Daniel Rye Ottosen has just returned to the Malawian town of Chikwawa from a week in the bush with a small family, surviving on a bland dough known locally as nsima. The austere diet reminds the 27-year-old Danish freelance photographer of harder times.

"Right now, I am looking forward so much to having a decent meal, to drink cold water. Some of the feelings that I had back in Syria, I can feel it again," he says, speaking by telephone from a Red Cross office in a rare interview with Newsweek.

Ottosen's hunger in Syria was not from photographing his subjects, hunkered down in areas ravaged by war, but due to meager and sporadic bites of olives, eggs and bread throughout a 13-month ordeal in squalid captivity at the hands of the Islamic State militant group (ISIS). The group kidnapped him on May 18, 2013, at the end of a three-day excursion into Syria, a three-day trip that quickly snowballed into a 13-month nightmare.

It is Ottosen's imprisonment that serves as the subject of Middle East reporting veteran Puk Damsgård's The ISIS Hostage: One Man's True Story of 13 Months in Captivity. It provides a captivating account of his days inside the early incarnation of the ISIS machine, where he was only kept alive as a financial pawn, and a dramatic tale of hostage negotiation and family sacrifice. It is the only instance that Ottosen has publicly communicated his full story, entrusting Damsgård with every detail of a journey defined by humiliation and sheer savagery at the hands of his radical Islamist captors but also an esprit de corps with his fellow prisoners.

"This was my way of collecting my total story into one. So people who are interested in knowing what really happened, can sit down and not read 10 different articles with a lot of bullshit, but the story as it was," he says, audibly aggrieved by the sensationalization of his and his friends' torture. "Why did I go? What happens to people when they go through such things?"

Four days before his kidnap, Ottosen flew from Copenhagen to the Turkish city of Gaziantep, on to the border town of Kilis before crossing into Syria and reaching the northern town of Azaz. He had sought to photograph Syrians who were attempting to make the most of their life amid a two-year-long civil war.

Kidnap

On his final day in northern Syria, Ottosen and a fixer attempted to obtain permission from the "local authorities" to film in the area but upon interrogation, they detained him, accusing him of being a spy. The local authorities were from Dawlah al-Islamiyah, or ISIS, the group that would rise to global prominence a year later in a lightning sweep across Iraq and Syria.

Ottosen would be moved location a total of eight times as an ISIS prisoner. First, ISIS held the Danish photographer at two locations in Azaz, before he was moved around three locations in the northern city of Aleppo, the first a torture center under the watch of brutal guard Abu Hurraya and his superior Abu Athir, who had spent time in Bashar al-Assad's Sednaya torture prison; then to two other torture prisons, one underneath a children's hospital and the other in the Sheikh Najjar district northeast of the city.

ISIS then transferred Ottosen to an unknown location that hostages refer to as the "Five Star Hotel" because of the food they were given. He was moved one more time before reaching Raqqa. His final destination would be a prison complex known to the captives as "The Quarry," south of the group's de-facto capital of its self-proclaimed caliphate, alongside 23 other hostages—five women and 18 men—where they would meet the infamous "Beatles," a British gang of torturers.

Ottosen, a blonde, pale former gymnast, shared his trauma with hostages of 13 different nationalities and, while government-sanctioned ransom payments freed many of the European hostages, ISIS killed six of his friends while in captivity. The ISIS executioner Mohammed Emwazi, widely known as Jihadi John and part of "The Beatles" gang, decapitated five of Ottosen's cellmates—U.S. journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, U.S. aid worker Peter Kassig and British aid workers Alan Henning and David Haines—for propaganda purposes. U.S. aid worker Kayla Mueller also died in captivity.

Family

Capitalizing on a Danish legal loophole, his family and friends, aided by a secretive hostage negotiator named Arthur who had warned Ottosen not to travel to Syria, embarked on a race against time to locate their son, brother and friend. A prison visit by Arthur to Belgian jihadi Jejoen Bontinck provides the key breakthrough. The family proceeded to raise 15 million Danish kroner, the equivalent of €2 million euros ($2.23 million)—a sum only slightly cheaper than the €2.5 million ($2.8 million) that France paid for its ISIS hostages—for his release. He touched Danish soil again on June 20, 2014.

"When I was released I had no intentions or interest in making a book at all, but when I came home I started to understand that this whole situation was about much more than just my own experience," he says. "I felt that [my family and friends] deserved the full story about what happened to this person that so many people suddenly helped and paid money to. This is kind of a tribute to these people."

This was a feat that the families of Foley, Sotloff and Kassig were not permitted to attempt because U.S. law forbade them. Following the deaths of Foley, Sotloff, Kassig and Mueller, President Barack Obama opened the door for families to negotiate with extremist groups in a review of U.S. hostage policy in June 2015. After Ottosen's family successfully secured his release, he says that working on The ISIS Hostage has served as a cathartic medium through which he and his loved ones could understand what the other had truly experienced while he was in ISIS's hands.

