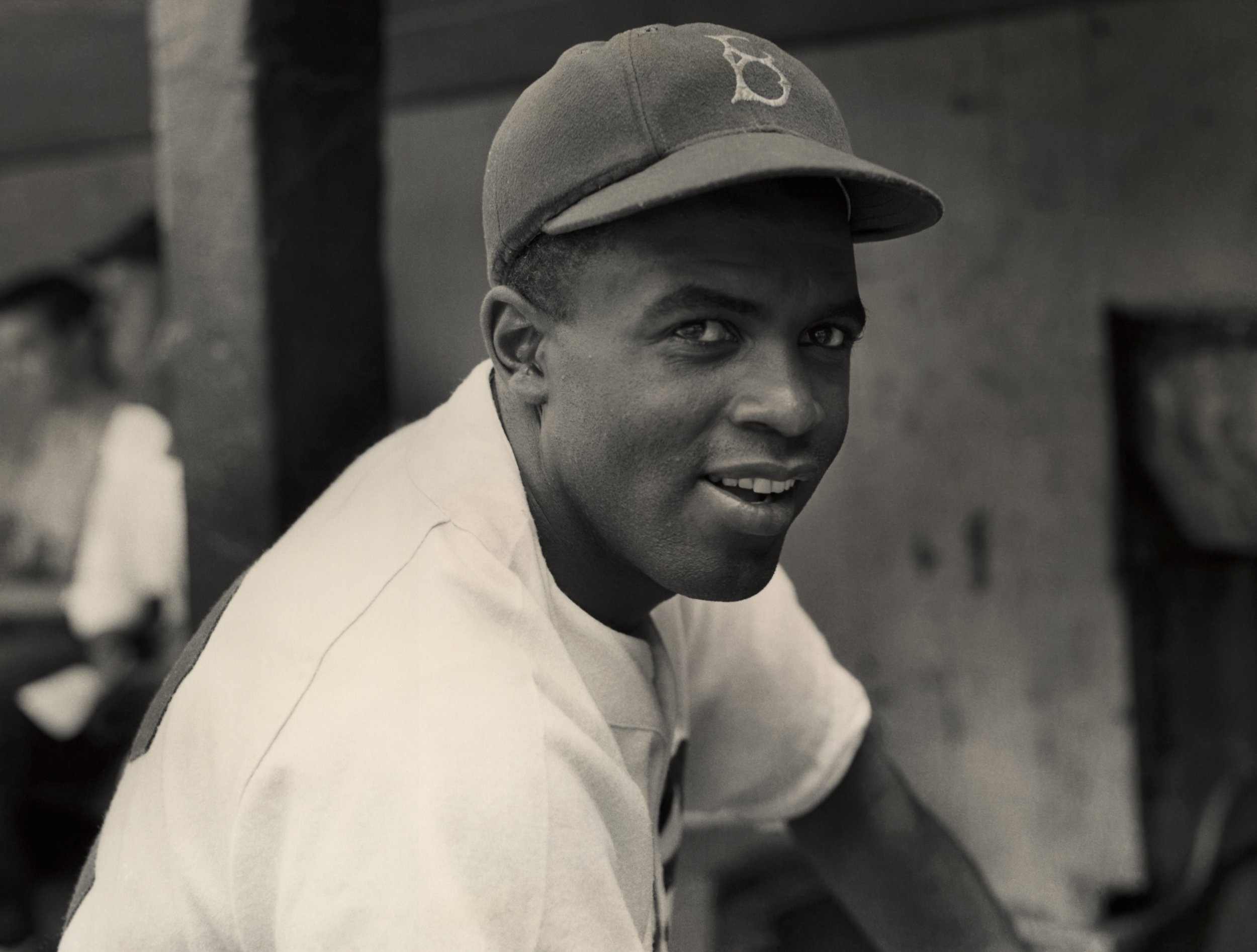

On Monday night, PBS premiered the first two hours of Ken Burns's latest documentary, Jackie Robinson. The film takes a look at the life of one of the 20th century's most misunderstood icons. Since breaking Major League Baseball's color barrier in 1947, Robinson has been mythologized to such an extreme degree that history has lost sight of the greater scope of his impact. He was not content to turn the other cheek; he was angry, never satisfied and continued working tirelessly for equal rights long after his playing days were over.

In March, we spoke to Burns about race in contemporary America, the legacy of the civil rights movement and what we can learn from Jackie Robinson. Now that the first part of the documentary has aired (the second airs Tuesday night on PBS), here are 9 things we learned about Robinson from Burns's stunning portrait, which he co-produced with his daughter Sarah and her husband, David McMahon.

1. He Could Have Not Only Gone Pro, But Been an All-Time Great in Any Sport

Robinson was a four-sport letter winner at UCLA, and the degree to which he stood out in each sport he played—track and field, baseball, basketball and football—was astonishing. He was such a gifted athlete that before he decided to go to school in Pasadena, California, where his family moved from his hometown of Cairo, Georgia, an alumnus of Stanford offered to pay his tuition if he would simply go to a school that wouldn't play Stanford. Once enrolled at UCLA, he shined the brightest on the football field. The press started calling him simply "Jackie." Says writer Howard Bryant, "You could make an argument that Jackie Robinson was the greatest athlete in American history."

