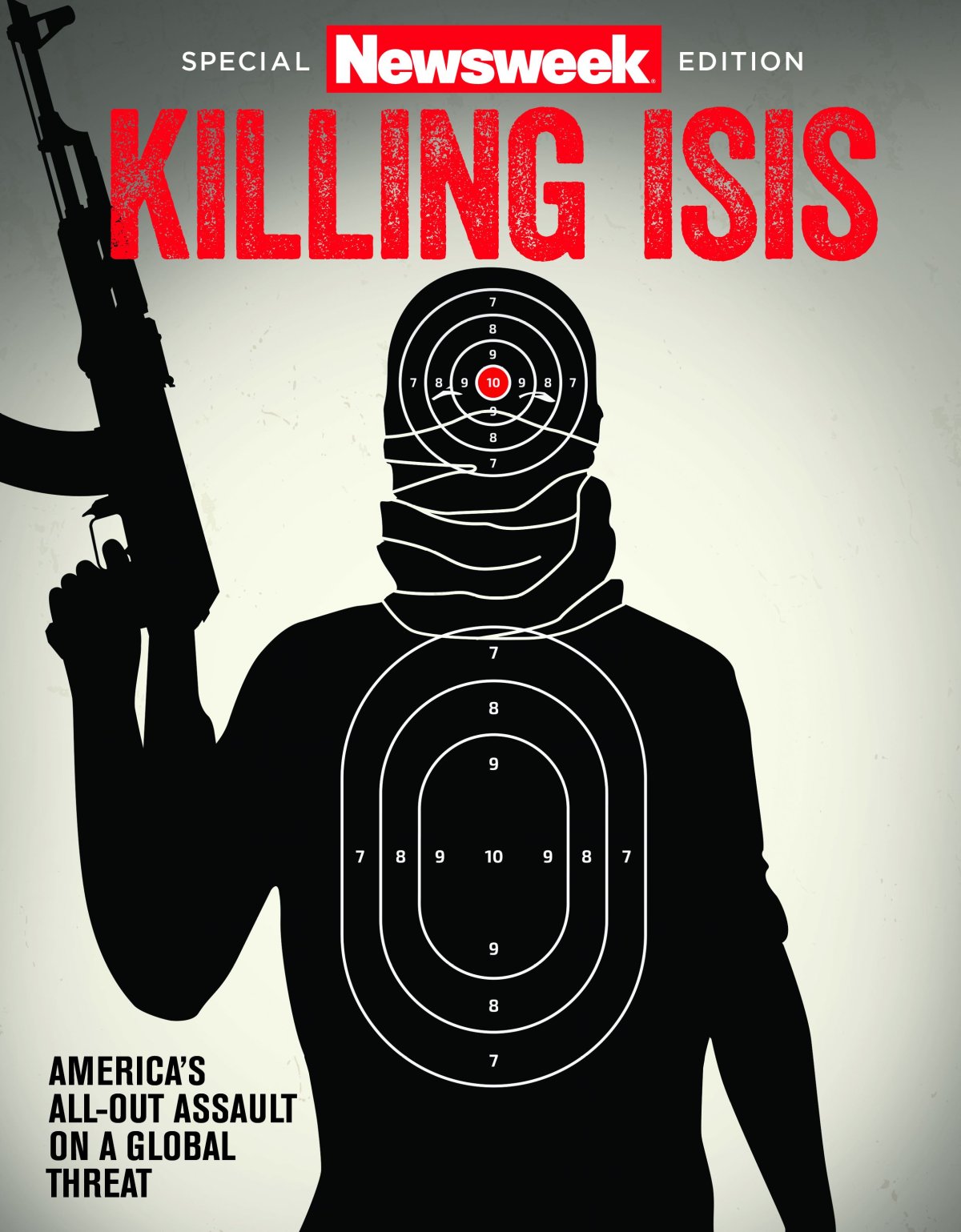

This article, written by Issue Editor James Ellis, and other articles about America's assault on its greatest terror threat, are featured in Newsweek's new Special Edition, Killing ISIS.

Al-Qaeda's leaders were wary of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian street tough who later embraced jihadism. When he first appeared on Al-Qaeda's Kandahar doorstep in 1999 seeking financial support, Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri deemed him too eager to condemn other Muslims, needlessly making enemies on all sides. Al-Zarqawi's approach was anathema to their plan to liberate Muslim lands from Western domination, which required mobilizing a popular Muslim front against the United States. Al-Zarqawi, for his part, found the men too tepid and tolerant of theological lapses. They agreed to be friends but nothing more. Al-Qaeda's leaders gave al-Zarqawi seed money to set up his own training camp for jihadists from the Fertile Crescent and the Levant.

Ever the terror venture firm, Al-Qaeda couldn't resist a chance to train jihadis from a part of the world where they had few operatives, even if it was deemed a risky investment.

