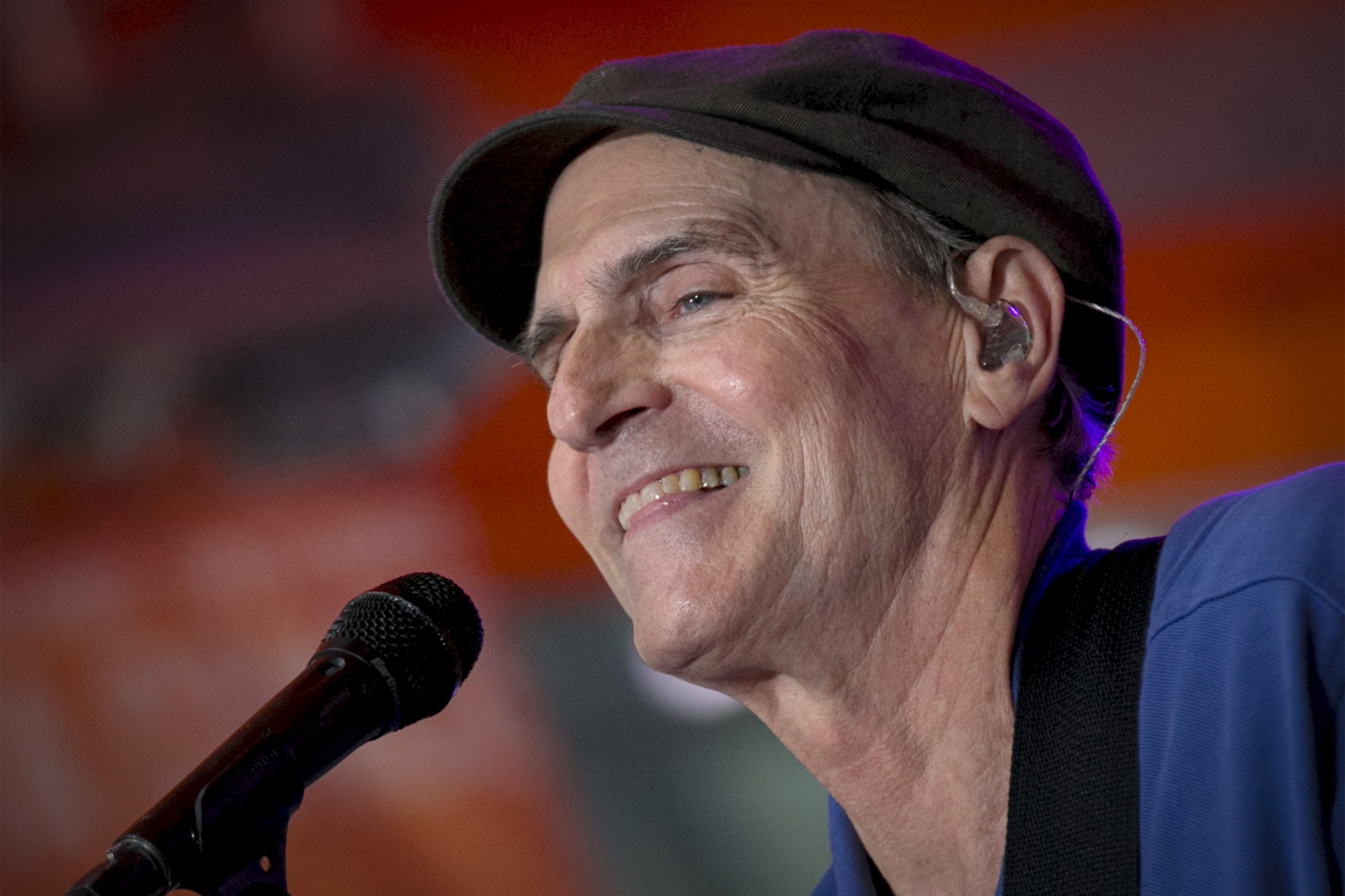

This is an exclusive excerpt from Sweet Dreams and Flying Machines: The Life and Music of James Taylor, by Mark Ribowsky. This chapter covers the folk singer's rise to fame in the early 1970s, when he released his album Sweet Baby James.

