In 2010, a tornado hit Brooklyn, sending rain barreling down for several hours. Someone in Gowanus began recording video of a tide of brown water creeping up the Gowanus Canal. The greenish hue of the pre-storm water is overcome, bit by bit, by the dark, ruddy wave. The videographer gets closer, and someone gags loudly in the background. The water stinks.

"Oh, this is bad. Look at that, a used condom." The gagging person dry-heaves twice.

When it rains in New York City, raw sewage bypasses treatment plants and flows directly into city waterways. Even a relatively small amount of storm water—one-twentieth of an inch of rainfall—can overwhelm New York's aging sewer system and trigger the Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) system, which discharges the rainwater and raw sewage into the many CSO outfalls dotting the edges of the city. CSOs, due to their contribution of fecal coliform, are the single largest source of pathogens to the New York Harbor system, according to the New York Department of Environmental Protection.

Besides the human waste, any oil, industrial waste or household garbage that happens to be on the street when a rainstorm begins are swept by the flowing street water into the CSO system as well. The toxic soup flows untreated out of pipes that feed directly into the waterways.

CSOs are not just a New York problem—sewage in another 771 American cities flows untreated into the waterways when it rains or snows heavily, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In 2002, the EPA estimated the cost of national CSO abatement to be $44.7 billion and called CSOs the "largest category of our nation's wastewater infrastructure that still need to be addressed."

The Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn has it especially bad. Thirteen CSO sites pour 377 million gallons of diluted raw sewage into the canal each year. Drinking the amoeba and bacteria-laden water could give you dysentery or gonorrhea. The sediment at the bottom is packed with cancer-causing compounds and heavy metals. The Gowanus's mere 1.8 miles of dead-end channel constitute one of the most heavily contaminated bodies of water in the United States, and each rainstorm adds to the cesspool.

Just last week, a flash flood in New York City sent a "mysterious brown goo" bubbling out of sinks and toilets at a concert venue in the hip Gowanus neighborhood, where the low-lying sewer system is increasingly overtaxed as more and more residents move in. A 700-unit luxury apartment complex is slated for completion along the edge of the canal in late 2015.

Build It Green, a salvaged building materials retail store, sits at the lowest point on one of the Gowanus streets that run closest to the canal.

"The sewers regularly overflow. Any time there's more than an inch of rain, we regularly have flooding on the street," says Matthew Birnbaum, the store's sales and inventory coordinator. "We had to install a $10,000 flood control system that makes our loading dock inaccessible to trucks."

He worries what the new real estate development will do to the sewer system.

"It is just going to increase the load on the infrastructure. There's going to be more flooding," Birnbaum says. "The fact that they're billing it as waterfront housing is somewhat hilarious."

The real estate company building the development, however, isn't worried. The Lightstone Group says it is building new storm sewers and other infrastructure, worth "millions and millions of dollars in the double digits," to ensure no plumbing or flooding problems, says Ethan Geto, a company spokesman.

"We are convinced that the canal is going to be aesthetic. It is going to be clean. And the smells will be gone," he says.

