On March 30, 1981, John W. Hinckley Jr., shot former President Ronald Reagan and three others outside the Washington Hilton in the nation's capital. After more than three decades in a government psychiatric prison, a federal judge in Washington on Wednesday granted a request for Hinckley to live with his mother in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Two weeks after the murder attempt, Newsweek profiled the then 25-year-old would-be assassin. The story below is excerpted from April 13, 1981 issue.

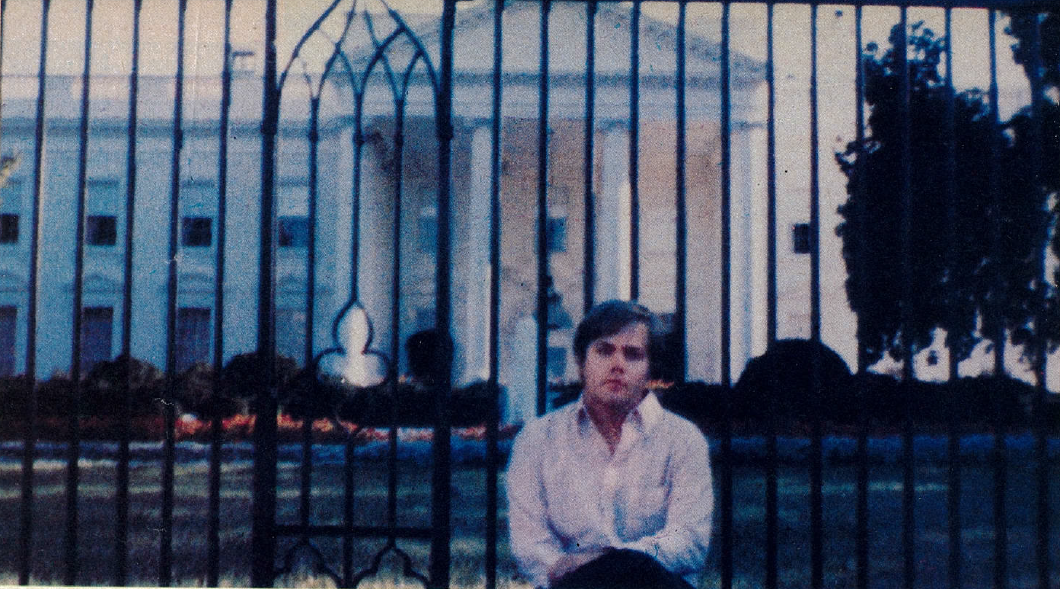

In a life empty of achievement, John Warnock Hinckley Jr. finally succeeded at something last week. He made an impression on Jodie Foster that will last a lifetime. Apparently alone, he conceived and carried out his grotesque declaration of love, a "historical deed" intended to bridge the gap between his lonely world of bus stations and seedy motels and her bustling life full of promise; a horrible act distantly rooted in an idea of chivalry, like a scrawled obscenity that started out as a love poem. It was the act of a loser—a 25-year-old drifter who thought that shooting the President would make an impressive introduction to the teen-age actress he had never met.

He led a life of almost willful failure and obscurity. Although at least average as a student, he spent seven years off and on at Texas Tech University and fell one semester short of earning a degree. He joined the National Socialist Party of America, and struck these jackbooted admirers of Hitler as dangerously unstable and potentially violent. Applying for work at a Colorado newspaper, he invented a job history for himself-as a bartender. He left behind few vivid impressions, and almost no favorable ones; some of the few words spoken in his behalf last week came from a maid at the rundown Denver-area motel where he lived for two weeks shortly before the assassination attempt. "He kept the room real neat," she recalled. "I never saw a liquor bottle or a beer can or any roaches."

He remained a nonentity even in crime; when he was picked up at the Nashville airport trying to board a plane while carrying three guns, the offense was considered too trivial for him to be fingerprinted.

Hinckley is largely self-made as a failure. He is the third and youngest child of a wealthy Denver oilman active in religious groups and respected in business. Hinckley's sister, Diane, 28, was an unusually popular and attractive girl who married a Dallas insurance executive; his brother, Scott, 30, is established in his father's business. Living in their shadow may have been part of John Hinckley's problem; a business acquaintance of his father recalled that he never spoke of his troubled younger son. "I never knew he had another son," said the colleague, Robert Kadane. "I thought he had only one boy." Yet just two weeks before the assassination attempt, Hinckley Sr. met with officers of one of his favorite charities—World Vision International, a Christian evangelical and humanitarian relief agency—and asked them to "pray for my son." His attitude was said to be one of "tremendous anxiety about the problem his son was having." The family retained Edward Bennett Williams's law firm to represent Hinckley after his arrest-but it was four days before they visited him in his cell in the Federal Correctional Institution in Butner, N.C.