In the run-up to Sweet Baby James's release, Warner Brothers sent promotional materials to newspapers and magazines about James Taylor, and they were not at all reticent to play up his history as something less than a Boy Scout, wanting to help create some buzz about the genesis of his songs. One part of the release, with Taylor relating his past, read: "In the fall 1965 I entered a state of what must have been intense adolescence...and spent nine months of voluntary commitment at McLean Psychiatric Hospital in Massachusetts." However, thinking better of it, Warner deleted that sentence from the materials—of course, too late for it not to get around, or for Taylor himself to have related the same details in brutal detail, a practice he would only continue. And when they agreed on a title for the work, rather than the obvious grabber of Fire and Rain, it was the much more winsome Sweet Baby James, the title track of which would be preferable to the third-rail images of "Fire and Rain."

Issued just after the New Year, a month ahead of the planned album release, "Sweet Baby James," as beautiful a song as has ever been recorded, died in a sea of apathy. The album then hit the market, a Henry Diltz photo of a clean-shaven, almost preppy-looking Taylor in his usual pissed-off pose on the cover. The first reviews hit in early spring, with Rolling Stone's Gary Von Tersch hearing the influences of the Band, the Byrds, "country Dylan, and folksified Dion," yet avowing that Taylor "pulls through it all with a very listenable record that is all his own" with arrangements "gentle" and "intelligent"—even if Von Tersch misheard one of the indelible lyrics as "sweet dreams and fire machines." He averred: "Taylor's persistent lonely prairie/lovely Heaven visions work their way up to the intensity of a haiku or the complexity of a parable.... Taylor seems to have found the ideal musical vehicle to say what he has to say."

Ben Edmonds, in Fusion magazine, confessed:

I must admit that [the album] took me nearly by surprise. Taylor's work has a marvelous capacity for growth, a time-release quality, so much so that upon the arrival of this album I was still very much captivated by the Apple disc. If he had never produced another thing, I am of the opinion that his first release would go on sustaining itself (and me) forever. But the new album is here and it serves to reinforce the picture of Taylor we got from his initial effort. His songs present a vivid portrait of the man. Indeed, no division between the two can be made. . . . James Taylor is a permanent resident in my home. Yours too, I hope.

Sales moved slowly but were enough for Warner to cut bait on "Sweet Baby James" and rush out "Fire and Rain," backed with "Anywhere Like Heaven." The first time Taylor played "Fire and Rain" and "Sweet Baby James" together in concert was on February 6, 1970, at the Jabberwocky Cafe at Syracuse University, setting in motion Asher's plan for building up a college market for Taylor. There, alone on a stool, he played a 28-song marathon that also included some of the Apple stuff, covers of the Beatles ("Yesterday," "If I Needed Someone"), Woody Guthrie ("Pretty Boy Floyd"), Wilmer Watts ("Duncan and Brady"), the Impressions ("People Get Ready"), the Carter Family ("Diamond in the Rough"), Ray Charles ("Hallelujah I Love Her So") and goofs like the "Things Go Better with Coke" jingle, a smug reference to cocaine. Next up would be Worcester State College, Sanders Theater in Cambridge, and Berkeley University Community Theater. And each show would gain him more of a foothold.

At the time, and now all but forgotten, another Taylor-style folk prodigy, who had also come of age in the coffeehouses of Boston, Norman Greenbaum, late of Dr. West's Medicine Show and Junk Band, was on the same upward path with his "gospel-rock" send-up of religious hucksters, "Spirit in the Sky," which would sell two million copies and also go to number 3, in April. Going step for step with Creedence's "Green River," the Guess Who's "American Woman," Crosby, Stills and Nash's "Woodstock" and the execrable bubblegum studio concoction "Sugar Sugar" as the freshest flavor of the day, Greenbaum seemed poised for a breakout as a troubadour, and would release a number of fine folk-soft-rock songs such as "Canned Ham" and "Dairy Queen"—the last in particular sounding indistinguishable from Taylor. But then, out of nowhere, "Fire and Rain" finally caught hold. Taylor, touring tirelessly—heroin helped—got more buzz over the summer when he played the Mariposa Folk Festival in Ontario, Canada, a slice of the market pie Asher did not overlook—though when he bluffed the promoters by saying he wanted $20,000 for Taylor, he wound up settling for 78 bucks.

