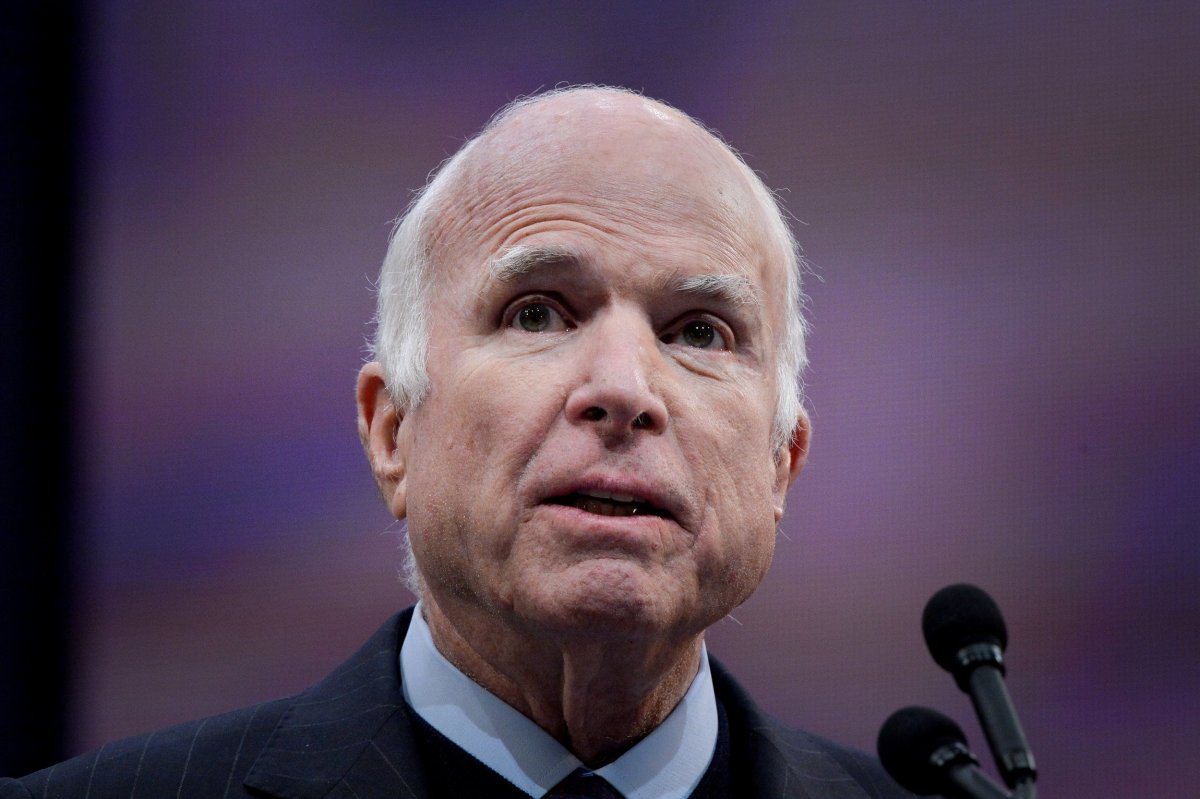

John McCain, United States senator and 2008 Republican nominee for president, has died at 81 following a lengthy and historic career in politics. He was diagnosed with brain cancer during the summer of 2017. Here's our 2008 cover story on the maverick senator and his long journey from a young 'rebel without a cause' to a leading presidential candidate.

During the 2000 election, Republican smear artists trying to stop the presidential campaign of John McCain spread rumors that the former POW was "nuts" because he had been "in the cage too long"—in the Hanoi Hilton for five and a half years. The campaign decided to make public Captain (now Senator) McCain's medical records, which showed that he had an enlarged prostate and trouble lifting his arms (repeatedly broken in captivity), but had been judged perfectly sane by a series of Navy psychiatrists who had tested him for years after his release from prison.