Fatal Attraction: Somewhere in his wanderings Hinckley apparently crossed the invisible line into the same world inhabited by Mark David Chapman, the loner who came out of the night to kill John Lennon: a seductive world in which the lyrics of rock songs take on a personal meaning, and the faces in the movies seem to wink at you with a shared secret. From under a broadbrimmed hat, her blond hair falling in curls to her shoulders, Jodie Foster pouted fetchingly at Hinckley and won his heart. The tough-but-vulnerable, wise -but-innocent 12-year-old prostitute she portrayed in the 1976 film "Taxi Driver" had a fatal attraction for the lonely young man dreaming his life away over cheeseburgers and doughnuts in the low-rent district of Lubbock,

Texas—for whom real-life girlfriends were just one of the many kinds of friends he never made. Presumably, it did not escape his notice—and it certainly did not go unnoticed by the FBI last week—that the leading character of "Taxi Driver," played by Robert DeNiro, plots the assassination of a United States senator, and eventually becomes famous when he kills the young girl's pimp. And, NEWSWEEK has learned, the government has evidence indicating firmly hat Hinckley owned a copy of the book on which the movie was based.

Hinckley may have been touched by Iris, the young hooker, but unfortunately he fell in love with Foster, the real person. His problem may have worsened after Foster, with considerable fanfare, enrolled as a freshman at Yale last year. Hinckley had apparently spent some months in Hollywood back in 1976, but if he attempted to contact Foster then, there are no records of it. Any letters from him were buried among the thousands she receives each month, most thrown away unread. But suddenly her address was no longer in care of an agent or a studio, but a room in Welch Hall at Yale, more or less open to anyone who can pass as a college student. Driven by his obsession, Hinckley arrived in New Haven last fall only a few weeks after she did-and, ominously, just after he purchased two .22 handguns at a Texas pawnshop. Having come 2,000 miles from Lubbock, he spent much of his time a few blocks from her room, bragging at the Sheraton Park Plaza Hotel that he was Foster's boyfriend. Unkempt in his ratty Army jacket, he didn't look the part to bartender Mike Targove, and the newspaper and magazine pictures of Foster he pulled from his wallet weren't very convincing either. "The guy was ticking," Targove recalls.

How much closer he may have come to her is not known. In a Jetter recovered by the FBI from Hinckley's room in Washington, addressed to Foster but never mailed, he wrote, "Although we talked on the phone a couple of times, I never had the nerve to simply approach you and introduce myself." But Foster insists that she has "never met, spoken to, or in any way associated with" Hinckley.

Propriety: He apparently returned to New Haven at least once, in early March, when three notes were apparently slipped under her door. Among them was a commercial greeting card, in the contemporary-humorous vein, which began "I'm a person of few words," and then repeated "I love you" dozens of times. It was signed "John." Foster turned these over to her dean, and they are now in the possession of the FBI. But Hinckley never overstepped the boundaries of propriety; his impassioned final testament to his absurd love was as polite as it was crazy. "Besides my shyness," he wrote, "I honestly did not wish to bother YOU With my constant presence"-so he would kill the President as a less intrusive way to get her attention, "respect and Jove."

It's possible that he was not always so considerate of her. FBI agents have reopened their investigation of a stenciled Jetter they received last fall warning that an attempt would be made to kidnap Foster, for what were said to be romantic reasons rather than ransom. It was mailed from Denver, where Hinckley was living at the time. The whole experience has been a useful—if alarming—lesson for the young actress in "the power of films to direct people's lives." But a frightened and bewildered Foster wants only to return to the unglamorous life of a freshman. "It's not myself that's involved," she insists plaintively. "I'm not involved in any of this."

If there is a lesson in Hinckley's troubled life, it is an exceedingly elusive one. His downfall cannot be blamed on the wrong sorts of friends; he had none. Nor on a broken home; his parents' marriage was stable. As his father's oil- and gas-drilling business prospered he moved the family from Oklahoma to the attractive Dallas enclave of University Park, and then to the even more fashionable Highland Park, to a house with a pool and a curved drive on a street that may well be the second most prestigious address for hundreds of miles around. The 1980 report of the Vanderbilt Energy Corp.—named in honor of Hinckley's older brother's alma mater, Vanderbilt University-was memorable for two lines: a substantial increase in net profit to $805,000, and the advice of Hinckley's father in his letter to shareholders: "Commit to the Lord whatever you do, and your plans will succeed" (Proverbs 16:3).