"It's very difficult to sit down and tell each other what happened. It's difficult for me to sit down and tell my Mum how they tortured me. It's difficult for my Mum to tell me how she was crying behind a big container in Legoland where she was working," he says, adding that learning about the ordeal of his mother, Susanne, was the hardest part of the whole project.

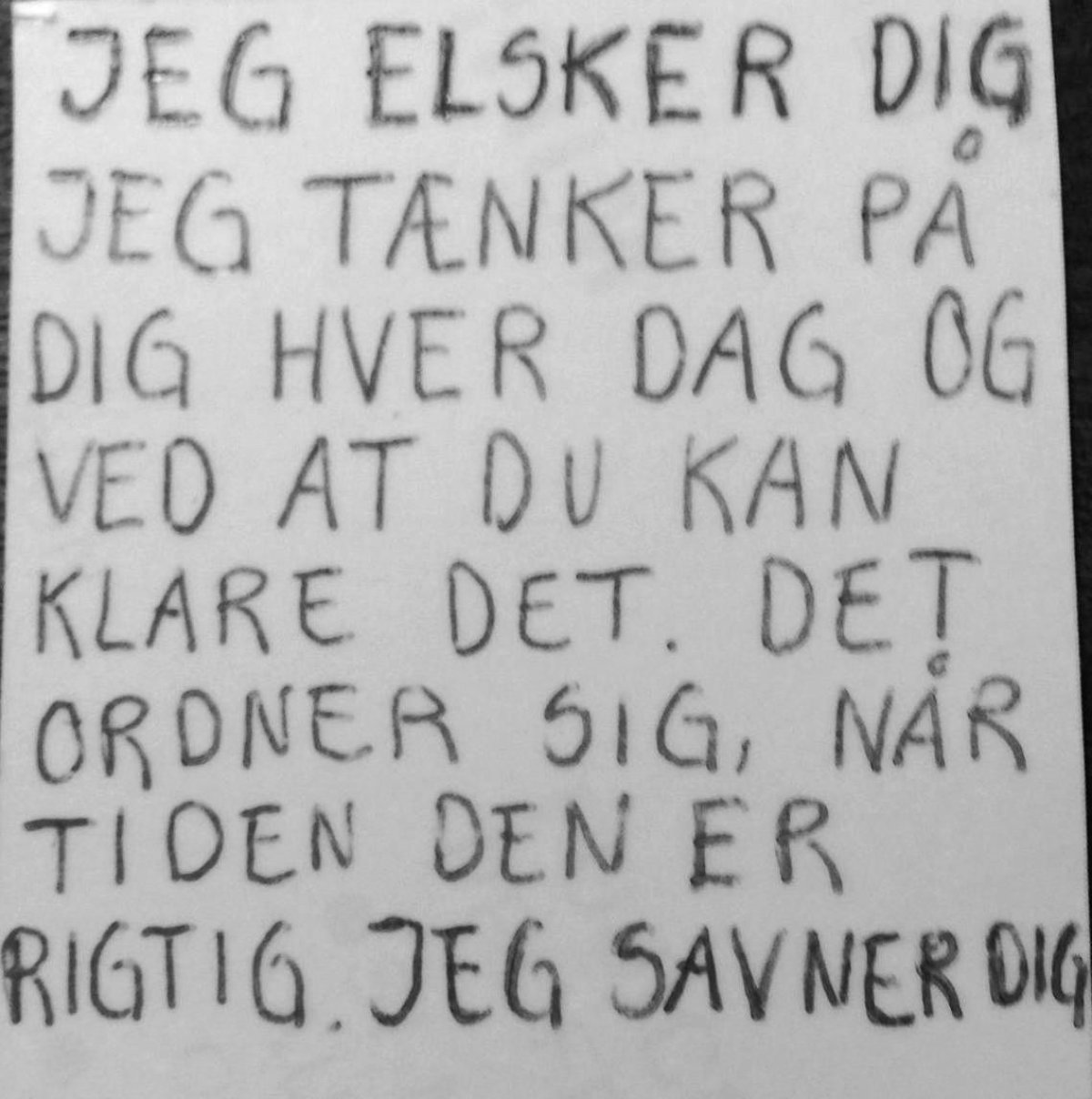

Every morning during her son's captivity, she would listen to "Small Shocks" by Danish band Panamah, crying throughout its three-and-a-half minutes, which begins with the lyric: "Will you come back home?"

His family is a strong unit—Ottosen is sandwiched between an older sister, Anita, and a younger sister, Christina—shaped by the loss of his biological father when he was three years old. But traveling home to the small village of Hedegård, in Denmark's Jutland region, is a challenge for Ottoson, who feels overwhelmed by the amount of money that others stumped up to save his life. He now lives in Odense, Denmark's third-largest city.

He was himself weighed down by debt to the tune of $130,000 after his release, as his family not only raised the ransom payment through donations, but also through bank loans. The ISIS Hostage, released in October 2015 in Danish, garnered enough domestic attention that he delivered lectures and speeches about his ordeal, allowing him to pay off his entire debt. Some of his fellow survivors did not want a book to be written, he says, but once he explained his reasons—fixing his family's arrears and giving the full account to all of the donors who contributed—they began to understand his motives.

