BROOKLYN, NY - The drama unfolding on the eighth floor of Brooklyn's federal court on Thursday could easily be mistaken for an epic telenovela episode.

There was the reputed drug cartel leader Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán Loera clad in a smart charcoal suit facing down a former Colombian drug smuggling cohort testifying against him through multiple interpreters to extend the Q&A, his 29-year-old former beauty queen wife and mother of his twin 7-year-old daughters returning waves and gazing grins from the second row of benches which has a paper sign that reads: "DEFENSE." And three trollies wheeled in full of evidence files as well as a display of multimedia, including: surveillance videos, telephone recordings -- and even a cameo involving the unpacking of two DEA-marked boxes worth of Heroin bricks.

Guzmán, 61, was routinely referred to by the more flamboyant title: "Don Joaquín Guzmán Loera" or "Don Joaquín" is facing a raft of federal conspiracy and drug trafficking charges for a decades-long reign atop the $14 billion drug empire the Sinaloa cartel. The government has brought in a series of witnesses that have already testified that the Chapo masterminded a logistical enterprise and moved massive tons of dope into the U.S. and also savagely flexed his power with having a hand in more than 30 murders.

Enter Jorge Milton Cifuentes-Villa.

The 52-year-old bespectacled man from Medellín is an admitted drug lord from a long lineage of family traffickers -- he and most of his eight siblings and parents all kept their beaks wet with the cocaine business, according to his testimony.

As a career criminal, Cifuentes, with a kind of casual bluntness talked about the hustle and bustle of bringing in product over the U.S. border.

But there were bad days at the office.

For instance, while being questioned by Assistant U.S. Attorney Adam Fels about a particular deal involving Chapo and the FARC Colombian guerillas, Cifuentes broke down how the cartel brazenly greased Ecuadorian government officials with "Don Joaquín's money" to ship the pure product to a Guayaquil-based warehouse.

As far as FARC, Chapo apparently was aiming to secure 6 tons of cocaine.

It would be a tall order because of the fact that the Sinaloa Cartel's security measures were on the fritz.

The cartel at the time lost its Canadian-based cryptography system because of snafu involving one of their engineer's failure to pay a bill rendering their Blackberrys and communications, like calls and text messages, vulnerable and picked-up by law enforcement officers.

In one of the recorded telephone calls played in court, their forcefield was clearly down.

"The system is down now so none of us can have secure communications anywhere, Cifuentes told the prosecutor, interpreting the May 21 phone call.

When asked to explain why "extensions" weren't working, Cifuentes said that "they were talking about the encryption communication system wasn't working because the engineer didn't pay for the licenses."

More phone call recordings were played before the courtroom; some of them were identified as El Chapo and a FARC member.

In this particular deal, Cifuentes claims that he had to put up millions of dollars worth of real estate at the behest of Guzmán to broker 8 tons of FARC coke. "Don Joaquín Guzmán Loera placed my properties as collateral," he said. "He asked me to get the money for the cocaine for the next trip."

He initially compiled and assured he could procure 3 tons of cocaine.

But then Guzmán wanted to send his nephew to survey the goods. And showing some moxie of his own, Cifuentes claims he faced down the big boss.

"I told him 'No things are not going the way you might want them to go.'"

But Cifuentes beckoned because he claims he was concerned about his the well-being of one of his kin.

"I feared for my brother's safety," he said.

Eventually, Cifuentes was shown a surveillance video clip featuring his accountant with two other men who were convening to discuss the value of his real estate holdings.

Soon after, Guzmán was pleased with the properties he'd offered up to sweeten the deal.

Using his plush properties as collateral and some of Don Joaquín's cash, the FARC rebel on the phone attempted to barter.

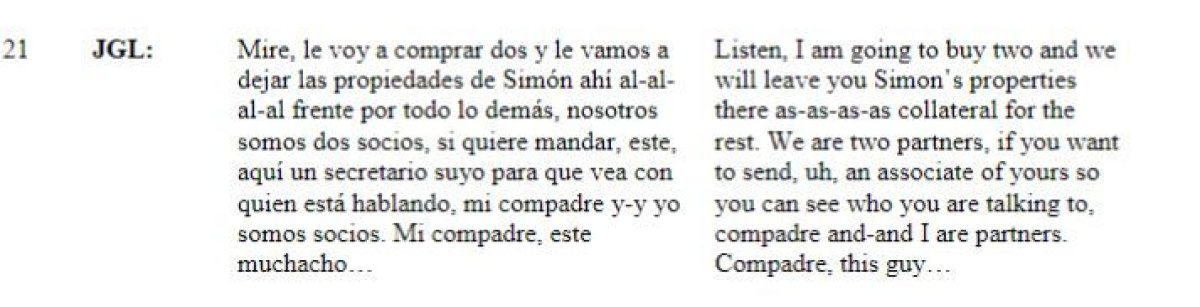

During the conversation between Guzmán and the FARC rebel, the cartel boss shrewdly made the rebel blink; whittling down the price for the cocaine by offering cash, the properties and credit.

