John Malkovich is very good at being bad. His Broadway breakthrough came in 1984 when, aged 31, he played the easygoing football lunk Biff in Death of a Salesman , and he's said that his favorite part was poor, tragic Lennie in Of Mice and Men (1992). But that's not what he's remembered for. Think of Malkovich and odds are, you'll picture his languid sexual predator Valmont, blot-ting Michelle Pfeiffer's innocence just for the hell of it in Dangerous Liaisons (1988), or Mitch Leary, wheedling and psychotic in In the Line of Fire (1993). Now, though, he's really getting into bad, the kind of bad that steps out of the movies and messes up real life: He's about to play a dictator.

Satur Diman Cha, a fictional combination of Saddam Hussein, Pol Pot and just about any other totalitarian you care to name, is the central character of Just Call Me God, a piece of what its writer-director, the Austrian Michael Sturminger, describes as music theater. It begins a European tour in Germany this March, and the plot is fairly simple: As his regime crumbles, a military dictator hides in a concert hall, where he is interviewed by a TV journalist. The action is accompanied live by music from an organ—what Sturminger calls "the dictator instrument, because it pretends it can do everything the other instruments can do."

The pair first conceived the idea in 2012, as a follow-up to two earlier collaborations that toured Europe: one, Malkovich's suggestion, about the Austrian serial killer Jack Unterweger; the other, Sturminger's, about serial seducer Casanova. (Good guys clearly don't appeal to them.) This may seem an odd way for a Hollywood star to spend his time, but there's a certain restlessness to Malkovich's creativity that expresses itself in unusual collaborations: a series of borderline- camp re-creations of famous portraits with the American photographer Sandro Miller; a film with Robert Rodriguez that won't be released for 100 years; designing a line of clothing sold in Italian stores. Though he now lives in Massachusetts, Malkovich and his wife spent six years living in France, and he speaks both French and Spanish. For an American, he's extremely European.

The script isn't quite finished yet. In fact, the pair were still working on it (Malkovich editing, Sturminger writing) during the U.S. presidential campaign; since then, power, its performance and its potential abuses have been much on everybody's mind. So when we meet, at a small and notably unshowy hotel in Munich, we begin by talking about how good actors are a little like dictators: They don't allow you to look at anyone else. Where does Malkovich feel an actor's power over his or her audience resides?

"I think it's generated from, as they say, Being There," he says. "In this space, at this time. To be where you are. If you don't have that, theater being purely ephemeral and organic, real power is very difficult to generate. It's a very difficult thing to fake. I mean, [actors] do fake it, but it's quite bad, really." He rolls the "r" on his "rilly''—rarely have two syllables sounded so dismissive.