The details of those medical evaluations make you wonder why McCain is not stark raving mad today. Tortured repeatedly to extract a confession, McCain "tried to hang himself X2 to avoid giving in," reads the report of a psychiatrist at Jacksonville Naval Hospital in Florida who had interviewed McCain in 1973. "Broke three teeth as a result of rocks in diet," records another. Last week, as I read to McCain from these long-ago documents, he chimed in, "And also a fist in the face a couple of times." McCain was relaxing in a luxurious suite at the Beverly Hilton hotel in Los Angeles, having just received the endorsement of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (the two made an odd couple—the tanned, coifed, buff movie warrior and the pale, wispy-haired real one). His years in captivity were "terrible," McCain said, but, his voice gaining emphasis and urgency, he went on: "In some ways, it was the most magnificent time, because of the courage and bravery of those I had the privilege of serving with." He seemed to hear himself and quickly added: "Veterans really hate war. I hope there's no glorification of war in anything I've written or said."

But there is. How could he avoid glorifying war in a memoir called "Faith of My Fathers" about his grandfather, who commanded a carrier fleet against Japan in World War II, and his father, who was an ace sub commander in World War II and commander of Pacific forces in the Vietnam War? What he objects to, he later made clear in the interview with Newsweek, is "self-glory." The lesson from war he learned—the true faith of his fathers—is that there are "causes greater than self," like country and freedom, worth dying for.

The McCains are not like most Americans. They belong to a warrior caste that has been fighting America's conflicts for more than two centuries. (McCain's grandfather Adm. John S. McCain was depressed at the surrender of Japan. He complained to his chief of staff, "I feel lost. I don't know what to do," and died of a heart attack four days later.) The legacy and experience of war in some ways made John S. McCain III a truly humble man, capable of profound forgiveness—even for the jailers who abused him in Hanoi. But McCain's grace was hard won, and it is in a way a work in progress, a one-day-at-a-time struggle and balancing act. He is often funny, even devil-may-care, and at the same time a little sad. His temper lurks—controlled, but sometimes barely. I asked about a report that McCain's handlers need to caution him against blowing up during presidential debates. "No," he said. "They told me to appear presidential." McCain flashes a smile from time to time that is more like a smirk, "a defense mechanism—to smile, not appear angry or frustrated," he acknowledges. "I had to smile a lot last night," he adds, trying not to smirk. In a debate, his chief opponent, Mitt Romney, had tried to get his goat by raising doubts about McCain's conservative credentials and by accusing him of distorting his record.

McCain, who clearly cannot stand Romney (and vice versa), bridles at anyone or anything that impugns his honor, most sacred of military virtues. In rare weak moments, he can seem prickly, impetuous, vindictive—the sort of military martinet whose finger is supposed to be kept far from the button. Yet he is endowed with self-knowledge and self-effacing dignity. "I'm a man of many failings," McCain says with a genuine, if practiced, ruefulness. "I make no bones about it. That's why I'm such a believer in redemption. I've done many, many things wrong in my life. The key is to try to improve." There are a number of U.S. senators who can attest to McCain's repentance with handwritten apologies for his intemperance.

John McCain, 71, will be the oldest president ever elected if he goes on to win his party's nomination and the White House in November. He has made a long, hard journey from being a "rebel without a cause," as he described himself to one of those Navy psychiatrists back in the 1970s, to a man who aspires to lead the nation and the world. As an angry toddler, he would hold his breath until he passed out (his parents' cure was to drop him fully clothed into a bathtub of icy water). He has found transcendence, if not exactly peace, through duty and suffering that most people can barely imagine.

There is a telling line in "Faith of My Fathers": "I was on leave from the Navy when I attended high school." At Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Va., then a school for the sons of Southern gentry, McCain daydreamed of going to Princeton. He had been entranced by Princeton's lazy beauty and wanted to join an eating club with the other young gentlemen. But from birth, he had been marked for the U.S. Naval Academy. He responded by rebelling. According to Robert Timberg's "The Nightingale's Song," McCain's nicknames at EHS were "Punk," "Nasty" and "McNasty." A classmate described him as a "tough, mean little f–––er." Episcopal had borrowed from state military schools the sobriquet "rat" to describe first-year students at the mercy of upperclassmen hazing. McCain writes: "My resentment, along with my affected disregard for rules and school authorities, soon earned me the distinction of 'worst rat'." At Annapolis, he was, he writes, "a slob." He looked for authorities to subvert, settling on a bullying, second-year midshipman he and his friends dubbed "Sh–––y Witty the Middy," and making life miserable for a by-the-book captain who was supposed to discipline him. "I acted like a jerk," McCain writes. McCain came close to "bilging"—getting kicked out—but seemed to know exactly how far he could go. He graduated fifth from the bottom of his class.

