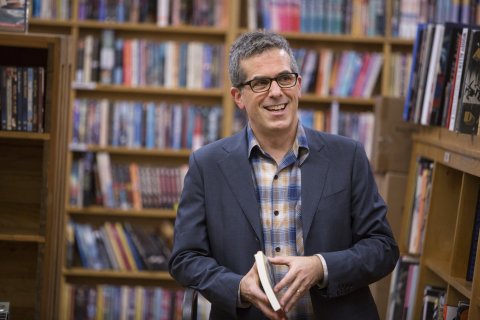

"I feel like Ray Liotta at the end of Goodfellas," the novelist Jonathan Lethem confided as we sat one recent evening at Henry's Pub in Berkeley, California, which was booming with World Series cheer. This alarming allusion to the Martin Scorsese Mafia movie—with its main character forced into a covert existence after becoming a government witness—had nothing to do, as far as I could tell, with unsavory associates from Lethem's childhood days in Brooklyn, New York, which he mined for popular novels like Motherless Brooklyn and The Fortress of Solitude.

Nor was he concerned that his most recent novel, A Gambler's Anatomy, might provoke backgammon's most ardent fans with its not-always-flattering depiction of high rollers. "How terrified can one be of the backgammon community?" he wondered. Not much, probably. And considering how rarely backgammon trends on Twitter, that community might well embrace Lethem for endowing the game with sex appeal.

No, the reference to Liotta's character living in some anonymous American town had only to do with Lethem's current residence in the comfortably sleepy Los Angeles suburb of Claremont, where he moved in 2010 to teach writing at Pomona College. For the past six years, the onetime literary ambassador of brownstone Brooklyn has occupied the Roy Edward Disney professorship of creative writing, a prestigious appointment that has consigned him to the eastern edge of Los Angeles County, on the cusp of the vast Inland Empire, which seems to intrigue him far more than the world-class city a few miles west on the I-10.

Lethem was appointed the Disney chair because its previous occupant, David Foster Wallace, committed suicide in 2008. "I became a collector of Wallace stories," Lethem told me of his arrival at Pomona, fraught as that was with grief for his predecessor. He recalled finding stains on his office furniture, the lingering traces of Wallace's tobacco-chewing habit.

As in Goodfellas, the move to the suburbs also represented a renunciation. Shortly after arriving in California, Lethem gave an interview to the Los Angeles Times in which he said Brooklyn had become "cancerous with novelists." In that interview, he declared New York no longer "the best place to write. The mental traffic level is very high there." He said he regrets the choice of words, but not the sentiment they pointed to, a feeling that Brooklyn has become too...Brooklyn. "It's soaked in glamour and money," he said of the Boerum Hill neighborhood where he grew up and set The Fortress of Solitude.

Having broken up with Brooklyn, Lethem set his next novel, 2013's Dissident Gardens, in Queens. The work did not suffer from a Brooklyn depletion, at least not in my opinion: I called it that year's best novel in The New Republic. Others also saw a maturation, lyrical writing finally married to a seriousness of theme. In The New York Times, Janet Maslin compared him to Philip Roth. His earlier novels had toyed with the conventions of science fiction and noir. This one went for something deeper, truer.

While Roth liked to stay close to Newark, Lethem has shown more of a propensity to explore. A Gambler's Anatomy, Lethem's new novel, is set even farther afield from Dean Street than its predecessor: Berlin, Singapore and, for most of the second half of the novel, the grungy streets around the University of California, Berkeley, the hometown of backgammon virtuoso Alexander Bruno, who returns to the Bay Area to have a giant tumor removed from behind his face. Robbed of his backgammon hustle, Bruno is a wingless bird, plummeting toward a hometown to which he'd hoped to never return.

Lethem novels now engender rock-star adulation but also the kind of critical scrutiny a mature artist can rightly expect. Ron Charles, in The Washington Post, complained that the Berkeley section of the novel was "tedious," though I found Lethem's evocation of a place struggling with its waning liberalism compelling. Kurt Andersen lauded the novel on the front cover of The New York Times Book Review, calling it both a "page-turner" and a "first-rate novel."

The novel's centerpiece is a 20-page narration of a 14-hour surgery at the hands of the iconoclastic surgeon Noah Behringer, who likes to perform his craft while listening to Jimi Hendrix and engaging in what Donald Trump might call "locker room talk."

For hours Behringer had borne down, into the paranasal and maxillary trenches, the nasopharynx, the orbital cavities, and into the tumor itself, the entrances he'd carved through its mass. His sense of scale was demolished. His tools and materials, the bipolar cautery and facial nerve stimulator, the tiny copper spoons and cup forceps and scissors, the neurosurgical Cottonoids, appeared like massive construction devices, excavators and steam shovels, brinked on shattered canyons of organ and tumor.