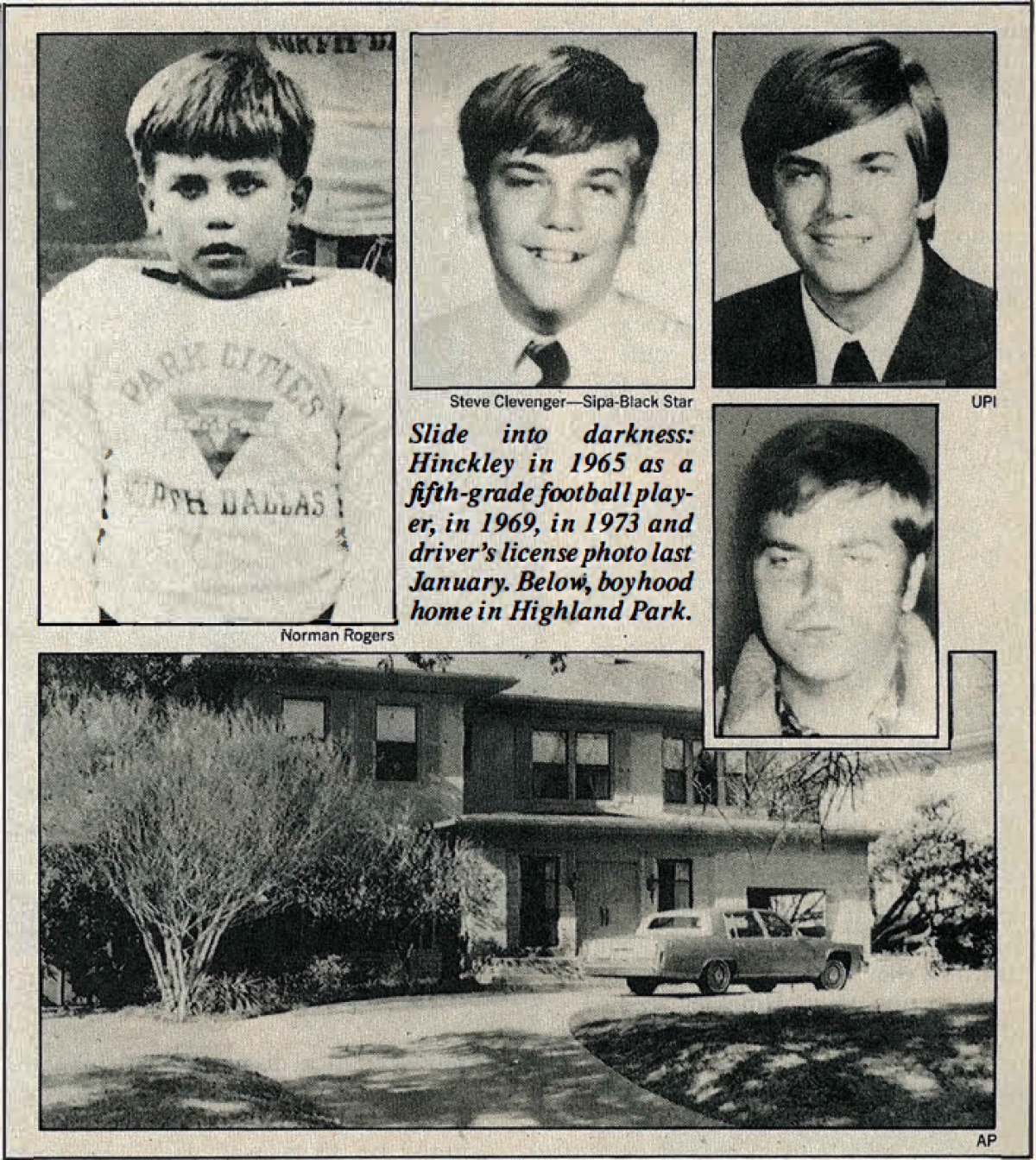

Conformity: In comfortable Highland Park, where the Hinckleys lived from 1966 until 1974, young John thrived at first. He was tall for his age, a good athlete and possessed of what classmate David Wildman called "good, natural looks—a big smile, a big set of teeth, blond hair, blue eyes." He was popular enough to be elected president of his homeroom class in seventh and eighth grades. Those are ages, of course, where conformity is valued, and he was well-endowed with that trait. Another former classmate recalls him fondly as "a pretty mellow guy, bland even."

