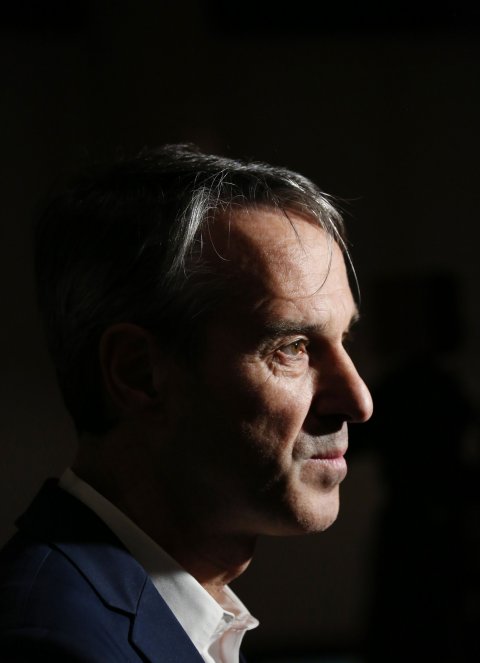

Ivo van Hove was 8 when death first marked him. His mother took him on a 90-minute bus ride from their rural Belgian village to Antwerp, where Bambi was playing in the movie theater. On screen, Bambi's mother died at the hands of a hunter; van Hove's course was set. "I cried all the way home," he says, sitting with his hands clasped, on one side of a long, bare table in the white-walled, high-ceilinged meeting room of the Stadsschouwburg theater in Amsterdam. "I discovered then what art can do with you."

Or, perhaps, what he can do with art. Van Hove is one of the world's most sought-after theater directors. He's been well-known across mainland Europe since 1987, when Belgian radio declared his version of Frank Wedekind's Lulu the production of the year, but in the past two years he's moved swiftly and decisively into the mainstream. His visceral, stripped-to-the-bone version of Arthur Miller's A View From the Bridge, commissioned by the Young Vic in London in 2014, transferred first to the West End and then to Broadway, where it won two Tonys, including the award for best director. It was followed in November 2015 by the New York premiere of Lazarus, David Bowie's musical sequel to the 1963 book and 1976 movie The Man Who Fell to Earth, and, a few months after that, by another van Hove rethinking of Miller, this time The Crucible. For a moment there, the Great White Way might have been renamed Van Hove Avenue.

Van Hove's artistic home, though, is Amsterdam, where he runs Toneelgroep, Holland's leading theater company, and in whose offices we meet on a hot August afternoon. A poised, contained man of 57 with fine-boned, hawkish good looks, he speaks quickly but softly; you have to concentrate to hear him. He wears jeans and an open-necked, blue and white-striped shirt, but there is nothing casual about him.

He is in the first week of rehearsals for The Things That Pass, which will premiere September 16 at the Ruhrtriennale arts festival in western Germany. It is an adaptation of a short, elliptical and—considering it was published in 1906—startlingly postmodern novel by the Dutch author Louis Couperus. Why Couperus, and why this Couperus?

"I consider him an author of the level of Wilde, Proust, Thomas Mann," says van Hove. "If Couperus had written in English or French, he would have been world-famous by now. He's so good at putting big questions on the table. Couperus writes about fear and the family, about how repression leads to destruction, and about mortality, how difficult it is for us to deal with death. In my plays, death is one of the things that returns."

It would be hard to avoid in this particular piece: At its center are two very old former lovers, both of them waiting to die, both believing that nobody knows about the horrible murder they committed 60 years before. But the truth of their crime infects the whole of an extended family, including two grandchildren who, not knowing they are related, are about to marry. How, I ask, will van Hove—who at Toneelgroep tends to work with the same close-knit ensemble of actors—deal with a cast of characters that is both large and largely very old?

"Sometimes in a little boy you see already the old man, and sometimes in the old man you see still the little boy," he says. "So I'm not dealing with it in a realistic way. The set has no doors, the cast enters into an open space almost like a waiting room, they are stuck there. It's not naturalistic. A person who is 75 can behave like somebody of 20; it will switch all the time. We're trying to make a very theatrical production."