Lethem was an expert in neither professional backgammon nor maxillofacial oncology when he started work on A Gambler's Anatomy three years ago. He'd thought of making his protagonist a high-stakes poker player, but that had been relegated to the realm of cliché at least since James Bond asked for a shaken-not-stirred martini in Dr. No. Besides, someone he'd known as a kid in Brooklyn had become a backgammon player in East Asia, providing some grounding in reality. Lethem learned the game by reading its "sacred texts of strategy" and playing online, becoming fluent enough to incorporate backgammon lingo artfully into the novel. "I'm not sure I've ever before read a love scene that begins with a woman crying out, 'Double me, gammon me,'" Dwight Garner wrote in The New York Times. For the virtuoso Behringer performance, Lethem immersed himself in neurosurgery texts.

The streets of Berkeley were easier to summon. Lethem moved there after leaving Bennington College in Vermont, hitchhiking across the country to California. In Berkeley, Lethem said, he found "a residual trace" of the liberalism his parents had sought in pre-gentrified Brooklyn. He lived in the poorer flatlands of the city, not far from the onetime home of Philip K. Dick. Lethem laughed as he remembered sending out stories to obscure science-fiction magazines, just as his idol once had.

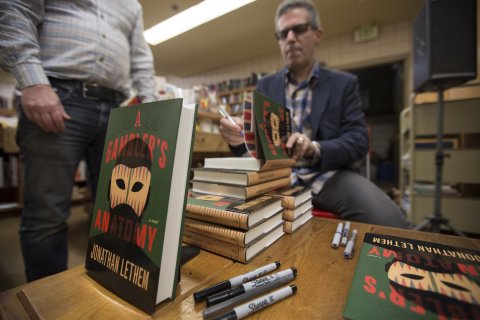

He also worked at the legendary Moe's Books, near the Berkeley campus. Shortly after we met at Henry's, Lethem was headed back there, this time to read from his latest novel. He recalled, as his audience filled rows of fold-out chairs, that it was Malcolm Jones's ebullient 1994 Newsweek review of Lethem's debut, Gun, With Occasional Music, that allowed him to pursue the writer's life. Motherless Brooklyn came five years later, Fortress of Solitude four years after that. The kinds of people who read and write book blogs began to talk of Lethem as one of the "literary Jonathans," along with Foer and Franzen. It's a silly grouping but also evidence that Lethem had arrived.

In keeping with his newfound Cali-phoria, Lethem told me of "not wanting to bring the New York baggage into play this time," thus situating Bruno in Berkeley, not the borough of Lethem's youth. And yet Berkeley has much the same function as Dean Street did in The Fortress of Solitude and the planned community of Sunnyside Gardens in Dissident Gardens, a place where adults are always ruining the idealistic fantasies of children. Lethem said he is fascinated by the "temporary utopia." The term seems paradoxical: What good is a utopia that doesn't last? If only temporary, it is a pleasant dream from which one wakes into reality's persistent squalor.

Berkeley was once a utopia—but not for Alexander Bruno. He had grown up poor, his mother joining the ranks of that city's intractable homeless population. A childhood friend, Keith Stolarsky, has become a wealthy landlord, one who has about as much use for the love-and-peace Berkeley of lore as the Koch Brothers. Bruno's surgery is successful, but he has to wear a mask as he wanders around Berkeley. His own identity is in question; so is that of this quintessentially American city that seems to wear plenty of masks.

Lethem told me that an "abiding interest in superficiality" drove him to write A Gambler's Anatomy, which frequently returns to the difference between the real self and the masked one, the poker face and the one behind it, plagued by a potentially fatal growth. You are one thing, then another. There is now an Equinox gym just a few blocks from where Berkeley students vowed, 50 years ago, to overthrow the capitalist regime.

It was nearly time for Lethem to read. We left Henry's and walked toward Moe's, the streets around the Berkeley campus thrumming with students. We stopped at a greasy spoon that figures into the novel, and Lethem pointed out some other relevant spots that have a role in A Gambler's Anatomy. Among these is People's Park, created in 1969 after then-Governor Ronald Reagan dispatched the National Guard to silence the radicals who'd claimed the land in the public's name.

People's Park is another perfect little Lethem utopia. Its name is aspirational, its founding a high watermark of 1960s radicalism. And yet, today, it is little more than a barren homeless encampment, a park frequented by people who have nowhere else to go.

Near the end of A Gambler's Anatomy, Berkeley undergoes a fresh paroxysm of pseudo-revolutionary violence, instigated by Bruno against his old friend, the landlord Stolarsky. Once again, People's Park is the scene of a pitched battle with police. Bruno escapes the violence and leaves Berkeley, swapping identities—which is to say, masks—once again. The last we see him, he is in Singapore, back to playing backgammon, striving to "learn the only important thing about most men: what cards they held."