Those were qualities that should have stood him in good stead in Highland Park High School, a bastion of oil-money privilege where the students are as uniform in their blond good looks as the blades of Astroturf in the school's football field. But he lacked the edge to compete in what is also one of the best public high schools in the nation; increasingly, he seemed to fade into the background. Academically, about in the middle. Athletically, nothing much. Socially, a nonentity. "It's tough not being wonderful in Highland Park," says former schoolmate Paul Gleiser. "He was a non-guy in high school." Most of his former classmates had to dig out their yearbooks last week to try and place Hinckley, and even with his bland, smiling picture at hand they could recall little about him. "He was just average," shrugs Kim Farrell. "An average sophomore, an average junior, an average senior. Average, average."

Probably to Hinckley's detriment, he was also the brother of a very much above average Highland Park student: his sister, Diane, three years older, an A student, homecoming queen nominee, a leader in the mixed choir and as vivacious and outgoing as her brother was reclusive. Even after she graduated, Hinckley was still thought of as "Diane's brother." That, of course, will no longer be true; as one sympathetic family friend observed last week, "For the rest of Diane's life, she'll be known as John Hinckley's sister."

Hinckley's slide into darkness seemed to pick up speed once he entered Texas Tech University in Lubbock, in the fall of 1973. "He wanted to go to Yale," says Becky Nugent, spokeswoman for the Highland Park schools. "But he apparently didn't have the grades to get in. So he had to go to Texas Tech instead." Academically, Texas Tech's reputation is modest, but its 23,000 students take pride in their parties. Hinckley was above average as a student, but his drinking and hell-raising were not up to Texas Tech standards. He sat out the beer-keg parties, and those who knew or suspected that he was the son of a wealthy Dallas family fretted that he was letting down his class. "You would have thought he'd be in a fraternity," said Charles Shanklin, manager of a campus haberdashery. "He had money, plenty of money. You'd've thought maybe he'd be an ATO (Alpha Tau Omega)."

Hinckley enrolled first in the College of Business Administration, then transferred to a liberal-arts program in 1975. He took a wide variety of courses, finally settling on English as a major by 1978. But by then his attendance had grown more and more sporadic. He was turning into one of those familiar, pathetic campus figures who make their college careers last most of their 20s, taking and dropping courses, reluctant to venture into the world-although what could have kept the friendless Hinckley in Lubbock is a mystery. During one of the interruptions in his education, he lived for a while in Hollywood, and sought work in a camera store, although he knew nothing of photography. In Lubbock, he is remembered as a glum, seedy figure in beltless blue jeans and a T shirt. "He was in a continual trudge," recalls one campus merchant. He survived on doughnuts and fast-food hamburgers, which he ate in his room, sometimes neglecting to throw out the wrappers. A superintendent who saw one of Hinckley's apartments remembers it as filled with empty

McDonald's sacks and not much else: "It didn't look like anybody lived there."

It was in this period that Hinckley had his brief and bizarre flirtation with the National Socialist Party of America. FBI agents have their doubts, but two high Nazi officials confirm that Hinckley joined the party in March 1978 when it was prominently in the news for plans to march through the largely Jewish community of Skokie, Ill. Hinckley's major contribution to American Nazism was made from a flatbed truck in St. Louis that same month, hurling racial invectives alongside Frank Colltn, then the party leader. But it had a profound effect on him, according to the current party chief, Michael Allen. "Before the [St. Louis] rally, he seemed like a pretty normal person," Allen says. "Outside of being a Nazi, he was a pretty ordinary fellow. But after the rally he was like a different person. He was very agitated. He said we needed something more dramatic [than rallies]. I took that to mean things like shooting people."

Letters: Hinckley confided some of these same ideas in about a dozen letters to Harold Covington, who was then a Nazi leader in North Carolina. Covington says that Hinckley was unhappy in Lubbock, and that he talked about moving to North Carolina. The Nazi leader is quick to note that "all of our discussion [about violence] was conducted on a purely theoretical plane. He didn't say let's go kill the President ... or anybody else." Nevertheless, Hinckley's attitude alarmed some of his Nazi superiors, and in November 1979, when Hinckley's membership was due to be renewed, the party apparently dropped him.

