When Mitt Romney declared, during a Republican primary debate in Tampa, that he would pressure illegal immigrants to "self-deport" back to their home countries, John McCain was downright disturbed. Worried that his former rival was grievously wounding himself with Hispanic voters, the Arizona senator staged an intervention. He and fellow senator Lindsey Graham placed a joint call to Romney in January, urging him to tone down his rhetoric. Romney listened politely, sources say, and did not use the phrase again.

It was a rare instance of Romney taking counsel from the man who beat him in the last campaign—and who has been relegated to a behind-the-scenes role in this one. Four years after his own presidential bid, McCain's luster as a Republican Party spokesman appears to have dimmed: a number of proposed campaign trips on Romney's behalf have quietly evaporated, and there has been no offer of a speaking slot at the GOP convention. "He's chomping at the bit to do something," a McCain aide confides.

Romney, to be sure, has been willing to use McCain when it suits him. The candidate's strategists have asked him to do fundraising events in places like Annapolis, Md., and Pensacola, Fla., where he is popular among military families. But such events take place far from the television cameras. "If you're the Republican nominee, the campaign is about the future," says Steve Schmidt, who oversaw McCain's 2008 effort. "John McCain is very much a figure of the immediate past."

Right after losing in 2000, McCain went to Tahiti, where he would hang around the hotel desk waiting for a one-page sheet of news to come in. "I almost went crazy," he recalls. "You're all geared up. You can't come to a full stop."

Having once delighted in working with Democrats, McCain might have emerged as a dealmaker during the Obama era. But there were two problems. First, McCain had to embrace a harder-edged conservatism to survive a primary challenge in Arizona. "He understood the party was in rebellion and he'd have to move substantially to the right," says a former lieutenant.

The other glitch was his strikingly antagonistic relationship with Obama. Despite a fence-mending meeting at the White House last year, the president never called again. McCain contrasts Obama's aloof approach to lawmakers with that of Bill Clinton, who "was remarkably good to me." In fact, McCain told me that he and Clinton chatted about policy in occasional phone calls during his 2008 campaign, even as the former president was backing Obama.