2. He Refused to Move to the Back of the Bus 11 Years Before Rosa Parks

When Robinson was in the military in 1944, he boarded a bus headed to Temple, Texas, from Fort Hood, where he was stationed. He was asked to move to the back of the bus, but refused. He knew that regulations had recently been sent out that called for no discrimination on military vehicles. The bus driver demanded his identification, and a white woman threatened to press charges. He told the bus driver, "Quit fucking with me." The military police arrived, and after Robinson refused to cooperate, he was arrested.

"Think about the number of black men, in 1944, who challenged authority in such a bold way," says writer Howard Bryant. "Not just refusing to give up his seat, not just refusing to do what he was told, but to actively stand up and swear at them."

3. Robinson's Iconic Embrace With Pee Wee Reese Probably Never Happened

Outside of the Brooklyn Cyclones' home field in Coney Island, there is a statue of Robinson and Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese with his arm around his second baseman. The monument commemorates when, in 1947, Reese made a point to publicly embrace his new teammate in Cincinnati, just after he had broken the color barrier. The only problem is that this moment probably never happened. There was no mention of it in the press and no one can seem to confirm it. When Robinson's wife, Rachel, heard of the plans to erect a statue, she insisted they use another moment between the two, to no avail. "White people want some skin the game," Ken Burns told Newsweek when speaking about how the moment has been mythologized. "No pun intended."

4. Robinson Couldn't Have Done it Without His Wife, Rachel

Rachel Robinson was the driving force behind the documentary's production, pressing Burns to do something fleshing out the story of her late husband. Throughout Robinson's playing career, Rachel was his confidant, his rock and his only refuge from the incessant abuse he endured. Burns is able to highlight the importance of the college sweethearts' relationship through an interview with Barack and Michelle Obama, whose journey has been not unlike that of Jackie and Rachel's. "Jackie is the first to go through a door back then, and he clearly could not have done it without Rachel," Burns told Newsweek. "The president is the first to go through a door, and he's saying [in the documentary] that when people are giving you shit for stuff that has to do with the color of your skin, it's good to go home to where people love you and have your back."

5. After Retiring, He Took a Job as an Executive at Chock Full O' Nuts

In March of 1957, Robinson began working full-time for Chock Full O' Nuts. He felt that once his career in the Major Leagues was over, so was his involvement in baseball. He was always looking ahead and fighting the battles that were in front of him, not behind him. When he was asked to throw out the first pitch in Game 2 of the 1972 World Series, he agreed only under the condition that he would be able to use the opportunity to speak his mind. He never felt he was indebted to baseball. "You never steal the base that you left," says his friend Marty Edelman. "You steal the next base."

6. He Supported Politicians Based on What They Could do For Black Americans

Robinson believed in having a fluid approach to politics, and that black Americans shouldn't vote for any party in particular, only which candidate could do the most for the black community. In 1960, he campaigned full time for Republican Richard Nixon, believing that John F. Kennedy was soft on civil rights. Robinson even refused to take a picture with Kennedy after the Massachusetts senator met with a segregationist governor. When Kennedy chose Lyndon B. Johnson as his running mate, Robinson called it a move for the "appeasement of Southern bigots."

But when Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested and jailed weeks before the election, Nixon refused to help, and Robinson quickly disavowed him. Kennedy, on the other hand, placed a call to King's wife, and his brother, Bobby, talked the judge into releasing the civil rights leader. The move curried favor for Kennedy within the black community, and he won the election by 100,000 votes.

7. He Was the First Nationally Syndicated Black Writer

In 1959, Robinson began writing a weekly column for the New York Post. The column was syndicated, and though it appeared in the sports section, it touched on broader social issues. "Whites just assumed that blacks had the same perspectives that they had," says William Branch, who co-wrote the column with Robinson (although it appeared under Robinson's byline). "The column made a great contribution in informing whites in particular of attitudes and events and perspectives from the black community."

Robinson continued to write, later contributing to the Amsterdam News in Harlem, where he denounced Malcolm X's militancy. Though Robinson "turned the other cheek" with reluctance during his playing days, he believed strongly that violence was not the answer.

8. He Helped Found a Bank That Helped Black Americans

Robinson felt that economic development was crucial to the advancement of black people in America. In 1964, he helped found Freedom National Bank in Harlem. Just as it was difficult for the Robinsons to find landlords who would rent to them in his early playing days, it was difficult for black Americans to secure loans or mortgages. Freedom National provided people of color with a means to develop themselves financially. "We're only hoping we can get the same kind of support here that we did in Ebbets Field," Robinson said in an interview after Freedom National opened a branch in Brooklyn. Three years later, it would be the most successful black-run bank in the country.

9. His Hall of Fame Plaque Doesn't Mention That He's Black

There's no doubt Robinson was a Hall of Fame-caliber player, but there is also no doubt that his greatest contribution to the game has nothing to do with box scores. When he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1962, his plaque contained no mention that he was the first African-American player in the Major Leagues. This wasn't totally surprising. When Robinson played his first Major League game in 1947, one of—if not the—most important events in the history of baseball, the newspapers made little mention of the color barrier being broken.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ryan Bort is a staff writer covering culture for Newsweek. Previously, he was a freelance writer and editor, and his ... Read more