By late September, with airplay getting heavy for "Fire and Rain," a cover of the tune with banjos and brass was issued by Johnny Rivers (who replaced "Suzanne" with "girl"), quite a coup in itself for Taylor, and it too was on the charts, though it would be left in the dust at number 94 once the original took off, not stopping to gain until, with Sweet Baby James in its 31st week on the list and still at number 5, the record hit number 3 on October 31, behind the Jackson 5's "I'll Be There" and the Carpenters' really soft rock sedative "We've Only Just Begun," and just ahead of Neil Diamond's "Cracklin' Rosie" and Sugarloaf's "Green-Eyed Lady." It was apt that "Fire and Rain," harrowing in content as it was, reached its apogee on Halloween. By then the song had risen as well to number 7 on the easy listening (later adult contemporary) list. It did even better in Canada, where it went to number 2, and also charted in England and the Netherlands. Sweet Baby James, meanwhile, peaked at the same number 3 on the album chart in the United States and Canada, number 6 in England.

Robert Hilburn attaches all sorts of profound significance to the burgeoning sales of the record. "The rock and roll generation was almost exhausted from the '60s and wanted to calm down. And 'Fire and Rain' was a perfect song for that. Enough of the drugs, enough of the war, they just wanted to regroup. The '60s had lost steam, rock and roll needed to take a breath. And that's when the singer/songwriter movement was at its most powerful." No small wonder that the dulcet refrains of Sweet Baby James were heard so much, particularly through the nooks and crannies of the place where it was made, where the forces had pointed it to be made. Like no other before it, said Barney Hoskyns, "Sweet Baby James became the sound of the Canyon."

Not really able to figure out why himself, James Taylor suddenly found himself in demand all over the rock topography; concert invitations poured in from at home and abroad, especially England, where Allen Klein rereleased "Carolina in My Mind," which had a second-chance run up the chart, to number 67 in the United States. However, for Taylor and Asher, it was hard to take a victory lap. They suspected some funny business was going on that undercut the singles that spun off the work. The first, the title track, did nothing, not smelling the chart. Yet "Fire and Rain," which carried the album, was heard everywhere, getting loads of airplay on both Top 40 and the album-oriented FM stations. In December, it was licensed by producers for the soundtrack of the NBC television show Bracken's World. Maybe it was because those who bought the record played it so much—"Endlessly," says Danny Kortchmar, "wherever I'd go someone had that damn song on a turntable"—in group situations, and especially in college dorms, as long as someone owned it, others didn't need to.

But stopping short of number 1 seemed baffling, even for the inexact science of record charting, which is based on any number of arcane criteria. What's more, the official status of "Fire and Rain" is still in doubt. It would be ingrained in the loam of music forever—for what it's worth, number 227 on Rolling Stone 's 2011 list of the 500 greatest songs of all time—and sell one-and-a-half-million copies in 1970 (over three million to date—reflecting the new paradigm, in 2013 it was decided that one hundred audio streams on the Internet equaled one unit sold). Sweet Baby James would stay on the chart for two years and be certified gold in October 1970 (the Recording Industry Association of America would revise downward the gold-level standard in 1981 to 500,000); for reasons unexplained, the RIAA has not to this day given "Fire and Rain" gold record certification, surely a glitch in the system.

Or is it? As Liz Kennedy, communications director of the RIAA, explains, "The RIAA itself does not track music sales by artist, title, or genre, but we can offer certifications when the label or artist has requested certification after certain U.S. sales thresholds have been met. Since RIAA awards are only certified upon request, it's not up to us!" If the explanation is that simple, it means that—amazingly, and for whatever reason—neither Taylor nor Asher nor anyone at Warner Brothers has ever requested gold status for "Fire and Rain." As Kennedy laughs, it's about time someone got on the phone and made that call. Still, Taylor did earn a Grammy nomination for Best Album—losing to Simon and Garfunkel's Bridge over Troubled Water—and four others, for Contemporary Male Vocalist, Contemporary Song, Record of the Year, and Song of the Year, and only Ray Stevens and Miles Davis had that many nominations.

However, he did not win any. Sitting in the audience in his rented tux at the drafty Hollywood Palladium with Joni Mitchell, glowering all the while, his contempt for the tawdry self-congratulatory rituals of awards like these was set into cement; even decades later, as the winner of a brace of Grammys, he would say, "I have a love-hate relationship with the Grammys because I don't see the music world as a competitive sport." It was a relationship he would need to get very accustomed to.

Yet the shutout of Sweet Baby James did not sit well. If there was any comfort, it was that the album had put him in the fast lane, in a new stratum, one that would leave James Taylor in a position that he could not have imagined a year ago. Along with Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills and Nash, he was a team leader as L.A. soft rock charged hard into the 1970s.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.