For an advocate of violence, Hinckley seems never to have gotten into a fist fight, or even raised his voice; as a would-be rabble-rouser he kept his opinions pretty much to himself. In a summer-session course in modem German history, he surpris_d his professor, Otto Nelson, by choosing to report on Hitler's long and turgid "Mein Kampf." But his three-page report was sober and factual, and earned an A-minus; Hinckley gave no hint that he ever considered putting Hitler's ideas into practice. If Hinckley was disappointed at leaving the Nazis, he also kept it to himself. But it was about that time that he began buying guns.

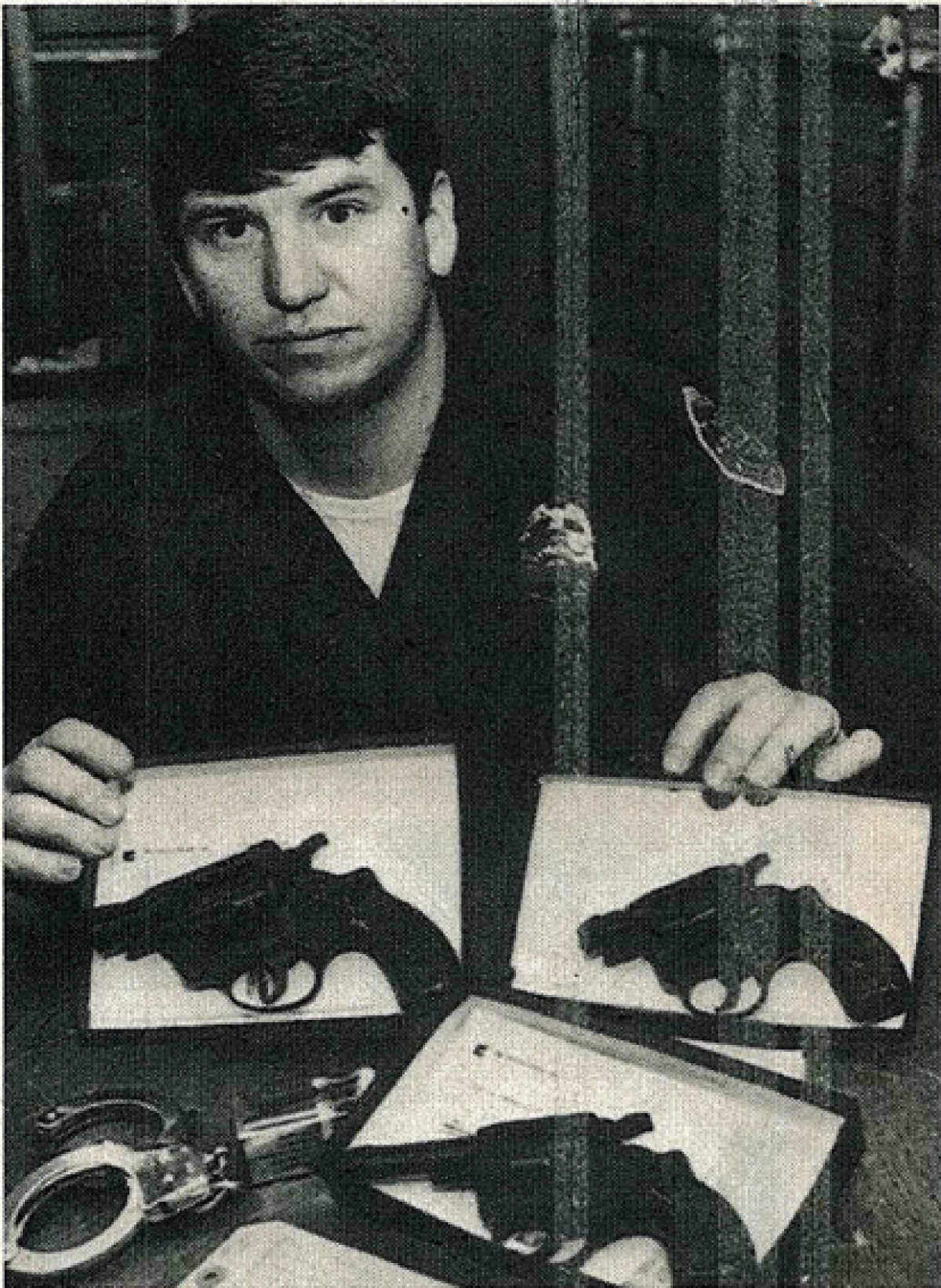

Up to this point, Hinckley seemed to strike most people as odd but not unhinged. But now things began to slip, faster. In February 1980, he sought help from a Lubbock physician, Dr. Baruch D. Rosen, for what may have been emotional problems. The doctor refused to say why Hinckley had sought him out. "Let's just say he had a problem," Rosen said. "I'm sure it will come out at the trial." Rosen treated him with the anti-depressant Surmontil and with 20 milligrams daily of Valium, a moderate dosage. Hinckley registered for a summer course at Texas Tech ("Anarchism, Fascism, Communism and Socialism"), but never showed qp at class. By late September, he was on his way to New Haven, Conn., to launch his fantasy courtship of Jodie Foster. He apparently stayed in New Haven only briefly; he turned up next in the Nashville, Tenn., airport, on the afternoon of Oct. 9, attempting to board a flight to New York carrying three handguns-two .22s and a .38. For the first time, Hinckley came to the attention of the law, but just barely-he paid a $50 cash bond that same afternoon, forfeited his guns and was on his way.

Four days later he was in Dallas, visiting a seedy downtown stretch of East Elm Street, where Rocky Goldstein sells weapons beneath a sign that advises "Guns don't cause crime any more than flies cause garbage." He replenished his arsenal with two inexpensive blue-steel .22-caliber Rohm revolvers with checkered stocks, assembled in Miami of West German parts. It was one of these guns that was recovered ,outside the Washington Hilton last week.

Hinckley spent little time in Lubbock last fall, although he was there long enough to have a political discussion with his apartment-house handyman; he reportedly expressed the opinion that all political leaders "should be done away with." He seems to have returned to his parents, who by this time were living in Evergreen, Colo., a wealthy suburb southwest of Denver. It was from here that FBI agents acting on a search warrant last week recovered three gun boxes, and Hinckley's diary, which contained everyday details of his mundane life—and a sheaf of news clippings on earlier assassinations. Hinckley's father reportedly