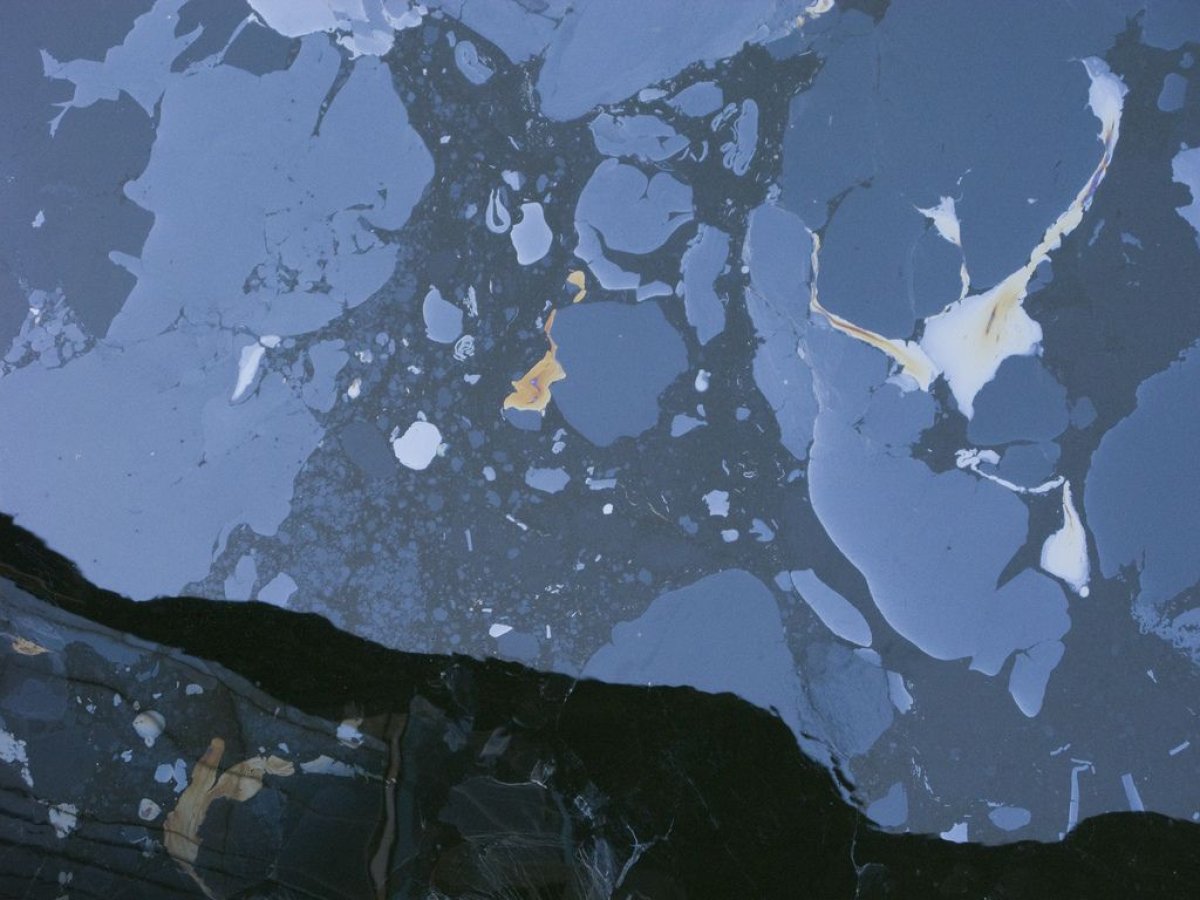

Historically, the banks of the Gowanus Canal were home to chemical plants, gas manufacturing facilities, cement makers, soap makers, tanneries, paint and ink factories and oil refineries, which used the canal for decades as a dumping ground for untreated industrial waste and raw sewage. The concentration of dissolved arsenic in the water is 60 times the level considered damaging to human health, and the canal sediments consist of other heavy metals like lead, iron, manganese, cadmium and zinc, as well as a host of carcinogens. It was declared a federal Superfund site in 2011, and the federal government intends to dredge much of the toxic materials from the bottom of the canal.

The Superfund plan promises to reduce CSOs by 34 percent, but that still leaves around 132 million gallons left per year of CSO sewage to deal with.

The city recently approved a plan for a "Sponge Park," designed to serve as a sort of "constructed marshland" to cope with the weather conditions that create CSOs. Several "bioretention basins" were designed to be planted with plants that can "absorb, accumulate or metabolize pollutants through their roots," and which would be equipped with sand filters to deal with overflow.

The Sponge Park will, its architects hope, reduce contamination in the Gowanus Canal and "provide an evolved urban habitat supporting and promoting estuarine ecology." They acknowledge, however, that this plan will account for only a small portion of the total CSO problem. The plan, if all aspects are implemented, would apply to just 316 acres of the canal's total 1,758-acre watershed, at a cost of $42 million.

Thus far, the design firm dlandstudio has raised $2 million from the city and state, and it plans to begin building a pilot patch of the Sponge Park on one Gowanus block later this year. It may not be much, but if the plan works, it could be the next step for hundreds of U.S. cities that spew their own poo every time a rainstorm hits.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zoë is a senior writer at Newsweek. She covers science, the environment, and human health. She has written for a ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.