"One of my first priorities since I came home has always been to go back to the life I had before. And to be able to do that, I had to pay off my debt," he says unashamedly, as focusing on clearing this sum gave him a goal and a life to cope with life outside of captivity. "When I came home, my project was to pay off this money. You have to remember that I left six of my very good friends behind and for them I could not do much."

His fellow prisoners had even warned him that, if he was released, he had better sort his life out. "They told me, 'Daniel, if you go back home and you don't appreciate your life, we will come and kick your ass!'"

Ottosen remains the last Western hostage to be released by the group, but not because of the Danish government, who he says have "done nothing" for him or his family since his release. He accuses Copenhagen of giving returning Danish foreign fighters "more help than I got."

Torture

Some of the book's most difficult moments come while Ottosen is in Azaz, particularly under the guard of Abu Hurraya, a burly, pony-tailed Syrian torturer, before he is introduced to his fellow Western hostages later in his ordeal. The photographer is subjected to 'The Tyre' torture technique, where a tire holds the victim's legs in place so they can't move, allowing the soles of their feet to be whipped repeatedly. Hurraya starves Ottosen of food and water, extending him from a cell ceiling by his chained wrists. It becomes so insufferable that Ottosen attempts to bite through his limbs to escape and, eventually, attempts suicide. He also contemplated converting to Islam but feared making a "fool of their religion" and paying the price.

"I think the good thing was that I experienced almost all the worst things in the beginning because that hardened me up. That made me realize what these guys were capable of," he says. "If I was released after one month, after my whole torture, I don't think I would have been able to come home and been a normal person, I don't think I could go directly from torture to freedom."

Life became more bearable for Ottosen when he had other Western hostages to talk to and, eventually, a fellow Danish hostage. Their shared experiences helped him develop an "iron coat" to the ISIS beatings. But he saw Hurraya as simply carrying out his role as an interrogator, whereas the British Beatles—made up of Londoners Emwazi, Abdel Bary, Alex Kotey and Aine Davis—"tried to make it personal," wantonly delivering beatings for little reason. "They were not told to go in and beat us up, I don't think so, but they did it because they wanted to, they enjoyed it," he says. They also regularly humiliated the hostages, making them tango with one another, and sing songs about Kenneth Bigley, the hostage beheaded by Al-Qaeda in Iraq in 2004, and repeat takes for staged propaganda videos.

Amid the grim tales of hostage hygiene, beatings and suicide attempts in Ottosen's account, there are also glimmers of hope triumphing over hate. Of his captors, he says that if they were standing in front of him today, he would not hurt them, but engage with them, asking why they carried out such barbaric acts of violence. He views them as individuals who did not have the same fortune of a good upbringing.

"I do not think that any of them were evil. I remember in the schoolyard when I was a kid, and ever since I've been a gymnastics teacher, some of the kids who are the weakest are also the ones who do cruel things to protect themselves and to hide their weaknesses," he says. "So I think some of the people who were very violent to us had issues. You do it because you need to prove something to somebody. I feel a little bit sorry for some of them."

Camaraderie

The ISIS Hostage captures an inspiring message about the collective reaction of humans to such brutal trauma. There are the inevitable disagreements over food (portion sizes), space (who is nearest the toilet bucket) and hygiene (lice) with so many people crammed into a few square meters.

But the Western hostages comforted one another after beatings, created games, excitedly shared food and started their own gymnastics and yoga classes, which Ottosen and Sotloff led respectively. The quest to help each other through the daily torment left Ottosen with enough "funny memories" to fill a second book, he says. He recalls one of his fondest moments from his captivity, a moment of dark humor with Foley that is not detailed in the book.

"One time, while I was teaching him gymnastics, he told me that he could not continue because he was too tired and had no energy. He said 'I just need five minutes.' He went down and ate a piece of bread and five olives. Then he came back like, 'Oh, now I have energy.'

"Half a year later, at the last place where we received more food, we were talking about this situation, we looked back about how we were doing, and how bad we were looking, and how little food we were getting. We talked about how James suddenly got a lot of energy from bread and olives, and we both just started laughing so hard. We really laughed about how weak and how miserable we were. It was funny, but also it was our way of taking the piss out of the situation."

Ottosen says he is more motivated than ever to capture important stories across the world with his camera. He is content with a book that he says will finally bring him closure, more than two years after his release. While he believes that it is important to live with the experience of those harrowing 13 months, a new chapter in his life, informed by the past, is beginning. "Every day is a step closer to not being that guy."

THE ISIS HOSTAGE One Man's True Story of 13 Months in Captivity by Puk Damsgård, published by Atlantic Books, £9.99.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jack is International Security and Terrorism Correspondent for Newsweek.

Email: j.moore@newsweek.com

Encrypted email: jfxm@protonmail.com

Available on Whatsapp, Signal, Wickr, Telegram, Viber.

Twitter: @JFXM

Instagram: Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.