At first, the rebel wanted 2.5 tons to be paid out in cash.

But Guzmán, told him on the recorded call, "Listen, I'm going to buy 2 and leave Simon's [a nickname for Cifuentes] property to pay for the rest."

Cifuentes saluted Guzmán's wizardry as a dealmaker.

"First of all he's a very good businessman," he said, to chuckles in the courtroom. "He's saying he doing to pay for 2 [in cash] and not 2.5," he said.

All the risk-taking proved fatal since the deal fell through and authorities had the top boss on the phone allegedly trying to move tons of cocaine.

The prisoner was asked about the reasons he was cooperating with the government.

He testified that he hoped that by telling the truth and opening the kimono to some of the inner workings of the Sinaloa Cartel that he might win favor to one day be reunited with his family and perhaps not rot in a prison cell.

"I'm hoping to get a sentence reduced," he said through the interpreter. "I'm 53-years-old so a life sentence means life to me."

Guzmán's attorney, Jeffrey Lichtman, who years back managed to help notorious mob boss son John Gotti Jr. beat racketeering charges over a decade ago, attempted to poke holes in the witness.

But before he did, a Drug Enforcement Agency investigator took the stand and out came a spectacular stack of 18 heroin bricks, pulled out by black-gloved hands of a plain-dressed security officer and laid bare on the prosecutor's table for several minutes.

They tested to be 94.4% pure and with black marker on each of them was the Spanish word, "BOTE" -- which translates in English to "boat," the investigator said.

The plastic sealed 19.74 kilos were confiscated during a 2008 drug deal outside a Home Depot in North Lake, Illinois.

The cross-examination showed Cifuentes as a corrupted convict who joined a his family members to traffic drugs, had sex with a jail guard's wife, committed attempted murder, faked his bona fides by buying diplomas from both Colombian, Mexican and even a Texas university (he denied this), and deceived the government.

He also had a way of keeping a shady trail.

That was due in large part to the dizzying number of aliases Cifuentes admitted to adopting when attempting to duck the law while wandering the globe and buying multi-million homes in Texas and Florida. He went by names like, "Elkon Lopez", "Jose Luiz Garcia Ramirez", "Santiago Gonzalez", and "Sergio Asuna".

Cifuentes acknowledged he had been helping the government since 2014 and vowed he had been truthful, even admitting he "committed crimes in the U.S."

His father drove a truck that initially moved whiskey and cigarette contraband, he explained. But then graduated to drugs.

Lichtman attempted to prove that Cifuentes withheld information from law enforcement about his family members' involvement as narco-traffickers.

"You never mentioned [your father] was a dealer," Lichtman said.

"You're mistaken, sir. I didn't do that," Cifuentes responded.

In the end, Cifuentes admitted that his father and many of his siblings and a nephew either helped dry and process cocaine on the family's Colombian farm, and that some caught cases and served prison sentences.

In one particularly awkward exchange, Lichtman presses Cifuentes to admit his family wasn't a typical one.

The attorney asked if Cifuentes considered his family "close."

He responded "Unfortunately, no. We had conflicts like any normal family could have. Gossip here. Gossip there."

"Like the time you brother Alex ordered the murder of your nephew Jaime," Lichtman said with a thick layer of sarcasm.

"Yes, sir," Cifuentes said.

"Typical family issues," Lichtman again pried. "Jaime ordered the kidnapping of his grandmother."

Again, Cifuentes agreed.

The attorney almost couldn't help himself, again exclaiming: "Typical family issues!"

At this point the prosecutor Fels objected.

After Lichtman confronted Cifuentes for taking a jaunt to Switzerland and purchasing three Rolex watches with a credit card that included one of his many pseudonyms, the inmate didn't seem to see the wrongdoing.

When accused of committing fraud, Cifuentes attempted to explain away his actions. "I don't understand. I'm not committing fraud...My crime is the source of the money as a result of the drug trafficking."

Intermittent moments of jest in the court or breaks for lunch or reprieves followed with Guzmán exchanging long stares at his wife.

She reciprocated with beaming smiles and nods; at one point even mouthing some silent nothings.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

M.L. Nestel is a Newsweek senior writer. A native of Los Angeles, M.L. is one of a select few who ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.