Choosing naval aviation, he was at best an average pilot, a daredevil, "kick-the-tires and light-the-fire" type who sacrificed careful preparation for more time at the O Club bar. He wanted combat in Vietnam and got it. On his 23rd mission over North Vietnam, on Oct. 26, 1967, he was flying through heavy flak over Hanoi, dodging SAM missiles that looked "like flying telephone poles," when he heard a "beep" signaling that a SAM had locked on to his plane. McCain was just about to drop his bomb on target. He writes that he should have jinked to evade the missile, but out of stubbornness, or a mad kind of bravery, he flew straight on and toggled the bomb switch—just as the missile blew off the right wing of his plane. The force of the ejection from the spinning plane broke his right leg and both arms.

After he parachuted into a lake in the middle of Hanoi, a North Vietnamese guard shattered his shoulder with a rifle butt and plunged a bayonet into his ankle and groin. Near death, McCain survived in prison camp by sheer cussedness. The same belligerence that got him into trouble in school worked to maintain his spirits as he cursed and taunted his guards in solitary confinement. Yet he discovered that he could not make it alone. He began to drift off in terrible, dangerous reveries. "On several occasions, I became terribly annoyed when a guard entered my cell to take me to the bath or to bring me my food and disrupted some flight of fantasy," he writes. With regular beatings, the guards tried to break him and make him confess his sins as an "air pirate." Despairing, "fearing the close approach of my moment of dishonor," he climbed on his waste bucket and tried to hang himself by tying his shirt to a window shutter and wrapping it around his neck. Before he could kick the bucket, the guards stopped him. (He tried a second time, in a more halfhearted way; "I doubt I really intended to kill myself," he writes.) What saved McCain were his fellow prisoners. They communicated by tapping on the walls and pipes, and over time, as the brutality of the guards slowly let up, held religious services and plays (McCain was both chaplain and entertainment officer; he would act out movies he made up in his head). "To hold on to love and honor, I needed to be part of a fraternity," McCain writes. "I was not as strong a man as I had once believed myself to be."

McCain did make a meaningless confession of his "air piracy," and it haunted him to think his father would find out. Unbeknownst to McCain, his father had been elevated to become CINCPAC, the commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific, making McCain into what his jailers called a "Crown Prince." As a propaganda stunt, McCain was offered early release after about a year of captivity. He refused to leave before his comrades—and remained in prison for four more years. McCain sensed that he was getting "extra attention" from his guards (i.e., more beatings), but also that they did not want him to die or to return home gravely scarred. Always, the fear of disgracing his forebears hung over him. "He has been preoccupied with escaping the shadow of his father and establishing his own image and identity in the eyes of others," reads a psychiatric evaluation in McCain's medical files. "He feels his experiences and performance as a POW have finally permitted this to happen." Released after the 1973 Peace Accords, McCain returned to the United States a hero. "Felt fulfillment when his Dad was introduced at a dinner as 'Commander McCain's father.' He had arrived," noted the psychiatric report in 1974.

Like his father and grandfather, McCain wanted to be an admiral, but, too disabled to fly, he knew he would never command a carrier group, a prerequisite for winning four stars like the two older McCains. While working as a naval liaison officer with Congress in the late '70s, McCain discovered a flair for politics. He decided to run for the House. Remarried (his first marriage did not survive the strangeness and strain of repatriation) to a beer heiress, he used his new wife's family ties to win a safe seat in Arizona, and then essentially inherited Barry Goldwater's Senate seat in 1987.

In the military, there are two kinds of leaders, McCain mused in his interview with Newsweek—the "organizer of victory" type, like Gen. George Marshall and Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the more "inspirational" type, like his father and grandfather, who may not be terribly organized but are gifted at leading men into battle. Likewise, said McCain, there are different types of senators. "One is the person who is involved in the detail and the appropriation for the road or the bypass," he said—the type of lawmaker who gets involved in the "minutiae" that helps "people get re-elected." McCain said, unenthusiastically: "I respect that kind of senator." Then there is the "policymaking" senator, clearly McCain's model. He mentioned that on his way to work every day he passed the statue of the late Richard Russell, senator from Georgia, wise man confidant of Lyndon Johnson and all-powerful chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

