican-controlled House voted first, and then Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle announced that he would support the resolution on the grounds that it was time for Americans to speak with one voice on the issue.93

In October, a congressional resolution authorizing the President to use the armed forces of the United States to defend against the threat posed by Iraq passed with 296 yea votes in the House and 77 yea votes in the Senate.94 All but one Republican senator voted for the resolution.

Many Democrats recalled that a majority of their party voted against Desert Storm, to their regret, and they did not want to make that mistake again. Six Democrats who ultimately ran for President in 2004 and 2008 voted for the resolution.95

At the United Nations, the United States negotiated with France and others for eight weeks and on November 8 passed UN Security Council Resolution 1441 by a vote of fifteen to zero. The resolution, backed by American intelligence, declared Iraq to be in "material breach of cease fire terms" and gave Saddam a "final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations."

But the resolution did not authorize "all necessary means"—that is to say, force—to be used. U.S. Ambassador John Negroponte agreed that another resolution would be necessary to authorize the United States to invade Iraq.

Iraq agreed to the resolution and opened its doors to inspection teams led by Hans Blix and Mohamed ElBaradei, who declared Iraq devoid of WMDs and released forty-three volumes of documentation to try to prove it.96 German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer argued that inspections were "moving in the right direction and. . . they should have all the time which is needed."97

There was no annex in the plan for post-conflict operations.

Meanwhile, Under Secretary of Defense Douglas Feith reportedly told his administration colleagues that inspections were a hazard to the administration's strategy and that they "cannot accept surrender."98 The inspectors were unable to find any WMDs. But Blix reported to the UN on January 27 that Baghdad had not been forthcoming enough in its declarations.99 Later, in 2004, the U.S. Iraqi Survey Group concluded that Iraq had unilaterally destroyed its WMDs in 1991.100

Inspections were moving too slowly for the Bush team. The American military, which had already begun to deploy forces to the region, was in position to invade, and there was a narrowing window to attack before the weather became blisteringly hot.

In February 2003, Powell went to the UN with an intelligence brief based in large part on the flawed NIE. He concluded that the Iraqis were "concealing their efforts to produce more weapons of mass destruction."101 Powell had made an extra effort to personally verify details of his speech with Tenet, and Powell's own intelligence team pointed out several problems with the speech. But many errors nevertheless remained in the text.

Opposition to war was meanwhile mounting in Europe. Blair insisted on a second UN Security Council resolution to bring his country along, but the French feared that a resolution would just be a rubber stamp on a dubious U.S. case for war. In March, when the French threatened to veto a second resolution, Bush dropped the effort and gave Saddam a forty-eight-hour ultimatum to leave Iraq.

With apparently reliable intelligence that Saddam had been spotted on March 19, the attack began by targeting him personally.

In November 2001, at Rumsfeld's direction, Franks began a series of revisions of Operation Plan (OPLAN) 1003, the war plan for the Persian Gulf. Franks's emerging concept embraced Rumsfeld's theory of military transformation, which focused on joint operations, information, speed and maneuver. By March 2002 Franks's command was translating his concept into a plan.

Given Rumsfeld's continual challenges to reduce the force structure and maximize the simultaneity of the attack, the new Hybrid 1003V plan emerged in the fall of 2002. Turkey decided it could not serve as a launch point for an attack from the north, so the plan was modified again for a multipronged attack from Kuwait.

There were massive defections in the Iraqi military as entire units deserted.

The plan focused on winning the war. There was no annex in the plan for post-conflict operations. That would be left up to a newly created Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA).102 The two-day ORHA rehearsal ("rock drill") at the National Defense University just before the invasion demonstrated that postconflict planning was quite primitive.103

By March 19 the United States and its coalition partners had assembled 290,000 military personnel in the region; 116,000 were involved in the march to Baghdad.104 The march to Baghdad was "not only successful but peremptorily short."105 There were massive defections in the Iraqi military as entire units deserted.

There was some tough fighting and sandstorms on the march up, but according to the historian John Keegan, there was "no real war."106 Welcoming crowds of liberated Iraqis never formed. The Iraqi military and their Baathist leaders melted into the countryside, many taking their weapons with them.

On April 9, the U.S. Army occupied the banks of the Tigris River and the U.S. Marine Corps entered Baghdad. Saddam's statue was toppled, marking the symbolic end of the combat phase of operations.107

What were anticipated to be relatively quick and easy post-conflict operations went badly. The ORHA team selected to administer post-conflict Iraq was soon replaced by the more robust Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA).

