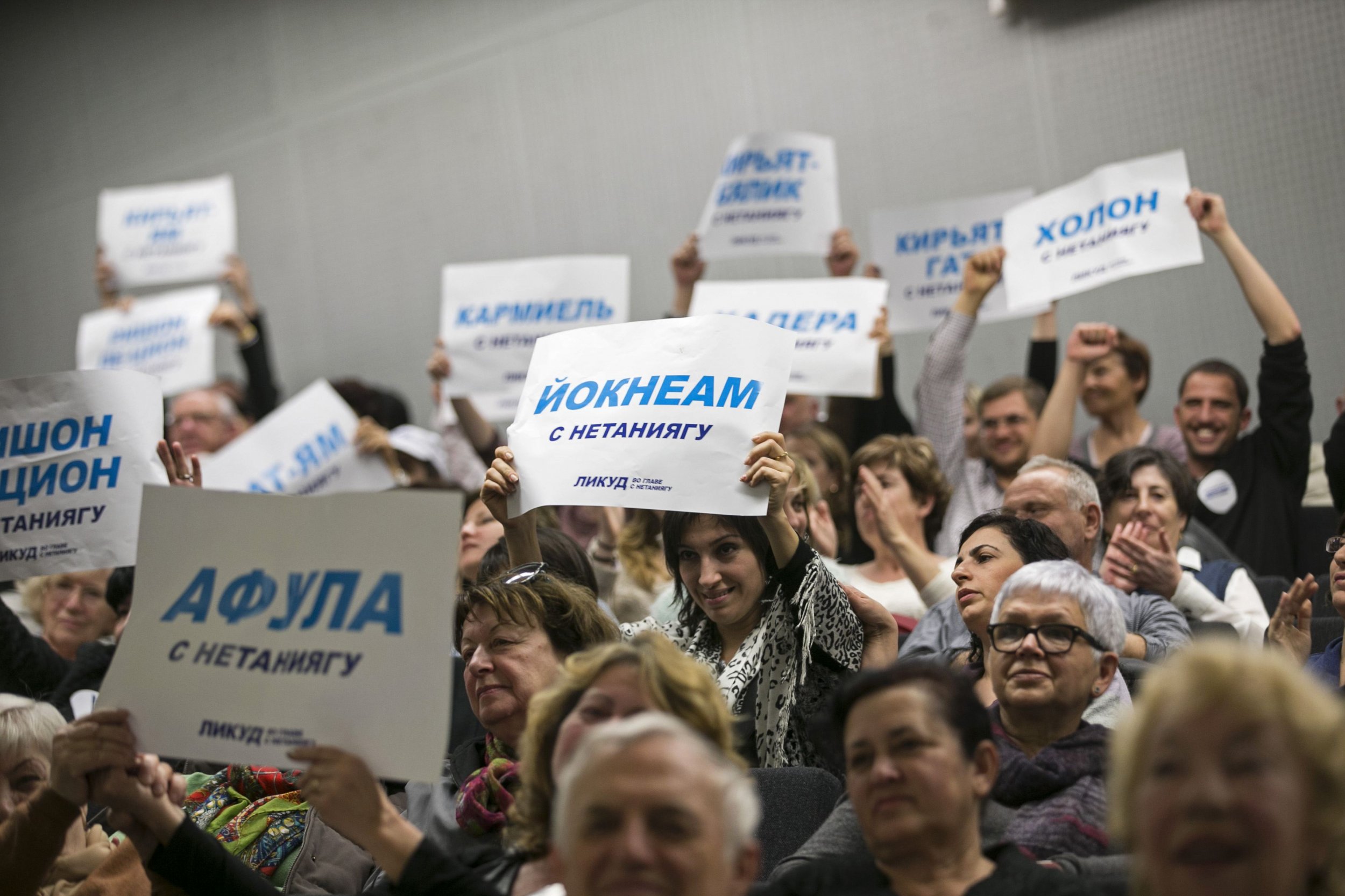

Israel's election campaign continues day after day, hot and heavy, with five weeks to go. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has struck a blow with the best campaign ad so far, and it can be found here with English subtitles.

But the race is very close, and analyses and polls in The Times of Israel help explain why. As a new article states,

If Isaac Herzog wins the upcoming elections, it will be because voters have become disenchanted by Benjamin Netanyahu rather than been won over by the Zionist Camp leader [Herzog], a Times of Israel survey shows.

Herzog, known as "Buji," remains remarkably little known to Israelis despite his years in the Knesset and in public life: a remarkable 20 percent of voters say they have no opinion of Herzog or have never heard of him. According to another story in The Times of Israel, one-fourth of all Israelis remain undecided about their vote–and they are in large part centrist voters who "have soured on Netanyahu, giving him lower personal and job approval ratings and edging in the direction of Herzog's Zionist Union." As the article, by Stephan Miller, says,

undecided voters hold even more negative views, with 19 percent giving him a "excellent" or "good" rating and a 71 percent a "fair" or "poor" rating. The more this election is a referendum on Netanyahu and his performance as prime minister, the worse Likud will fare.

But Israelis don't get to vote for prime minister directly; they vote for parties, and the party with the most seats in the Knesset gets to try to form a new coalition government. Usually–that is. Sometimes the president of Israel will instead–if the top two parties are very close in seats–turn to the party that he thinks, after consultations with the leaders of all the parties, will be better able to form a new coalition. That could well be Likud, Netanyahu's party, even if Herzog gets one or two more seats. As The Times of Israel explains,

Still, even with a strong showing on election day, the Zionist Union would find it challenging to build a coalition of 61 or more seats in the Knesset in order to form the next government….

This is precisely what happened in 2009, when Tzipi Livni's Kadima Party got more seats (28) than Netanyahu's Likud (27), but did not get the nod from then-president Shimon Peres to form the new government.

So, the race is close and likely to remain so right through election day on March 17. Herzog has five weeks to define himself for Israelis before he gets defined by his opponents in Likud. Protest votes against Netanyahu won't much help Herzog unless he gets them: if Likud gets the most seats in the Knesset Israel's president will turn to Netanyahu again to form a government, and if the "fatigue with Bibi" voters turn to centrist or conservative parties that would rather join Netanyahu's coalition than Herzog's, once again Netanyahu will remain prime minister.

It isn't surprising that there is fatigue with Netanyahu, who has served as prime minister for a total of ten years. After all, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair faced some of the same problems after their ten years at the top. But the British party system is unique and lends itself to internal party putsches of the sort that toppled Thatcher and Blair.

In Israel, the question isn't whether voters are tired of Netanyahu and wish there were someone else they could have full confidence in and support; that seems true. The question is whether they will find that person in Herzog. If not, Netanyahu will have several more years in office.

Elliott Abrams is Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. This article first appeared on the Council on Foreign Relations website.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.