McCain has many admirers among his colleagues. "I consider him a leader," says Sen. Susan Collins, Republican of Maine and a fellow member of the Armed Services Committee. "He has forged bipartisan coalitions on a lot of different issues, including global warming and campaign finance and the patient bill of rights and greenhouse-gas emissions. He's a real player in the Senate. He has tremendous impact, even when we're not on the same side. He is usually early on an issue and right on an issue." McCain does have a refreshing knack for reaching across the aisle. In 2004, he had a vodka-drinking contest with Hillary Clinton on a Senate junket to Estonia. Former Democratic majority leader Tom Daschle has written that he engaged in serious talks with McCain in 2001 to bring him over to the Democratic Party. "I was never going to leave my party, you ask anybody, I was one of the biggest campaigners for Republicans out there," McCain insists now. McCain is not a loner, but he is independent-minded. His staff is devoted; they call themselves "McCainiacs."

But a number of senators and former lawmakers are still licking their wounds from run-ins with McCain. "It's sad, really," says former senator Bob Smith of New Hampshire. "John McCain can tell a good joke and we can laugh, and I've had my share of good times with him." That is the side of McCain, says Smith, that the press sees. But behind the scenes lurks a less amiable McCain. "You can disagree without being disagreeable," says Smith. "And I don't think John is able to do that. If he disagrees with you, he does it in a way that is disagreeable."

The lore of "Senator Hothead," as McCain has been dubbed over the years, is considerable. McCain is widely reported to have yelled profanities at senators and even shoved one or two (including the late Strom Thurmond, a feisty nonagenarian at the time of the alleged incident). After McCain used an obscenity to describe Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa to his face in 1992, Grassley did not speak to McCain for more than a year. ("That's all water over the dam," Grassley says.) McCain has reportedly learned to control his temper; still, there are moments when he cannot or does not. Last spring, at a closed-door meeting of senators and staff, Sen. John Cornyn of Texas tried to amend the immigration bill to make ineligible convicted felons, known terrorists and gang members. Agitated that any attempt to amend the bill would jeopardize its slim chance of passage (ultimately, the bill failed), McCain snapped, "This is chickens–––." Cornyn shot back that McCain shouldn't come parachuting in off the presidential-campaign trail at the last minute and start making demands. "F––– you," said McCain, in front of about 30 witnesses. (A Cornyn aide says that the Texas senator was unbothered by the incident. "I think he just thought, 'Here's John being a jerk'," says the aide, who declined to be identified speaking for Cornyn.)

Sen. Thad Cochran, Republican of Mississippi, has had his share of dust-ups with McCain, usually over some appropriation that McCain regards as pork-barrel spending. "He gets very volatile," Cochran tells Newsweek. "He gets red in the face. He talks loud." Cochran, who says he is still a friend of McCain's ("at least on my part"), says the Senate dining room has lately been buzzing with Senator Hothead stories, mostly stirred by a recent wave of press interest. "I was surprised to find so many senators who'd had a personal experience when he'd lost his temper," says Cochran. Did he find McCain's temper to be somehow disabling or disqualifying in a potential president? "I don't know how to assess that," says Cochran. "I certainly know no other president since I've been here who's had a temperament like that. There's some who were capable of getting angry, of course. Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter both. But this …" His voice trailed away. "You like to think your president would be cool, calm and collected. He's commander in chief." (Cochran has endorsed Romney, who has sought to make McCain's temper a campaign issue.)

McCain acknowledged that he has had "strong disagreement with appropriators from time to time … of course I have." But he rattled off a list of senior Republicans who respect him, including Sen. John Warner of Virginia and former senator Trent Lott of Mississippi. "You don't get the support of these people if they don't respect you," he said. "That's really what the Senate is about, not friendship." As for his anger, he asks, steam rising, "Was I angry when I saw the abuse [convicted-felon lobbyist Jack] Abramoff committed and his friends and members of Congress? Of course I was." McCain has long had chilly relations with conservative activists in Washington, D.C., including Grover Norquist, an advocate of tax cutting who is close to many right-of-center lobbyists. "McCain reacts poorly when criticized," says Norquist. "When the NRA and the right-to-life and right-to-work groups criticized him, he reacted like they were personal attacks, and then he supported some gun-control legislation to get back at the NRA." Norquist denies that he has ever personally tangled with McCain, though Norquist was subpoenaed to testify when McCain's Indian Affairs Committee looked into charges that Abramoff (a friend and sometime business partner of Norquist's) was fleecing Native American groups applying for gambling licenses. "Some of his staff guys took a whack at me," says Norquist. "No harm, no foul."