The CPA made several controversial decisions, which complicated Iraq's reconstruction. It fired Baathists from the top layers of management in government departments; it formally dissolved the Iraqi army (which was in massive disarray anyway); and it shut down state-run enterprises to make way for private companies.

Although mistakes were made during implementation, many of the difficulties experienced by the United States in stabilizing, transforming and leaving Iraq can be traced to errors of commission and omission in the original decision to go to war. For the most part, these difficulties should have been anticipated based on what was known at the time, if not as probable than at least as possible.

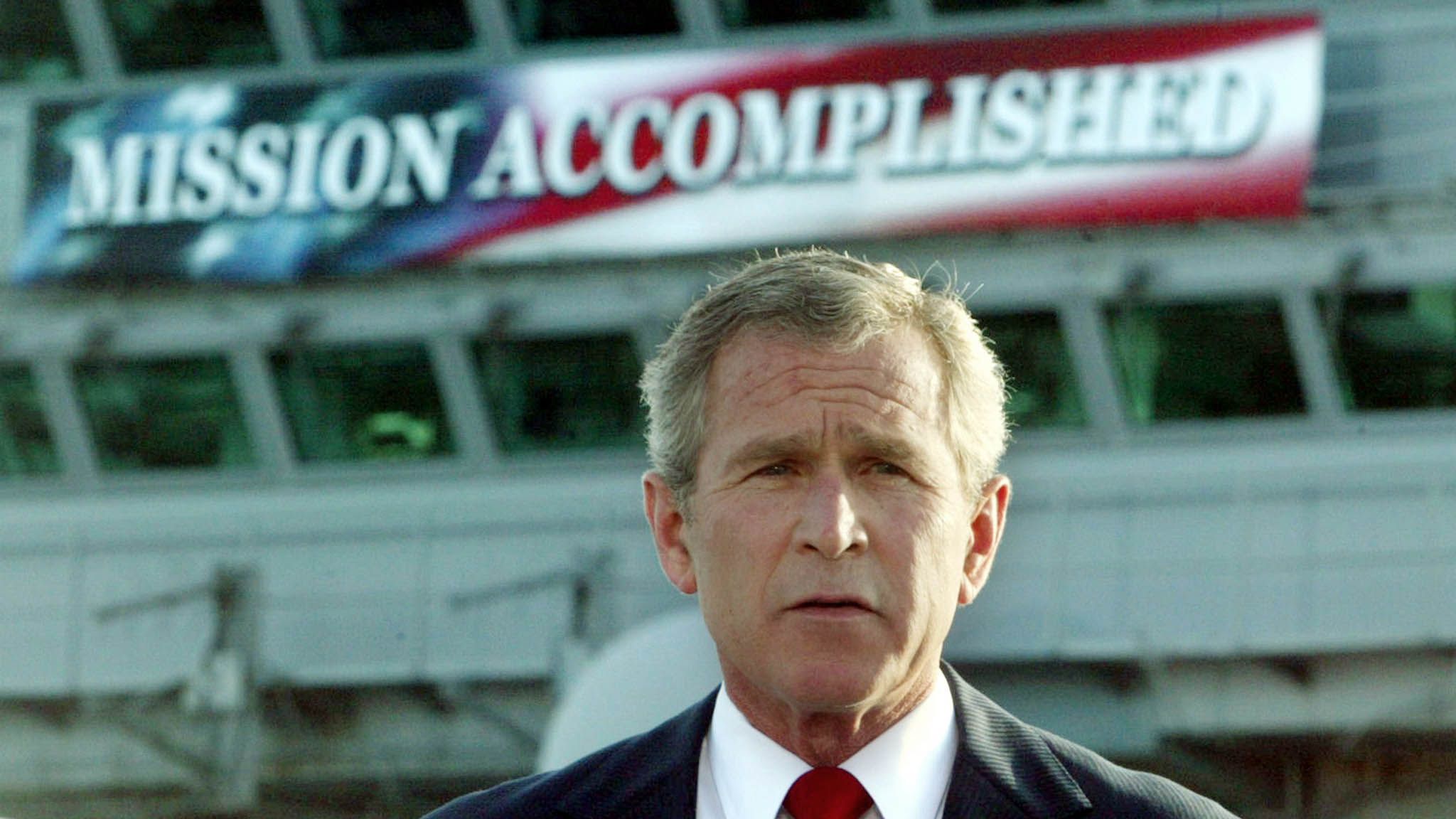

Inadequate provision was made for the travail that would follow "mission accomplished."