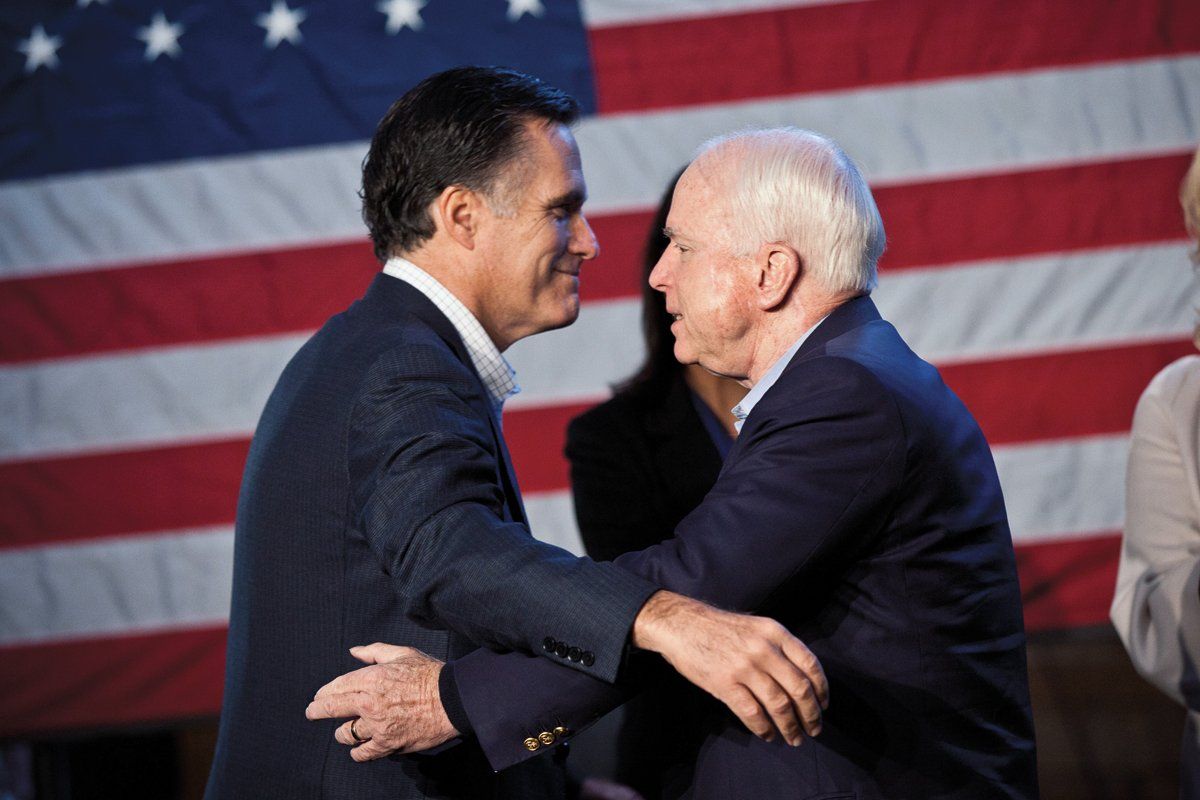

As for McCain's relationship with Romney, it seems to have improved—-somewhat—since 2008. The wounds sustained during their primary battle had been unusually deep and personal: When Romney charged him with promoting amnesty for illegal immigrants, McCain accused his rival of "desperate, flailing, and false attacks." And at one point, Romney ripped McCain for "Nixon-era" tactics. But once the battle ended, says McCain, "nobody helped me more than Mitt Romney." The vanquished candidate visited McCain's retreat in Sedona "and we became friends. I wouldn't say close friends. Why look back in anger? It's not healthy for you mentally."

The Romney camp has made similarly conciliatory noises. Stuart Stevens, Romney's top strategist, told me that McCain is "a tremendous asset." But if that's the case, why has he been so underutilized on the campaign trail?

One reason may be McCain's tendency to commit candor. The senator caused a stir when he recently told reporters that his decision to bypass Romney as the VP pick in 2008 had nothing to do with his tax returns; it was, he said, that "Sarah Palin was the better candidate." (McCain told me that he didn't mean the remark as a dig at Romney—and added that complaining about out-of-context headlines "is just stupid and a waste of time.") Then, days after the Palin flap, McCain launched a stinging assault on GOP congress-woman Michele Bachmann for questioning whether Hillary Clinton aide Huma Abedin had ties through family members to the Muslim Brotherhood. Bachmann's accusations, McCain told me, are "just terribly wrong ... It's McCarthyism."

But the bigger problem may be that Romney—and the Republican Party -itself—has moved to a very different ideological place than McCain has. The senator is careful not to betray any hint of dissatisfaction with Romney. "He asks me for advice and we have good conversations. He certainly listens to me," McCain says. Yet there is mounting evidence that his suggestions are incompatible with the image Romney is trying to project.

McCain says that Romney supports the Simpson-Bowles budget plan "as a blueprint"—but the proposal includes tax increases, and Romney is talking about slashing corporate tax rates instead. And, even though Romney took McCain's advice on the phrase "self-deport," he has remained further to the right on immigration than the senator would like. "He gets 24 percent of the Hispanic vote," McCain told me. "They need to do more outreach."

McCain's greatest strength is as a leader on foreign affairs, Schmidt says, but that is the issue on which his differences with Romney may be the starkest. "He has not got a lot of instincts on some of these -national-security issues, but he has the right instincts," McCain says. Yet the candidate rarely brings up the muddled mess in Afghanistan; nor has he embraced McCain's call for U.S. airstrikes to support the rebels in Syria. "We all know it's not popular, including with the Ron Paul wing of our party," McCain admits.

It's little surprise, then, that Team Romney doesn't want to give McCain a high-profile surrogate role—and be stuck defending his pronouncements on military intervention. "Do they want to own McCain on foreign policy?" one of the senator's confidants asks. "McCain is never a talking-points guy, and for a cautious campaign, that can be kind of a nightmare."

There may be one more reason for Romney's reluctance to involve McCain: both politicians are, at heart, men of moderation who had to suppress those instincts to appease the party's conservative power brokers. McCain's presence on the trail might serve as a nagging reminder that neither candidate was the right wing's choice for the nomination.

For the moment, McCain is something of a caged lion, circling his circumscribed world, using vacation breaks to jet off to foreign-policy hotspots. Early this month, McCain was in Tripoli, where he watched 200,000 flag-waving people pour into the streets to cheer Libya's first democratic election in four decades. Many approached him, some wearing T-shirts bearing pictures of slain relatives, to thank him for his push for U.S. airstrikes against Muammar Gaddafi's regime. "John likes a good fight," says his Senate pal Joe Lieberman. "He likes being in the arena."

But the domestic arena has drastically changed, and McCain bears part of the responsibility. It was his gamble with Palin—they still stay in touch—that helped unleash the hard-right tide that swept moderates and traditional conservatives from Capitol Hill, and turned the Republican primaries into a panderfest.

McCain resists the notion that the GOP has been captured by Tea Party types who have little use for him. "If the party had been taken over by that, Mitt wouldn't be the nominee," he says. Yet he also points out that, with the Supreme Court unraveling his beloved campaign-finance reform, the party is today "less relevant," much of its power having been lost to super PACs. "Now that we have Citizens United," he says, "nobody has to go to the Republican Party for money. You go to Sheldon Adelson, you go to Karl Rove." Which may help explain why John McCain is looking on from the shadows.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that McCain went to Tahiti after the 2008 campaign.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.