If McCain does not suffer fools lightly, that is because they are doing foolish things to the national interest, says Collins of Maine. "I have never seen him lose control of himself," she says. "What I have seen is him being justifiably angry, even very angry, at behavior that was corrupt or spending that was absurd." Sen. Joe Lieberman tells Newsweek: "John is a remarkably disciplined person, including emotionally. Have I seen him passionate about things? Sure. But this is not a kind of anger that loses control; this is a passion about stuff." Sen. Richard Shelby recalled a typical McCain blow-up when Shelby, an Alabama Republican, tried to slip $1.5 million in the 2001 Interior Department Appropriation Bill to help pay for the restoration of Birmingham's 56-foot-tall cast-iron statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and forge.

Once McCain smells corruption, he does not let go. When he began investigating Boeing for what he regarded as a sweetheart deal with the Air Force to lease tankers, it turned out that Boeing had broken the law by hiring a former Air Force procurement officer who had worked on the tanker contract. McCain relentlessly badgered the Pentagon, holding up Air Force promotions until the Defense Department produced some allegedly inculpatory e-mails. The Pentagon balked and McCain wound up in the office of the then Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, yelling at the top of his lungs, say a Pentagon official and an adviser to Rumsfeld who declined to be identified discussing a confidential meeting. McCain seemed to believe that Rumsfeld had impugned his patriotism, an unpardonable insult in McCain's world view. Mark Salter, a longtime adviser, denies the incident happened. "He never yelled at Rumsfeld," says Salter. "He bruised him up in committee hearings, but he never yelled at him."

McCain may have a bit of a vindictive streak. "John has an enemies list longer than Nixon's," says a former Pentagon official who did not want to get on it. "And, unlike Nixon, McCain really does try to get you." After the Boeing scandal, three Air Force officials who quit all found that one of McCain's top aides had quietly spread word around the defense community that anyone hiring them would risk the senator's displeasure. And he still has an impetuosity that is nervous-making to old foreign-policy hands. One of them, a former high official in several Republican administrations who occasionally advises McCain (and wishes to continue to) worries to Newsweek about McCain's "quirky" judgment and his unwillingness to change his mind once it's made up.

McCain will trim his sails politically when necessary, but he is obviously dispirited by anything that smacks of pandering. A year ago he was the front runner, claiming the mantle of the Republican establishment and hoping to inherit the Bush fund-raising machine. But when his fund-raising stalled, he dumped some of his top campaign staff and wound up in the role of maverick once again, pushing from the outside. McCain claims that staff shake-ups are nothing new to presidential campaigns (true) and that he lost support among conservatives because he favored a compromise on immigration. In early 2007, when some of his advisers tried to get him to soften his stances on immigration and Iraq, he snapped, "Don't try to change my mind," says a former aide who wished to avoid McCain's wrath by remaining anonymous.

It was a characteristically principled stand, and yet McCain's leadership skills are called into question by the near meltdown of his campaign. "Nobody knew who the boss was," says one of McCain's longtime friends and advisers, who declined to be named discussing the internal workings of the campaign. "You couldn't get people to return your calls. It was bad." More troubling, says this associate, was McCain's blind eye to the problem. "He didn't really seem to want to deal with it."

Last summer McCain told Newsweek that he was "never quite comfortable being the front runner, per se." A half a year later, having passed the true test of winning the Republicans-only primary in Florida, he is once again the front runner. "Whoops! Trouble!" cackled McCain last week as he mordantly contemplated prosperity. The campaign cash is flowing in again; he and his aides joked about no more cheap motels as they enjoyed the plush surroundings of their Beverly Hills hotel suite. McCain, who never attained the stars and bars worn by his father and grandfather, has a real chance to become commander in chief. He will no doubt do everything in his power to keep the faith of his fathers. It will be a struggle. It always has been.

This article originally appeared in the February 11, 2008 issue of Newsweek, with the headline "What These Eyes Have Seen."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.