The post-invasion model in the minds of those who decided to invade was that Iraqis freed from Saddam's despotic rule would work through a peaceful political process to create a unified, democratic and productive state that would serve as a model for others in the Arab world. The implication was that the demand for American occupation—troops, money, administration, and mediation—would be modest and brief.

If this view was naive, it also was expedient in gaining support for the decision to invade in the first place. To some extent, the proponents of invasion discouraged pre-invasion consideration of post-invasion risks lest it raise doubts or cause delay. In any case, they had unjustifiable confidence in an unrealistic script—namely, that once Iraqi forces were defeated, Baghdad was taken, and Saddam was removed, fighting would subside, a democratic state would emerge, and increased oil production would produce ample revenues to rebuild and transform the country's infrastructure and industry. In any case, inadequate preparation and provision were made for the travail that would follow "mission accomplished."

First, having ruled Iraq since colonial times, large segments of the Sunni minority resorted to armed resistance and then a full-blown insurgency. The U.S. government insisted that the persistent violence was merely the death throes of "former regime elements" and so would quickly run its course.

As the insurgency grew, it opened the door to both foreign and Iraqi religiously motivated terrorists (called "al Qaeda in Iraq"), who attacked the new state and the Shia population, especially soft targets such as mosques and pilgrimages. This then precipitated a Shia backlash in the form of death squads—some from within the Interior Ministry—who targeted not just Sunni terrorists and insurgents but Sunnis in general.

Meanwhile, Shia militias, buoyed by their new political clout and abetted by Iran, attacked the American occupiers.

The U.S. military was unprepared to deal with Sunni uprising, Shia violence, or Sunni-Shia warfare—let alone all three. Eventually, the United States had to increase its troop presence and remunerate Sunni sheikhs to root out insurgents and terrorists.

The failure, or refusal, to consider before the fact that invasion would trigger such turmoil helps explain why the United States left roughly half the forces in Iraq that independent experts and Army officers said would be needed. Those who dismissed such post-invasion dangers and needs were the very advocates of invasion.

The President was not the type to revisit a decision once made.

Besides having too few troops in the country, the U.S. government had programmed insufficient resources. The CPA was understaffed for the post-invasion upheaval it had to try to manage—after all, no such upheaval was anticipated, or its possibility was denied, when the decision to invade was made.

Inadequate funds were earmarked to train and employ the hundreds of thousands of former Iraqi soldiers, security forces, militias and resistance fighters who would have to be "disarmed, demobilized, and reintegrated." As a consequence, there persisted to be large reservoirs of men ready to continue fighting for one side or another, for lack of alternative opportunities.

Compounding the problem of inadequate programmed resources, Iraqi oil revenues did not increase as hoped, mainly because production operations and transport were insecure.

On top of these difficulties, a shortage of competent Iraqis for government, industry and security forces arose because of the way the eradication of the Baath Party was managed. Chalabi and other Shiite partisans took control of de-Baathification and stripped important ministries, companies and security services of capable and needed Sunni professionals from top to bottom.

Predictably—though not predicted—disgruntled ex-Baathists joined the Sunni insurgency. All these problems of poor preparation contributed to and were aggravated by increasingly heavy-handed majoritarian Shiite rule and enhanced Iranian influence.

Post-invasion problems cost the United States dearly in lives, dollars, and goodwill in the Arab and Muslim worlds and beyond. There were plenty of warnings about what faced the United States in post-invasion Iraq. Both the intelligence community and the State Department's Policy Planning Staff produced assessments of post-invasion Iraq that were largely ignored by administration decision-makers.108 And the military understood the requirements of post-invasion Iraq. The administration simply did not listen to the professional military, Foreign Service, or intelligence community.

While several of these problems resulted from mistakes in implementation, many can be traced to the decision to invade. Had the potential for these problems been confronted objectively, preparations could have been made, plans formulated and resources allocated and adequately provided.

However, the architects of war were either too confident to imagine them or, less innocently, afraid that a discussion of risks would undermine political, public, and media support for the invasion. Whether the decision-makers would have decided to invade if these contingencies and consequences had been flagged is moot.