told investigators he cut off his son's funds; he may have been receiving help from other family members. Hinckley applied for a job at Denver's two newspapers, giving references for jobs he had never held. He dabbled in the right-wing politics of the National Association of Constitutional Government, a self-proclaimed refuge for malcontents. "I'd like to say attract normal people," says the group's president, Henry Berriner, "but if we w, normal, we'd be the majority." And Jan. 21, he bought another gun, a .38.

A few Evergreen neighbors remember seeing Hinckley with girls, usually high school students. But mostly they remember him alone, wrapped in an oversize shat coat and watching the placid life of dov town Evergreen through sleepy, half-closed eyes. In March he made another pilgrimage to New Haven, and when he returned to Colorado he put up at the Golden Hours Motel, a run-down, $10.60-a-night hideaway on the highway west of Denver. traded a guitar and a portable typewri for $50 at G.I. Joe's Pawnshop, where the clerk, Brett Morris, remembers him looking "like any bum off the street but also "weird" and "scary." A lo policeman had the same reaction wl he spotted Hinckley standing in 1 motel parking lot and staring at 1 officer's patrol car; he question Hinckley but found no reason to h4 him. What he remembered later w, Hinckley's rose-tinted sunglasses-·· culiar equipment after dark-and eyes. "I never contacted a person nervous who didn't have something dirty on him," says the cop, Chris W sham. "He stands out as the most nervous person I've ever contacted."

Boyish: In those last few weeks before Hinckley left for Washington with his guns, he finally made a friend in Ginger Aucourt, the motel maid. Almost the only subject they had in common was the weather, but Aucourt and her teen-age daughter, Stacey, found his reticence endearing; he had, Ginger says, "a pleasant boyish face." Her opinion was unshaken even when Hinckley drove off on the morning of March 23, leaving a $64 bill unpaid. As investigators have retraced his journey, he headed in his white Plymouth Volare to his parents' house, and then to the airport, where he flew to Los Angeles by way of Salt Lake City. Then he doubled back east by bus, changing in Cleveland and Pittsburgh on the long ride to Washington.

He had given a pleasant little wave to Aucourt on his way out of the parking lot, and—uncharacteristically—he struck up an acquaintanceship with a fellow passenger on the three-day bus ride. The man who resisted friendships so long was at last allowing himself the luxury of human contact. His plans were still locked away in his heart, but perhaps he allowed just a glimmer of his happiness to show through. He was on his way at last; in just a few days, Jodie Foster would belong to him.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.