When the United States invaded Afghanistan after 9/11, al-Zarqawi fled with some Al-Qaeda operatives to Iran. Heartened by news that the United States would soon invade Iraq and inspired by stories of a medieval Muslim conqueror who overthrew Crusaders and ruled the land between Mosul and Aleppo, al-Zarqawi conceived a plan to reestablish the Islamic empire in its historical heartland. He would burn Iraq to the ground after the U.S. invasion and resurrect the caliphate from its ashes.

Al-Zarqawi set his plan in motion before the first American boot hit the ground, dispatching operatives to Baghdad in 2002. When the United States invaded in 2003 and disbanded the Iraqi military and security services, al-Zarqawi worked with former regime loyalists to destabilize the country and plunge it into a sectarian civil war between the minority Sunni and the majority Shiite.

Al-Zarqawi explained his strategy in a letter he wrote to Al-Qaeda's leaders in 2004. He would kill Shiite civilians—irrespective of the rules governing Islamic warfare—to provoke the Shiite majority to retaliate against the Sunnis, who would be forced to turn to the jihadists for protection. Al-Qaeda was leery of the strategy and of the mind that had conceived it, but it needed operatives inside Iraq. Al-Zarqawi was happy to oblige in return for Al-Qaeda's label, which he hoped would attract foreign fighters to his cause.

It was a marriage of convenience Al-Qaeda would soon regret. Al-Qaeda's leaders chided al-Zarqawi for killing civilians and distributing videos of gruesome beheadings. Such tactics would alienate Sunni leaders, they complained, and make it impossible to ally with them against the American occupation and the Shiite government in Baghdad. Without popular support, Al-Qaeda warned, al-Zarqawi would be unable to establish an Islamic state, much less a caliphate. Al-Qaeda also cautioned al- Zarqawi against proclaiming a state until the jihadists had persuaded the Americans to leave. No nascent state could hope to thrive in land occupied by the world's most powerful military.

Al-Zarqawi turned a deaf ear. The attacks on civilians, Sunni and Shiite, continued, and al-Zarqawi announced an Islamic state was about to be established. When al-Zarqawi was killed by the Americans in the summer of 2006, his successor proclaimed Al-Qaeda in Iraq was no more; its soldiers now fought for the brand new Islamic State of Iraq.

Al-Qaeda's leaders fumed—they had not been forewarned of the Islamic State's establishment. The leaders of the State placated them by pledging a private oath of allegiance to bin Laden. But the group continued to publicly present itself as a state, independent of any organization.

Behind the scenes, the relationship grew further strained. Al-Qaeda demanded regular reports on the disposition of the Islamic State's fighters and offered pointed counsel on how to advance the State's agenda. The Islamic State waved it away as mere advice, the distant frettings of men who had no clue about the rough realities of Iraqi insurgent politics.

The only times the Islamic State acceded to Al-Qaeda's wishes was in regard to external operations. The Islamic State's soldiers desperately wanted to take the fight to Iran and Saudi Arabia, which Al-Qaeda vetoed for one reason or another. The Islamic State grudgingly bent the knee.

When the Syrian revolution slid toward civil war in 2011, Al-Qaeda ordered the Islamic State to dispatch some of its operatives there to build a terror network. The Islamic State's secret Syrian branch, called the Nusra Front, initially behaved like the Islamic State, carrying out attacks without a care for civilian casualties. But over time, Nusra began to follow the advice of Al-Qaeda's leadership, which cautioned its members against killing Sunni civilians and counseled them to embed in the broader insurgency against the ruling regime. The strategy was at odds with the Islamic State's plan of going it alone.

The incompatible strategies ultimately led to a rupture between the Islamic State and Nusra. After failing to quietly bring Nusra to heel, the Islamic State's leader announced publicly that Nusra had been a secret branch of the Islamic State all along. Nusra's leader responded by denying the Islamic State's authority and pledging a direct oath of allegiance to Al-Qaeda's leader, al-Zawahiri.

When al-Zawahiri ordered the Islamic State to confine itself to Iraqi matters, the Islamic State refused. Al-Zawahiri responded by divorcing Al-Qaeda from the Islamic State; the State denied they had ever been married in the first place. Two years of bloodshed and acrimony followed, particularly after the Islamic State proclaimed itself the caliphate reborn and demanded that Al Qaeda and all other Muslims obey its commands.

From time to time, al-Zawahiri has held out an olive branch, saying he would fight alongside the Islamic State if he were in Iraq. But he refuses to recognize the statelet as a caliphate and dismisses it as a front for former Saddam loyalists. The Islamic State dismisses al-Zawahiri as a has-been and deems the Al-Qaeda project a failure compared to the achievements of the caliphate.

The feud between Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State is playing out on the global stage. The State orchestrates and inspires attacks in the West to rival those of Al-Qaeda. It sets up local chapters in the countries where Al Qaeda has franchised. The competition is not only for recruits but also for custody of the jihadist enterprise to establish Islamic states: the brawling, winner-take-all Islamic State versus the cerebral and cooperative Al-Qaeda. The world suffers while the feud endures.

William McCants is a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution, where he directs the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. He is the author of The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State.

This article was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition, Killing ISIS, by Issue Editor James Ellis. For more about America's assault on our greatest terrorist threat pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.