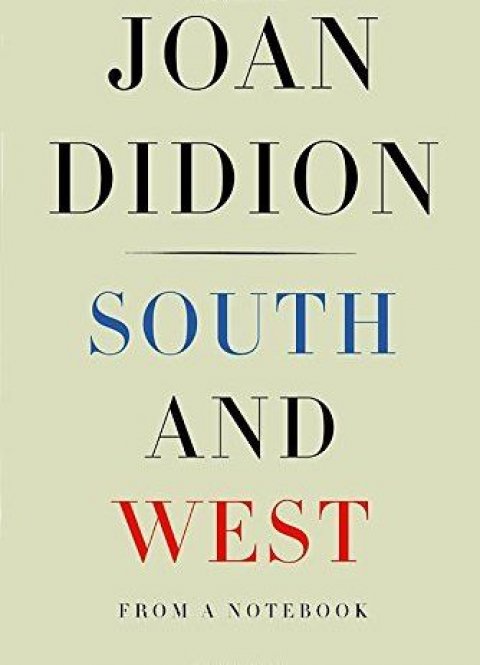

The prose of Joan Didion is a kind of fog, rendering everything opalescent with fresh, weird light. It's the world you know, except not quite. Her idiosyncratic genius is in full evidence in South and West, a slim new volume that collects two fragments that never quite turned into published essays. Ideas and images come into quick relief: the "morbid luminescence" of New Orleans, the entire notion of California summoned up with unteachable prose: "Rattlers in the dry grass. Sharks beneath the Golden Gate."

The first fragment in South and West, and by far the more substantial of the two, is the record of a journey the Sacramento native took across the American South in 1970, with her husband, John Gregory Dunne, late of Connecticut. The essay begins in New Orleans, a city gothic and baroque, the very opposite of the Los Angeles where Didion and Dunne then lived. Whereas Los Angeles is all surfaces, New Orleans is all depths. "In New Orleans in June the air is heavy with sex and death, not violent death but death by decay, overripeness, rotting, death by drowning, suffocation, fever of unknown etiology," Didion says in the essay's first sentence. She had briefly lived in Durham, North Carolina, as a child in the 1940s. Returning there as an adult, she finds constant occasion for dread: "Bananas would rot, and harbor tarantulas. Weather would come in on the radar, and be bad."

RELATED: How the 'Green Book' saved black lives on the road

From there, Didion and Dunne head into the deeper South of Mississippi and Alabama. If it is today fashionable to parachute into northern Ohio for frontline reportage on the white working class, the rural South was the place you visited to understand what America had become in the age of Nixon. Only a few years before, California had been the center of both the culture and counterculture, and Didion had been there to chronicle it, hanging out with the Doors ("the Norman Mailers of the Top Forty") on Sunset Boulevard, buying a dress for Charles Manson associate Linda Kasabian in Beverly Hills. But in the new decade, California's relevance seemed to diminish.

Didion, who always wanted to matter, is plainly jealous in South and West that the South matters more than her native state: "For some years the South and particularly the Gulf Coast had been for America what people were still saying California was, and what California seemed to me not to be: the future, the secret source of malevolent and benevolent energy, the psychic center." As she leaves New Orleans, those malevolent energies in particular become more evident: a beach towel she buys in Mississippi emblazoned with the Confederate flag, a "demented afternoon" in Meridian, a man standing on Main Street shooting pigeons with a shotgun.

At the Mississippi Broadcasters' Convention, Didion marvels at a phenomenon that seems the precursor of today's "fake news": "The isolation of these people from the currents of American life in 1970 was startling and bewildering to behold. All their information was fifth-hand, and mythicized in the handing down." She has lunch with one of the attendees, Stan Torgerson of WQIC, who tells her about a "black druggist" who went north and came back South, apparently missing home. "We're not nearly as inbred as we used to be," Torgerson confidently tells Didion.

The second fragment in South and West is both shorter and less satisfying. In 1976, Didion went to San Francisco to cover the trial of Patty Hearst—the complicit, bank-robbing "captive" of the Symbionese Liberation Army—for Rolling Stone. "I thought the trial had some meaning for me—because I was from California," she writes in a short introductory note. "This didn't turn out to be true." This is also a disappointment for readers who might long for Didion to build some fantastic bridge between herself and the newspaper heiress turned leftist revolutionary. It is a reminder, as well, that while Didion was a first-rate observer, she was not a natural reporter.

The insanity of the Hearst episode, its utter lack of context within history and culture, fostered in Didion a sense of longing for the kind of epic struggles she had witnessed six years before: "In the South they are convinced that they are capable of having bloodied their land with history. In the West we lack this conviction." I imagine that Jann Wenner, the Rolling Stone founder, wanted this and more from the Hearst essay. But Didion had the intellectual honesty to say she couldn't deliver. Thus this fragment, its beauties tantalizingly minute.

Here, and elsewhere, Didion seemed to be aware that she was recording a singular moment in the culture. "I am trying to place myself in history," she writes in the Hearst essay. She did not want to transcend the madness of the day, escape it, but rather to capture it completely.