What van Hove means by theatrical is something very specific. Perhaps the best way to define it is as maximalist minimalism: a way of telling a story that avoids dwelling on its surface, instead focusing, almost to the point of obsession, on its core truths. His rendering of A View From the Bridge threw out all the props and domestic trappings of Miller's dockside setting, instead pitting his characters against each other in a bare, enclosed square that was part classical amphitheater, part boxing ring. It ended with a frozen tableau of the cast coiled around each other, wrestling and drenched in blood that poured from the ceiling, a living, panting icon of the violence that beats at the heart of the play.

As any cook can tell you, boiling something down to its essence takes time. Before he starts rehearsals, van Hove spends months analyzing a text, mining for images that he and his lifelong partner and set designer, Jan Versweyveld, can "turn into a world. For instance, after David Bowie read Lazarus to me, David asked, 'What do you think?' I said, 'It feels to me as if everything is happening within his skull, that we are in his mind.' And that simple image is the set."

The design is the screen saver on Van Hove's laptop; he shows it to me. An empty apartment, lit blood red, with two square windows at the rear, and an oblong video screen standing upright between them: It is a skull. "But nobody yet has spotted that!" van Hove says, beaming.

In rehearsal, he says, "I know where I'm going, and the important points on the way, and I know where will I give in. For instance, today I talked for half the rehearsal, because I had to poison the actors with my thoughts." Van Hove gives his poison in individual doses, whispering performance notes into his actors' ears.

Sometimes he does more than whisper. Luke Norris, who played Rodolpho in A View From the Bridge, says, "I remember him pushing me, physically pushing me in one scene and saying, 'More, more, this is his whole existence, right now,' which resulted in me screaming and fighting for my life in a scene where before, I had been trying to charm and bargain my way to a result. Once I'd done that, he just smiled and said, 'That's it.'" What "it" is, van Hove says, "is theater that gives the audience the most unique experience; don't go for the middle of the road, make it personal, and as extreme as you can think of."

He calls this method "X-raying the text." British playwright Simon Stephens is one of only a handful of living writers to have been on the receiving end of those rays. It's an analogy he thinks could hardly be more apt. "An X-ray shows a profound truth of your body—but you might not recognize yourself. In my play Song From Far Away [in which a man recites a series of six letters he's written to his dead brother], there was a question in the script that I hadn't answered: 'Who is the actor talking to?'"

Stumped by this, the Dutch actor playing the role was struggling to find a way in—until van Hove got up and put an empty chair in front of him. It was that same transformation as in A View From the Bridge, an idea leaving the realm of the abstract and becoming physical. "I hadn't seen it in the writing, but Ivo saw," Stephens says. "An empty chair, a place with the body taken away. What better way to dramatize grief?"

Which brings us back to death. Van Hove's relationship with it seems to be the wellspring of both his technical rigor and his acute emotional empathy (on the interview tape, he begins, very subtly, to mirror my intonations). When he says, "I have always been in touch with death," he's talking about more than Bambi. At boarding school, aged 16, he fell in love with a fellow pupil: "I don't know if he was in love with me, whatever—nothing happened, or it almost happened but not really anything—and then suddenly he wasn't there anymore." The boy had been killed in a road accident; van Hove says he spent a year mourning. "But I couldn't talk with anybody about that loss. I think when you're mourning, you're always alone." In a theater, though, you have a whole auditorium to talk to.

Did losing Bowie, after working closely with him during the final months of his life, teach him anything about how to deal with death? "I really don't know yet. It's only like six, seven months, and I've been working all the time, and I feel that it's for me a deeper experience than I thought it would be. But I am aware more than ever that every production should be meaningful…that every second is a second and you shouldn't spoil it on shit."

Lazarus will be showing in London this October, and "David will be there. He will be there." In the meantime, there is Couperus's exploration of mortality to deal with, and a commitment to turn Luchino Visconti's 1942 murderous film noir, Obsession, into a play at London's Barbican Centre, with Jude Law in the lead. Neither productions are likely to be comedies, but audiences can expect to see the bones of both. As Stephens says, "An X-ray machine might seem like a dehumanizing metaphor for Ivo, but actually it's exactly right. Because its function is to make us understand ourselves more deeply. And to make us better."

FACT BOX:

The Things That Pass: Zeche Zweckel, Gladbeck, Germany, September 16-24, then touring; Lazarus, King's Cross Theatre, London, from October 25; Kings of War, Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York, November 3-6, then touring; Song From Far Away, Frascati, Amsterdam, November 15-19; Roman Tragedies, Barbican, London, March 17-19, 2017; Obsession, Barbican, London, from April 19, 2017, then touring; www.tga.nl