As noted, the President in particular was not the type to revisit a decision once made. At a minimum, if such risks had been identified, they might have been mitigated and the terrible costs to the United States and Iraq might have been reduced.

Why It Went Wrong

The strategic environment immediately after September 11, 2001, was filled with a sense of urgency and imminent danger. Bush felt a heavy burden of responsibility for protecting the nation. Even after it was known that Saddam was not complicit in the attacks on America, there was concern that he might provide WMDs to terrorists, who would eagerly use them on America.

In this environment different factors conspired to lead Bush to a decision to pursue an optional war that most Americans believe in retrospect did much more harm than good to their interests.

The first factor was an effort by a group of neoconservatives in and out of government to seek opportunity in danger. They saw an opportunity to rid the Middle East of a dangerous dictator and create a new democratic model for the region. They shaped an attractive vision of what might be that turned out to be far from the mark.

The second was an effort by the Policy Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group in the Pentagon to cherry-pick selective intelligence from questionable sources and the subsequent failure of the actual intelligence community to prevent some of that questionable intelligence from making its way into the NIE and the public domain. That selected and dubious intelligence reinforced concerns about the danger posed to the United States by Saddam. Reservations carefully placed in the NIE by the intelligence community were buried in the body of the report.

The third was a sense of prowess and hubris from a string of successes by a transformed high-tech military that created the belief that expeditionary warfare is decisive, quick, easy, and low-cost.

The fourth was a dysfunctional and opaque decision-making process that rejected much analysis available in and out of government and that never formally brought the cabinet officers together to discuss the pros and cons of waging war.

The fifth was impatience on the part of the Bush team to wait for the results of the arms inspectors who were making progress in Iraq, results that could have obviated the need for war. That impatience led to lost support from key American allies, such as France and Germany.

The final flaw in the decision chain was the failure to prepare for a post-conflict occupation and stabilization program; that failing initially resulted in anarchy and then civil war.

Throughout, those who preconceived the war used information selectively, marginalized dissent and evaded analysis that could threaten their preconception. They had a compelling model, but it did not reflect reality.

Authors

David C. Gompert is an Adjunct Senior Fellowat the RAND Corporation, Hans Binnendijk, is a former National Security Council senior director for defense policy and an adjunct senior researcher at the non-partisan, non-profit RAND Corporation and Bonny Lin is an Associate Political Scientist at the RAND Corporation. This essay first appeared on the RAND Corporation's website.

Sources

Sources used for this case include: Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004; Lawrence Freedman, A Choice of Enemies: America Confronts the Middle East, New York: PublicAffairs, 2008; Richard Haass, War of Necessity, War of Choice, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009; Michael Gordon and Bernard Trainor, Cobra II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq, New York: Vintage Books, 2007; Thomas E. Ricks, Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq, 2003 to 2005, New York: Penguin, 2007; Jervis, 2010; Betts, 2007; Pillar, 2011; Bing West and Ray Smith, The March Up: Taking Baghdad with the 1st Marine Division, New York: Bantam, 2003; James Dobbins et al., Occupying Iraq: A History of the Coalition Provisional Authority, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, MG-847, 2009; John Keegan, The Iraq War, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004; Richard Clarke, Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror, New York: Free Press, 2004; Tommy Franks, American Soldier, Norwalk, Conn.: Easton Press, 2004; Alexander Thompson, Channels of Power, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2009.

This is a chapter from the RAND Corporation report Blinders, Blunders, and Wars: What America and China Can Learn. Other chapters contain assessments of: Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, 1812; The American Decision to Go to War with Spain, 1898; Germany's Decision to Conduct Unrestricted U-boat Warfare, 1916; Woodrow Wilson's Decision to Enter World War I, 1917; Hitler's Decision to Invade the USSR, 1941; Japan's Attack on Pearl Harbor, 1941; U.S.-Soviet Showdown over the Egyptian Third Army, 1973; China's Punitive War Against Vietnam, 1979; The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, 1979; The Soviet Decision Not to Invade Poland, 1981; and Argentina's Invasion of the Falklands (Malvinas), 1982.

You can download the complete report here:

PDF file (1.9 MB) - Best for desktop computers.

ePub file (4.5 MB) - Best for mobile devices.

mobi file (10.1 MB) - Best for Kindle 1-3.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.