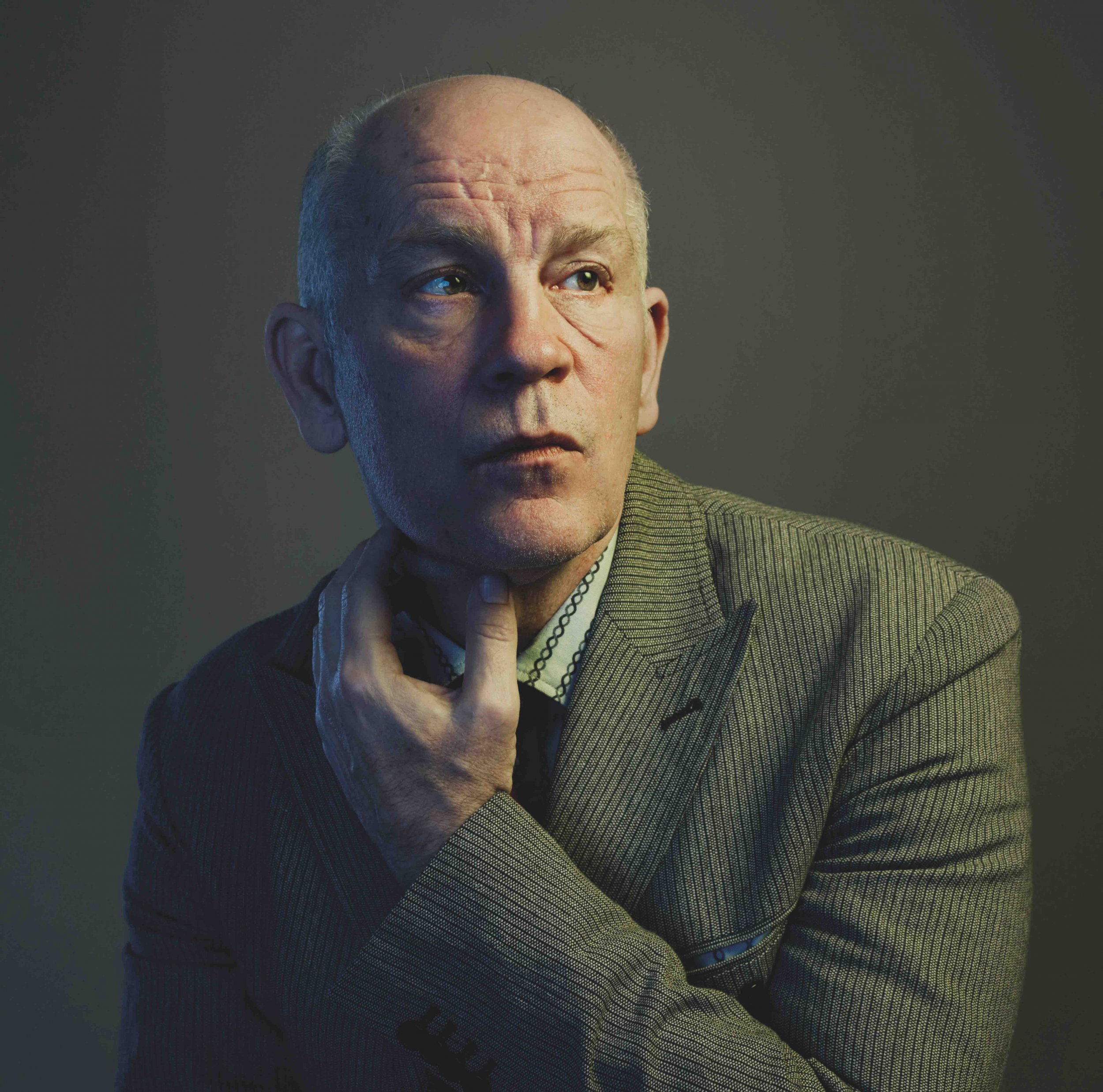

That's not to say Malkovich is rude; far from it, he is immensely polite, if a little de haut en bas. He sits on a small couch, elegant and slightly paunchy, with pointed ears, winding the end of his goatee beard between his fingers as he talks. His voice is a surprise: It's sometimes described as reedy, nearly always as drawling, but in fact it is a gentle bass, and he doesn't linger on his vowel sounds. What he does do is talk in clauses, with lengthy breaks in between: clause; pause; clause; pause. And then he hits a key word with a change of tone, bass to mezzo, and that light roll of his "r's." It makes his line of thought painless to follow; you glide along behind him. Part of his power as performer may be this: Malkovich is good at Being There, and he's good at taking you there with him.

What does it take for a performer to play bad? A favorite trick—used by dictators real and fictional—is invading other people's space. Forest Whitaker's Idi Amin ("Quite good," according to Malkovich) in The Last King of Scotland stands just slightly too close to his interlocutors. In The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin uses a raised arm as a way of making himself bigger, and of implying the fist might fall. But the best physical performance of evil Malkovich has seen was Anthony Hopkins as the media mogul Lambert Le Roux in Pravda , at the National Theatre in London in 1985.

"He was like a lizard or a snake being held back by an invisible leash," Malkovich says. "It was all forward and at a very precarious angle"—he holds his forearm in front of him at 45 degrees— "like he was going to launch into your face."

How will your dictator be? I ask. He isn't sure yet; it's too early in rehearsals, but he starts to tell me about a dinner he had in Paris the other night, with a woman friend and an Iranian businessman, "super, super smart, a manic depressive" who was in the high phase of his illness. "I don't think I spoke the entire evening; I was just watching his hands move," he says. "He had them almost in [my friend's] face, kind of like a snake charmer. Anyone watching would have thought it was aggressive, but it wasn't." He's excited, on the couch edge, spine completely straight, his right hand extended into my face, one finger curled. "I'll probably use some elements of that," he says, sitting back.

Malkovich has a reputation for being bad in real life as well as onstage. He told a student debating society that he'd be happy to see the left-wing British journalist Robert Fisk shot; he once chased and caught a would-be mugger in New York. But everything he says today about power and politics points to his being an instinctive libertarian: He sees politics as borderline immoral; taking away freedom of choice "is about as bad as you can do," and the worst abuse of power he can think of is sending people to war. "If I had a core belief," he says, "which I'm quite certain I don't, but if I had one, it'd be this: that the good never seek power. Never." If he had absolute power himself, he'd use it to encourage creativity and self-reliance, because he sees creativity as a kind of medicine for society, and, he says, his voice softening, "people can make such beautiful things."

There is just one moment when I get a taste of the dark side, when he gets on to French libel laws—he's currently engaged in a defamation case with the newspaper Le Monde —and how they apply (or rather, don't) to the French government. This is the other time when he scoots to the front of the couch. He leans forward over the coffee cups, fixing me with his eyes. "What do you want me to take from that?" he says, his upper lip drawn back from his teeth. His skull, and his ears, seem to become more pointed. "What would you like me to tell my children? What would you have me say? Vote, vote, vote? No thanks; I'm good." He stares at me, then sits back. I feel ever so slightly sick. "Would you like another coffee?" he asks.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.