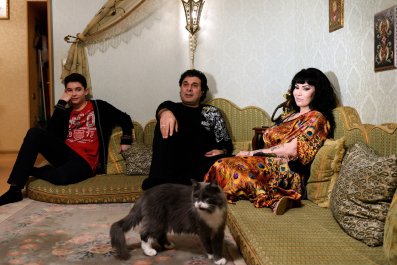

Everywhere I look inside Irit and Asher Shahar's house, I see their dead son: His face greets me from the framed photos on the wall, a bronze statue by the kitchen and on a medallion around Asher's neck.

Four years ago, his parents learned of his death when a representative from the Israeli military knocked on their door in Kfar Saba, a town in central Israel. He came inside, put his hand on Asher's shoulder and told the Shahars and their two daughters what had happened: Omri, an officer in the Israeli navy, had died in a car crash. He was 25.

Irit collapsed on the couch and burst into tears. "I want you to take the sperm out of his body," she demanded.

The representative shifted uncomfortably in his seat.

"You're going to need a court order to do that," the Shahars recall him saying.

Asher, a former officer in the navy, stared back at him. "Then what are we waiting for?"

The two men drove to a courtroom in Petah Tikva, where Asher asked a judge for permission to harvest his son's semen. The judge agreed, and a doctor carried out the procedure, but the family hardly felt relieved. "There was no joy in getting that court order," Asher says. "It was a day where happiness was not possible."

The joy came this fall, after a lengthy legal battle with the state. The Shahars wanted to buy an egg from a donor, hire a surrogate mother to carry it and create a grandchild with their dead son's sperm—a child they would raise as their own. But the state argued this was unethical, that the baby would grow up with a dead father and an anonymous mother. The ability to use the seed of a dead son to create new life, the government argued, should be reserved for the husband or wife of the deceased. In a landmark ruling on September 27, however, the judge sided with the Shahars.

"A branch from our family tree has been cut, and there is nothing we can do about it," Irit says. "But because of the new technology, we can make sure new leaves appear. We simply wish for the grandchildren that should have been."

The Shahar's aren't the only ones. Not only are more and more Israeli men freezing their sperm before going off to war, but a growing number of parents and spouses are extracting semen from their loved ones after their deaths. The goal: to pass on their genes.

Depending on the cause of death, experts say, sperm can be collected for up to 48 hours after someone passes. Usually, doctors do so by surgically removing the testicles. The sooner the operation is performed, the better the quality of the sperm cells.

The process has existed for decades. But since the late 1980s, several countries, including Germany, France and Sweden, have banned it for ethical reasons, even when there's written consent from the deceased. Israel had similar ethical concerns. In 2003, the government published rules that drew heavily on Jewish texts. Procreating, the guidelines mention, is the first mitzvah, or good deed, mentioned in the Bible: "Be fruitful and multiply," God commands Noah and his sons in the book of Genesis. Yet the guidelines also made it clear that the right to retrieve sperm for in vitro fertilization is solely reserved for the partner of the deceased.

The Israeli judicial system has slowly eroded that position. In 2007, a court allowed the parents of a soldier who died in Gaza to produce a grandchild using their dead son's sperm as a donation to a woman who wanted a baby. The parents interviewed dozens of women for the role, and the child, who is now 3 years old, lives with his biological mother. In 2009, another soldier, who was diagnosed with cancer, donated his sperm for the same purpose. His family also found a surrogate, who is raising the child.

"I represent about 20 families who retrieved sperm from their sons after death and wish to produce a grandchild in some way," says Irit Rosenblum, a lawyer in Tel Aviv. "Until the verdict last month, they thought the most they can achieve is to be 'part grandparents,'" that a biological mother has to be involved. Now I get calls asking me whether they could also use a surrogate mother and raise the grandchild alone."

Rosenblum is not surprised that Israel is the first place to legalize the practice. Having children is considered essential in all cultures, but in this tiny nation that grew out of the ashes of the Holocaust, creating the next generation takes on added significance—with or without technology. Which is perhaps why the country has the highest birth rate in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group of the world's 35 leading economies, and the state subsidizes many in vitro treatments for women well into their 40s. "Adoption is almost nonexistent in Israel," says a professor of gynecology who works in a leading hospital in central Israel and preferred not to be quoted by name. "And there is a strong focus on continuing your own biological line."

The focus is so strong that as the Shahars fought to use Omri's sperm, the government didn't question his purported wish to have children. In fact, most family courts assume a man who didn't leave a will would have wanted kids.

Today, as they start looking for an egg and a surrogate, the Shahars want the Israel Defense Forces to tell families of fallen soldiers that sperm retrieval is an option. "I will never fully recover from my tragedy," Irit says, "but for a moment in court last week, for the first time since Omri died, my heart felt complete again."

As I leave the house with a stack full of Omri refrigerator magnets as mementos, Asher and Irit turn to me and say goodbye. "If it's a boy," they say, "maybe you'll come to the circumcision."